Blog Archives

As If Heaven Had Ordained It

“Not one word of all the good promises that the Lord had made to the house of Israel had failed; all came to pass.” – Joshua 21:45

When the Continental Congress gathered in Philadelphia in 1774 to unite against the British, they decided to open their proceedings in scripture and prayer. An Episcopalian minister named Jacob Duché was chosen. Before his prayer, rumors arrived that the British had attacked Boston. A frightened and receptive audience awaited as Duché read Psalms 35:1: “Contend, O LORD, with those who contend with me; fight against those who fight against me!” It was the assigned reading for the day in the Episcopal lectionary, but John Adams says members of the Continental Congress were stunned when they heard the words. Adams wrote, “It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that psalm to be read on that morning.” Have you had such an experience where the scripture seemed perfect for what you were going through at the time? I have several such scriptures marked in my Bible. Once when I was anxious about a situation at work, I read Psalm 34:4, “I sought the LORD, and he answered me and delivered me from all my fears.” That verse gave me sudden comfort. Eventually, everything worked out. Another verse that has helped me when facing a difficult decision is the promise of James 1:5, “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given him.” Praying over that promise, God has given me direction time after time. Once when I was a hospital chaplain, I visited a patient writhing in pain, asking me to pray. As I was about to pray, two nurses entered and gave her tablets to take for pain, then left the room. Immediately I began to pray, and I sensed God telling me to quote Psalm 23, so I did. Even before I finished the psalm, she grew peaceful and still. I finished quoting the psalm, added a few more words asking God for healing, and then I looked up. The patient was resting. Her sister-in-law looked at me, eyes wide in amazement. I said, “That pain medicine hasn’t had time to work, has it?” The sister-in-law said, “No, but Psalm 23 did!” What scripture has given you guidance, comfort, or strength “as if Heaven had ordained” it?

Prayer

Lord, my heart is full of anxieties and desires, but your word is full of good promises and timely guidance. As I read scripture, show me how it applies to my life as if Heaven had ordained it for this day.

Book review: “Crusaders” by Dan Jones

Dan Jones. Crusaders: The Epic History of the Wars for the Holy Lands. Viking, 2019.

I have read several books on the Crusades, but this is the best I’ve read so far. Dan Jones has written numerous books on the Europeans in the Middle Ages, so this is his area of expertise. His work is thoroughly researched, but he also writes in an engaging style, opening most chapters with vignettes about colorful personalities, and he peppers the book with fascinating quotes and interesting details.

The title Crusaders (instead of “Crusades”) is deliberate, because, as Jones explains in his preface, he focuses on the personalities like Richard the Lionheart, telling stories of the combatants (mostly Christian, but he also gives coverage to prominent Muslim warriors, including a chapter on Saladin). Yet he tells the story in chronological order, which helps the reader to follow the facts.

With so much blood and horrendous violence, Jones could easily depict the Crusaders as pure evil, but as a good historian he leaves it to the reader to make moral judgments, even reminding the reader at times that as bad as the violence was, it was normal for all sides at that time in history. He simply tells the facts and quotes the sources that describe the characters, whether evil or holy, or, as many were, a mixture of both. The book truly helps the reader understand the reasons why the Crusades happened as they did by helping the reader understand life in the Middle Ages. Until I read this book, I didn’t fully understand why the Fourth Crusaders plundered Constantinople instead of invading Muslim territory, but now I understand the economic motivations of the Venetians.

The old adages about history repeating itself and not learning lessons from history are evident in these stories. One example is the defeat of the Fifth Crusade on the Nile River because they didn’t consider the geography of when the Nile would flood and stop their advance. Another example was how Emperor Frederick II was able to gain more by negotiation than the previous Crusaders had gained by war, because he spoke Arabic and was able to gain their trust.

Jones explains that the Crusades included the “Reconquista,” the seven hundred years of battles for Spain to retake the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims, which finally ended in 1492. Thus, instead of seeing the Crusades as a total failure, since the Crusaders were expelled from the Holy Land after the fall of Acre in 1291, he sees the battle for Spain as a success for the crusaders. He even cities numerous occasions when crusaders on their way to the Holy Land would stop off in Spain and help them win a battle, then sail on for Jerusalem. The author explains how, even as Europe lost interest in raising large international armies to fight Muslims in the Holy Land, the crusading spirit continued and degenerated into hunting down heretics in southern France, fighting pagan tribes in the Balkans, and even papal battles against Christian rulers who refused to submit to the pope.

I wish that Jones had explained more of the results of the Crusades. He does allude to how it gave power to the pope, and he ends the book by explaining the anti-Christian bitterness that remains among Muslims in the Middle East. He could have said more about how it affected Muslim treatment of Christian minorities in the Middle East, and how the contact opened doors of economic, cultural, and intellectual trade between East and West, even helping bring Arabic numerals and Aristotle’s philosophy to the West.

Sadly, Jones points out that the Crusades never fully ended, as Osama bin Laden referred to President George W. Bush as “the Chief Crusader… under the banner of the cross.” As ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi said, “the battle of Islam and its people against the crusaders and their followers is a long battle.”

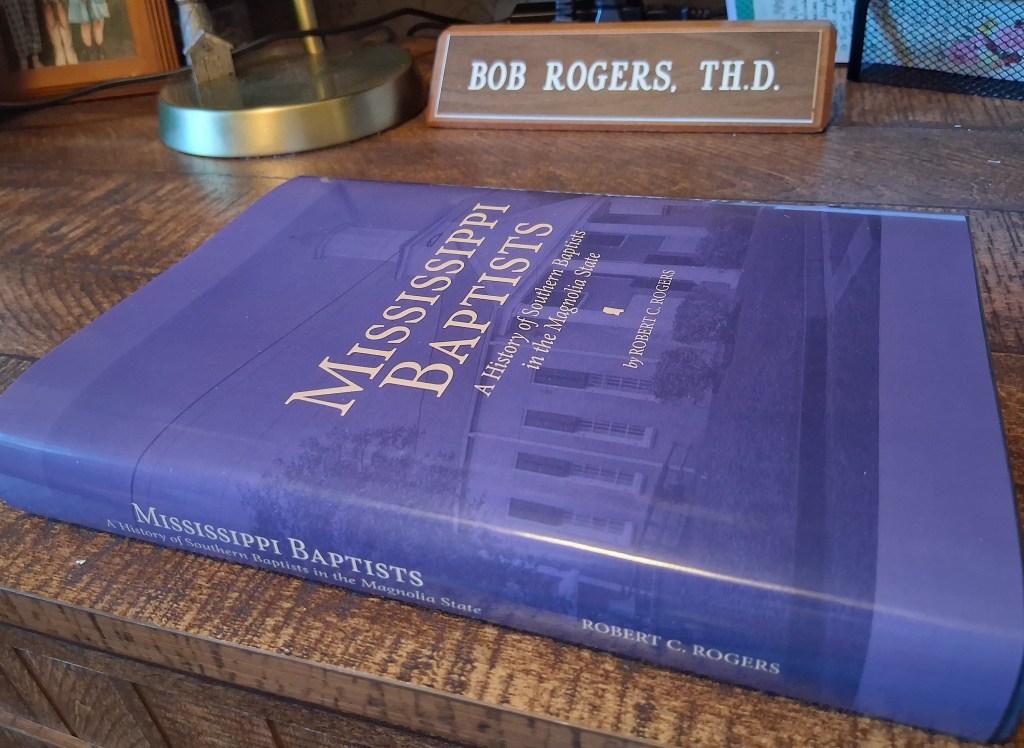

My new Miss. Baptist history book is now available!

My new book, Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, has been published by the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, and is now available to the public. It is a hardback book, 300 pages of text, plus four appendices, notes, and an index in the back.

In 2021, I signed a contract with the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board and Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission to revise and update R.A. McLemore’s book published in 1971, A History of Mississippi Baptists. While the new work is based on McLemore’s history, it has many more new features than simply the addition of a half century of recent history. I have included new research from the beginning. For example, I discovered evidence that the mother church of Mississippi Baptists was Ebenezer Baptist Church, Florence, South Carolina. Other new research includes the declaration of religious liberty by Richard Curtis, Jr., the first Baptist pastor in Mississippi; social and cultural information on typical Baptist life during different time periods; trends in Baptist theology; and details of the previously untold story of the McCall controversy of 1948-49. Throughout the book, I sought to write in a narrative style, including anecdotes that reflected the flavor of Baptist life.

You can get a book by making a donation to the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission at the link below. Click on “Donate to the Historical Commission,” then fill out the form, select “MS Baptist Historical Commission” and how much you will donate (I suggest at least $15 to cover their costs), and how many copies of the book you want.

Here is the link: https://mbcb.org/historicalcommission/

Mississippi Baptists and the civil rights struggle in the 1950s and 1960s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court struck down public school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, saying, “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Southern Baptist Convention, meeting only weeks later, became the first major religious denomination to endorse the decision, saying, “This Supreme Court decision is in harmony with the constitutional guarantee of equal freedom to all citizens, and with the Christian principles of equal justice and love for all men.” Mississippi Baptists, however, would have none of it. A.L. Goodrich, editor of The Baptist Record, accused the Southern Baptist Convention of inconsistency on the issue for not endorsing other types of integration as well. Goodrich was “indignant” at this example of “the church putting its finger in state matters,” but he told Mississippi Baptist readers that they “need not fear any results from this action.” First Baptist Church, Grenada (Grenada) made a statement condemning the Supreme Court decision. The Mississippi Baptist Convention, meeting November 16-18, 1954, passed several resolutions, but it made no mention of the Supreme Court decision.1

The Supreme Court deferred application of integration, and Mississippi’s governor, Hugh White, met with Black leaders, expecting that they would agree to maintain segregated schools if the state improved funding for Black schools. H.H. Humes represented the largest Black denomination in the state, as president of the 400,000-member General Missionary Baptist Convention. He responded to the governor, “the real trouble is that for too long you have given us schools in which we could study the earth through the floor and the stars through the roof.”2

In the 1950s, most White Baptists were content with a paternalistic approach of sponsoring ministry to Black Baptists, while keeping their schools, churches and social interaction segregated. There were some rare exceptions. Ken West recalls attending Gunnison Baptist Church, (Bolivar) in the 1950s, when the congregation had several Black members of the church, mostly women, who actively participated in WMU. However, most White Baptists agreed with W. Douglas Hudgins, pastor of First Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds), who told reporters that he did not expect “Negroes” to try to join his church. When pressed specifically about the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court, Douglas evasively called it “a political question and not a religious question.” Alex McKeigney, a deacon from First Baptist Church, Jackson, was more direct, saying that “the facts of history make it plain that the development of civilization and of Christianity itself has rested in the hands of the white race” and that support of school desegregation “is a direct contribution to the efforts of those groups advocating intermarriage between the races.” Dr. D.M. Nelson, president of Mississippi College, wrote a tract in support of segregation that was published by the White Citizens’ Council in 1954. In the tract, Nelson said that in part, the purpose of integration was “to mongrelize the two dominant races of the South.” Baptist lay leader Owen Cooper recalled that during the 1950s, he avoided the moral issue that troubled him later: “To be quite honest I did not ask myself what Jesus Christ would have done had He been on earth at the time. I didn’t ask because I already knew the answer.”3

In 1960, Baptist home missionary Victor M. Kaneubbe sparked controversy over segregated schools for another racial group in Mississippi, the American Indians. Kaneubbe was a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, who came to Mississippi to do mission work with the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. However, since his wife was White, no public schools would admit their daughter, Vicki. The White schools denied Vicki because she was Choctaw, and the Choctaw schools denied her because she was White. Kaneubbe enlisted the support of many White Baptists who campaigned for Vicki. This eventually led to the establishment Choctaw Central High School on the Pearl River Reservation in Neshoba County, an integrated school that admitted students with partial Choctaw blood.4

The minutes of Woodville Heights Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds) illustrate how local churches began to struggle with the issue of integration in the 1960s. At the monthly business meeting of Woodville Heights in August 1961, the issue of racial integration came up. The minutes read, “Bro. Magee gave a short talk on integration attempts. Bro. Sullivan gave his opinion on this subject. Bro. Sullivan said he would contact Sheriff Gilfoy concerning the furnishing of a Deputy during our services.” Interestingly, the very next month, the pastor, Dr. Percy F. Herring, resigned, and so did one of the trustees, Samuel Norris. In his resignation letter, Herring did not make a direct reference to the integration issue, only saying, “My personal circumstances and the situation here in the community have combined to bring me to the conclusion that I should submit my resignation as Pastor of this church.”5

Woodville Heights was not alone in the struggle. Throughout the 1960s, many Mississippi Baptists wrestled with racism in their local churches, associations, and the state convention. In the early part of the decade, it was common for Southern Baptist churches in Mississippi to have what was called a “closed door policy” against attendance by Black people. White Baptists were known to be active in the Ku Klux Klan, such as Sam Bowers, leader of the White Knights of the KKK, who taught a men’s Sunday school class at a Baptist church in Jones County. Some Baptist leaders were disturbed by the violence of the KKK. In November 1964, a few months after the murders of civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Owen Cooper presented a resolution on racism at the state convention. Cooper’s resolution, which was adopted, recognized that “serious racial problems now beset our state,” and said, “we deplore every action of violence… We would urge all Baptists in the state to refrain from participating in or approval of any such acts of lawlessness.” In 1965, it was front-page news in The Baptist Record when First Baptist Church, Richmond, Virginia admitted two Nigerian college students as members. When First Baptist Church, Montgomery, Alabama adopted an “open door policy” toward all races the same year, it was again news in The Baptist Record. Clearly, it was not yet the norm in White Mississippi Baptist churches.6

As the decade progressed, some Mississippi Baptists began to accept integration and work toward racial justice and reconciliation. Tom Landrum, a Baptist layman in Jones County, secretly spied on the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Landrum’s reports to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) were instrumental in the arrest of the Klansmen who killed civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer in 1965. Earl Kelly, in his presidential address in 1966, told the Mississippi Baptist Convention that “the race question” had to be faced. Baptist deacon Owen Cooper took this challenge seriously, helping to charter and becoming chairman of Mississippi Action for Progress (MAP) on September 13, 1966; MAP was able to secure millions of dollars to keep alive Head Start programs, which primarily benefitted impoverished Black children, that were in danger of losing their funds. When civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, The Baptist Record quoted Baptist leaders who expressed “shock, grief and dismay at the murder” of King. In 1969, Jerry Clower, the popular Mississippi entertainer and member of First Baptist Church, Yazoo City (Yazoo), was speaking out against racism at Baptist events. Clower confessed that as a child, he was taught that “a Negro did not have a soul, but he found out he was wrong when he became a Christian.” By that year, 1969, all the state colleges and hospitals had agreed to sign an assurance of compliance with racial integration.7

(Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.)

SOURCES:

1 Jesse C. Fletcher, The Southern Baptist Convention: A Sesquicentennial History (Nashville: Broadman and Holman Publishers, 1994), 200; Annual, Southern Baptist Convention, 1954, 36; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1954, 45-49; The Baptist Record, June 10, 1954, 1, 3; July 8, 1954, 4.

3 Ibid, 62-63; Letter from Ken West, Leland, Mississippi, to Bob Rogers, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 28 January 2022, Original in the hand of Robert C. Rogers; D. M. Nelson, Conflicting Views on Segregation (Greenwood, MS: Educational Fund of the Citizens’ Council, 1954), 5, 10; The Clarion-Ledger, April 4, 1982, cited in Dittmer, 63.

4 Jamie Henton, “Their Culture Against Them: The Assimilation of Native American Children Through Progressive Education, 1930-1960s,” Master’s Theses, University of Southern Mississippi, 2019, 85-92.

5 Minutes, Woodville Heights Baptist Church, Jackson, Mississippi, August 9, 1961; September 6, 1961.

6 Curtis Wilkie, When Evil Lived in Laurel: The ‘White Knights’ and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer (New York: W.W. North & Company, 2021), 26, 43-51; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1964, 43-44; The Baptist Record, January 28, 1965, 1; April 29, 1965, 2.

7 Wilkie, 20, 138; Dittmer, 377-378; The Baptist Record, November 17, 1966, 1, 3; December 21, 1967; April 11, 1968, 1; July 17, 1969, 1, 2; November 29, 1969, 1.

A challenge to Calvinism: M.T. Martin and the controversy that rocked Mississippi Baptists in the 1890s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

In 1893, a controversy began in the Mississippi Baptist Association and eventually spread across the state. Jesse Boyd wrote, “Its rise was gradual, its force cumulative, its aftermath bitter, and its resultant breach slow in healing.”1 While it may have been a quibble over words rather than a serious breach of Baptist doctrine, it illustrates how Mississippi Baptists clashed over Calvinist doctrine by the end of the 19th century.

M. Thomas Martin was professor of mathematics at Mississippi College from 1871-80, and he also served as the business manager of The Baptist Record from 1877-81. He moved to Texas in 1883, where he had great success as an evangelist for nearly a decade, reporting some 4,000 professions of faith. However, his methods of evangelism drew critics in Texas. According to J.H. Lane, while Martin was still in Texas, “the church in Waco, Texas, of which Dr. B. H. Carroll is pastor, tried Bro. Martin some years ago, and found him way out of line, for which he was deposed from the ministry.” In 1892 Martin returned to Mississippi and became pastor of Galilee Baptist Church, Gloster (Amite). Martin preached the annual sermon at the Mississippi association in 1893. His sermon had such an effect on those present, that the clerk entered in the minutes, “Immediately after the sermon, forty persons came forward and said that they had peace with God, and full assurance for the first time.” The following year, Mississippi association reported on Martin’s mission work in reviving four churches, during which he baptized 19 people, and another 60 in his own pastorate. Soon Mississippi Baptists echoed the Texas critics that he was “way out of line,” not because he baptized so many, but because so many were “rebaptisms.”2

The crux of the controversy was Martin’s emphasis on “full assurance,” which often led people who had previously professed faith and been baptized, to question their salvation and seek baptism again. In 1895, the Mississippi association called Martin’s teachings “heresy” and censured Martin and Galilee for practicing rebaptism “to an unlimited extent, unwarranted by Scriptures.” When the association met again in 1896, resolutions were presented against Galilee for not taking action against their pastor, but other representatives said they had no authority to meddle in matters of local church autonomy. As a compromise, the association passed a resolution requesting that The Baptist Record publish articles by Martin explaining his views, alongside articles by the association opposing those views, “that our denomination may be… enabled to judge whether his teachings be orthodox or not.” The editor of The Baptist Record honored the request, and Martin’s views appeared in the paper the following year. The association enlisted R.A. Venable to write against him, but Venable declined to do so. Martin also published a pamphlet entitled The Doctrinal Views of M.T. Martin. When these two publications appeared, what had been little more than a dust devil of controversy in one association, developed into a hurricane encompassing the entire state.3

Most of Martin’s teachings on salvation were common among Baptists. Even his opponent, J.H. Lane, admitted, “Some of Bro. Martin’s doctrine is sound.” Martin taught that the Holy Spirit causes people to be aware that they are lost, and the Spirit enables people to repent and believe in Christ. He taught that people are saved by grace alone, through faith, rather than works, and when people are saved, they should be baptized as an act of Christian obedience. Martin said that salvation does not depend on one’s feelings, and that children of God have no reason to question their assurance of salvation.

These teachings were not controversial. What was controversial, however, was what Lane called “doctrine that is not Baptist,” and what T.C. Schilling said “is not in accord with Baptists.” Martin said if a man doubted his Christian experience, then he was never true a believer.

He considered such doubt to be evidence that one’s spiritual experience was not genuine, and the person needed to be baptized again. “If you have trusted the Lord Jesus Christ,” Martin would say, “you will be the first one to know it, and the last one to give it up.” He frequently said, “We do wrong to comfort those who doubt their salvation, because we seek to comfort those whom the Lord has not comforted.” Therefore, Martin called for people who questioned their salvation to receive baptism regardless of whether they had been baptized before. “I believe in real believer’s baptism, and I do not believe that one is a believer until he has discarded all self-righteousness, and has looked to Christ as his only hope forever… I believe that every case of re-baptism should stand on its own merits, and be left with the pastor and the church.”4

The 1897 session of the Mississippi association took further action against Martinism. They withdrew fellowship from Zion Hill Baptist Church (Amite) for endorsing Martin and urged Baptists not “to recognize him as a Baptist minister.” The association urged churches under the influence of Martinism to return to the “old faith of Baptists,” and if not, they would forfeit membership. When the state convention met in 1897, some wanted to leave the issue alone, but others forced it. The convention voted to appoint a committee to report “upon the subject of ‘Martinism.’” Following their report, the convention adopted a resolution of censure by a vote of 101-16, saying, “Resolved, That this Convention does not endorse, but condemns, the doctrinal views of Prof. M. T. Martin.” While a strong majority condemned Martinism, a significant minority of Baptists in the state disagreed. From 1895 to 1900, the Mississippi association declined from 31 to 22 churches, and from 3,042 to 2,208 members. In 1905, the state convention adopted a resolution expressing regret for the censure of Martin in 1897.5

Earl Kelly observed two interesting doctrinal facts that the controversy over Martinism revealed about Mississippi Baptists during this period: “First, the Augustinian conception of grace was held by the majority of Mississippi Baptists; and second, Arminianism was beginning to make serious inroads into the previously Calvinistic theology of these Baptists.” It is significant that Mississippi association referred to Martinism as a rejection of “the old faith of Baptists,” and that when J.R. Sample defended Martin, Lane pointed out that Sample was formerly a Methodist.6

(Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.)

SOURCES:

1 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists of Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 178-179.

2 Boyd, 196-197; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1893; 7; Z. T Leavell and T. J. Bailey, A Complete History of Mississippi Baptists from the Earliest Times, vol. 1 (Jackson: Mississippi Baptist Publishing Company, 1904), 68-69; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

3 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1895; 1896, 9.

4 Boyd, 179-180; The Baptist Record, March 18, 1897, May 6, 1897, June 24, 1897, 2.

5 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1897, 6, 14; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1897, 13, 17, 18, 22, 31; 1905, 47-48; Leavell and Bailey, vol. 1, 70; Boyd, 198. Martin died of a heart attack while riding a train in Louisiana in 1898, and he was buried in Gloster.

6 Earnest Earl Kelly, “A History of the Mississippi Baptist Convention from Its Conception to 1900.” (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Lousville, Kentucky, 1953), 114; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

Preaching to the spirits in prison. An interpretation of 1 Peter 3:18-20

Copyright by Bob Rogers, Th.D.

For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that He might bring you to God, after being put to death in the fleshly realm but made alive in the spiritual realm. In that state He also went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison who in the past were disobedient, when God patiently waited in the days of Noah while an ark was being prepared. – 1 Peter 3:18-20, HCSB

There are three facts about 1 Peter 3:18-20 which cannot be ignored:

- There was a story in a Jewish book called First Enoch about Enoch (Genesis 5:21-24) who made a journey to the supernatural beings who seduced human women (Genesis 6:1-4). This was at the time of Noah (Genesis 6:5-8). In First Enoch, Enoch is said to preach condemnation on these beings.

- First Enoch was well known in the first century, for Jude 9-10 and Jude 14 and 2 Peter 2:4-5 refer to stories which are in the older book of First Enoch, as does this passage.

- In Greek, verse 19 begins with three words which are transliterated in English letters: en o kai, which in Greek manuscripts would be run together: enokai. Compare that to the name Enoch.

What does all this mean? 1 Peter is well-known for clever arrangements of words. It seems that he is making a pun on the name Enoch in verse 19 because he is referring to a story about Enoch known to his readers.

First Peter 3:18 says that after Jesus died and was buried, he was “made alive in the spiritual realm.” Yet before His resurrection was physically displayed on Easter, He took care of some other-worldly business. He made a journey to the lower world of the dead (see Romans 10:7, Ephesians 4:9), where He “made a proclamation to the spirits in prison” (verse 19). The term “spirits” is never used to mean dead men, so it must refer to the fallen angels of Noah’s day, whom God had bound in prison (Jude 6, 1 Peter 2:4, Revelation 20:1-2, First Enoch 10).

Nowhere does Peter say that Jesus went to hell as punishment for our sins. The journey was to “Tartarus” (2 Peter 2:4, incorrectly translated “hell” in some translations). Tartarus was a Greek name for a place they believed all dead went, good and bad, like Hebrew word Sheol in the Old Testament. This journey was not forced upon Jesus; He went rather than suffer agony while in the grave.

Peter’s readers lived in a world where belief in evil spirits was universal. Some saw the Roman persecution coming, and they longed for protection from the evil spirits of the Romans which they feared might overcome the power of Christ. Peter comforted them with the news that Christ had defeated the most horrible of all spirits, the greatly feared fallen spirits of Noah’s day. In folklore, these spirits were considered to be the most wicked of all spirits.

First Peter 3:19 says Christ made proclamation to these spirits. This does not mean He was giving those who died before the time of His crucifixion a chance to believe the gospel, for he was speaking to spirits, not men. It does not even mean he was presenting the gospel to the spirits, for this Greek word can be used simply to “declare” or “proclaim” (the translation used in many versions, see also Revelation 5:2) with no implication of the gospel being presented. No, Jesus was announcing that He had defeated them! Thus, in verse 22, Peter says He ascended to heaven “with angels, authorities, and powers subject to Him.”

This proclamation of victory over the fallen angels was reassurance to Peter’s readers that they shouldn’t fear evil powers around them, for Christ is more powerful.

A second interpretation of 1 Peter 3:18-20 is worth considering. This view says that Jesus did not descend at all, but that in the same spirit of Jesus which has always existed, He had preached to the evil men of Noah’s day and given them a chance to repent. This takes verse 19 to refer to “in the spiritual realm” in verse 18.

This view appears to answer some questions people have, because it claims that the people living before the time of Jesus’ crucifixion had the same opportunity to repent as we do, for the spirit of Christ has always been around to give them the message, whether it be seen in Noah or Moses or a prophet.

This view is correct in noting that verse 19 simply says, “He went,” not “He descended.” It is also less complicated than the other view.

However, this second explanation seems to take things out of order. In verse 18, Peter refers to the cross, and in verse 22, he refers to the ascension. Verses 19-20 should refer to something in between, not to Jesus’ spirit back in the days of Noah.

Whatever interpretation we+9 follow, we would do well to remember to present it in “gentleness and respect” (1 Peter 3:15).

Further reading: Ernest Best, 1 Peter in the New Century Bible Commentary Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1971), 135-146.

E.G. Selwyn, The First Epistle of St. Peter, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1946), 197-202.

Ray Summers, “1 Peter” in volume 12 of The Broadman Bible Commentary (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1972), 163-164.

How Mississippi Baptist views on alcohol evolved in the 19th century

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

During the 1820s and 1830s, Baptists gradually took a stronger stand against liquor. In 1820, Providence Baptist Church (Forrest County) discussed the question, “Is it lawful, according to scripture, for a member of a church to retail spiritous liquors?” The church could not agree on a position. However, in 1826, the influential Congregationalist pastor Lyman Beecher began a series of sermons against the dangers of drunkenness. He called on Christians to sign pledges to abstain from alcohol, igniting the temperance movement in America. The question came before the Mississippi association in 1827, and the association stated that it “considers drunkenness one of the most injurious and worst vices in the community.” In 1830, the Pearl River association admonished any churches hosting their meetings, “Provide no ardent spirits for the association when she may hereafter meet, as we do not want it.” In 1831, Pearl River association thanked the host church for obeying their request, and in 1832, the association humbly prayed for “the public, that they will not come up to our Association with their beer, Cider, Cakes, and Mellons, as they greatly disturb the congregation.” Likewise in 1832, the Mississippi association resolved, “that this Association do discountenance all traffic in spirituous liquors, beer, cider, or bread, within such a distance of our meetings as in any wise disturb our peace and worship; and we do, therefore, earnestly request all persons to refrain from the same.”

It had always been common to discipline members for drunkenness, but as the temperance movement grew in America, Mississippi Baptists moved gradually from a policy of tolerating mild use of alcohol, toward a policy of complete abstinence. A Committee on Temperance made an enthusiastic report in 1838 of “the steady progress of the Temperance Reformation in different parts of Mississippi and Louisiana; prejudices and opposition are fast melting away.” In 1839, D. B. Crawford gave a report to the convention on temperance which stated, “That notwithstanding, a few years since, the greater portion of our beloved and fast growing state, was under the influence of the habitual use of that liquid fire, which in its nature is so well calculated to ruin the fortunes, the lives and the souls of men, and spread devastation and ruin over the whole of our land; yet we rejoice to learn, that the cause of temperance is steadily advancing in the different parts of our State… We do therefore most earnestly and affectionately recommend to the members of our churches… to carry on and advance the great cause of temperance: 1. By abstaining entirely from the habitual use of all intoxicating liquors. 2. By using all the influence they may have, to unite others in this good work of advancing the noble enterprise contemplated by the friends of temperance.” Local churches consistently disciplined members for drunkenness, but they were slower to oppose the sale or use of alcohol. For example, in May 1844, “a query was proposed” at Providence Baptist Church (Forrest) on the issue of distributing alcohol. After discussion, the church took a vote on its opposition to “members of this church retailing or trafficking in Spirituous Liquors.” In the church minutes, the clerk wrote that the motion “unanimously carried in opposition” but then crossed out the word “unanimously.” In January 1845, Providence voted that “the voice of the church be taken to reconsider” the matter of liquor. The motion passed, but then they tabled the issue, and it did not come back up. In March of that year, a member acknowledged his “excessive use of arden[t] spirits” and his acknowledgement was accepted; he was “exonerated.”

By the 1850s, the state convention was calling not only for abstinence, but for legal action as well. In 1853, the convention adopted the report of the Temperance Committee that said, “The time has arrived when the only true policy for the advocates of Temperance to pursue, is… to secure the enactment by the Legislature of a law, utterly prohibiting the sale of ardent spirits in any quantities whatsoever.” They endorsed the enactment of the Maine Liquor Law in Mississippi. In 1851, Maine had become the first state to pass a prohibition of alcohol “except for mechanical, medicinal and manufacturing purposes,” and this law was hotly debated all over the nation, as other states considered adopting similar laws. In 1854, the Mississippi legislature banned the sale of liquors “in any quantity whatever, within five miles of said college,” referring to Mississippi College. In 1855, Ebenezer Baptist Church (Amite) granted permission to the ”sons of temperance” to build a “temperance hall” on land belonging to the church. In 1860, a member of Bethesda Baptist Church (Hinds) confessed he “had been selling ardent spirits by the gallon” and “acknowledged he had done wrong and would do so no more.” He was “requested by the church not to treat his friends with spiritous [sic] liquors when visiting his house.”

Frances E. Willard, one of the most famous temperance activists in the nation, spent a month in Mississippi in 1882 and announced, “Mississippi is the strongest of the Southern State W.C.T.U. organizations.” Every Baptist association had a temperance committee. T.J. Bailey, a Baptist minister, was the superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League. Prohibition of alcohol was such an emotionally charged issue that a liquor supporter assassinated Roderic D. Gambrell, son of Mississippi Baptist leader J.B. Gambrell and the editor of a temperance newspaper, The Sword and Shield. Nevertheless, the temperance movement was so successful that by 1897, all but five counties in Mississippi had outlawed the sale of liquor.

Book review: “Baptist Successionism: A Critical Review”

W. Morgan Patterson is a Southern Baptist historian, educated at Stetson University, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and Oxford University. This book was published in 1979, but I recently picked it up and read it in one day.

This is a concise book (four chapters, 75 pages) that analyzes the failures of the sloppy historical research of Baptists, such as Landmarkists, who believe Baptist churches are in a direct line of succession from New Testament times. The introduction explains there are four different variations of successionist writers, from those who believe they can demonstrate it and that is necessary, to those who believe neither. Chapter one explains how the successionist view was not that of the earliest Baptists, but in the 19th century it was formulated by G.H. Orchard and popularized by J.R. Graves. Chapter two shows how the successionist writers misused their sources. Chapter three shows their poor logic. Chapter four exams some of the motivations behind this erroneous view. The conclusion sums up the book, noting that the successionist view was predominant in the 19th century, but thanks to bold historians like William Whitsitt, whose research debunked the theory in the 1890s, the successionist view became a minority position among Baptist historians in the 20th century.

Patterson is scholarly historian, and he may assume a little too much about the historical knowledge of the reader when he refers to the Münster incident on page 22 without explaining that this was a violent takeover of the city of Münster, Germany in 1534 by an Anabaptist fringe group that came to be associated with Anabaptists and Baptists in the minds of their opponents, and he refers to the Whitsitt controversy on page 24 without explaining the controversy until later.

Patterson could have made his argument stronger by giving more specific details about the heretical beliefs of groups claimed by successionist writers to be Baptists, such as the Donatists, Paulicians, Cathari, etc.

While Patterson’s book is concise, it is substantive, and his reasons are sound. This is an effective critique.

The Presbyterian spy in the Baptist Church

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

The first Baptist church in Mississippi not only faced persecution from the Catholic church but was infiltrated by a Presbyterian spy.

In the 1790s the Spanish controlled the Natchez District, outlawing all public worship that was not Roman Catholic. However, in 1791, Baptist preacher Richard Curtis, Jr. organized a church on Coles Creek, 20 miles north of Natchez, later known as Salem Baptist Church. The Spanish governor, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, allowed private Protestant worship, hoping to win them over to Catholicism. However, when the priests in Natchez complained of the public worship of the Baptist congregation, Gayoso arrested Curtis in April 1795, and threatened to confiscate his property and expel him from the district if he didn’t stop. Curtis agreed, but he and his congregation decided that didn’t prohibit them from having prayer meetings and “exhortation.” Curtis even performed a wedding in May for his niece but did so secretly.

Sometime in 1795, Ebenezer Drayton was sent by Governor Gayoso to infiltrate the Baptist meetings and send back reports. He reported that at first the Baptists were “afraid of me, and they immediately guessed that I was employed by Government, which I denied.” However, he convinced them that his “feelings were much like theirs… my being of the Protestant Sect called Presbyterians and they of the Baptist.” Thus reassured, they allowed Drayton to attend their meetings, but Drayton wrote letters informing the Spanish “Catholic Majesty,” as he called him, of their activities.

Thanks to Drayton, the Spanish learned that Curtis started to go back to South Carolina, but the congregation sent four men to chase him down and insist he stay and preach to them. Considering this God’s will, Curtis returned and continued to preach. Drayton reported that Curtis agonized over his decision to stay, but told his congregation, “God says, fear not him that can kill the body only, but fear him that can cast the soul into everlasting fire… I am not ashamed not afraid to serve Jesus Christ… and if I suffer for serving him, I am willing to suffer… I would not have signed that paper if I had then known that it is the will of God that I should stay here.”

Drayton had a low opinion of Curtis and the Baptists. He wrote that the Baptists “are weak men of weak minds, and illiterate, and too ignorant to know how inconsistent they act and talk, and that they are only carried away with a frenzy or blind zeal about what they know not what…” However, Curtis seemed sharp enough to realize there was spy among them, because in July 1795, he published a letter in Natchez, explaining why he stayed, defending his religious freedom, and saying he was deeply hurt by “the malignant information against us, laid in before the authority by some who call themselves Christians.”

Thanks to their spy, the Spanish knew exactly when and where the congregation met. In August 1795, they sent a posse to arrest Curtis and two of his converts, but they fled to South Carolina, where they remained until the Spanish were forced by American authorities to leave the Natchez District.

Dr. Rogers is the author of a new history of Mississippi Baptists, to be published in 2025.

Guest post: What happens to people who die having never heard about Jesus?

Copyright by Wayne VanHorn.

Dr. Wayne VanHorn is Dean at the School of Christian Studies and Arts at Mississippi College. This post was first shared on his Facebook page and is shared here with his permission.

I remember the first time someone asked me, “What happens to all those people who die having never heard about Jesus?” They did not think it was fair for them to go to hell because they happened to be born at the wrong time and place to be in the path of Christian witnesses. Admittedly, I was stumped. I had to do some Bible study and some serious thinking before I could let this question go. Over the years, a few things have happened or come to mind that help me answer the question more substantively.

1. I met a man from in-land China. He grew up in Communism whereas I grew up in Church. He was fed a steady diet of atheistic propaganda: no God, no Jesus, etc. while I was taken to church every time the door was open. One day my Chinese friend was listening to the radio. Poor atmospheric conditions in one part of the world some how enabled an evangelistic radio message to skip across the atmosphere; my Chinese friend heard about Jesus “accidentally.” With no Bible, no Church, no preacher, no missionary, or any other evangelic witness, my Chinese friend heard the Gospel, accepted Jesus, and devoted his life to telling his countrymen about the same Lord who is my Savior. I met “Peter” (we could not pronounce his Chinese name) at New Orleans Seminary. This encounter reminded me that just because I do not know how people in remote areas can hear the Gospel does not mean that they do not hear the Gospel.

2. I came across Titus 2:11, “For the grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation to all men” (NASB) or as the KJV reads, “For the grace of God that bringeth salvation hath appeared to all men.” Once again I realized God is at work in ways I might not know about, might not understand, might be oblivious to, etc.

3. As I studied the Bible, I learned more and more of a loving God, who has gone out of His way to make it possible for sinners to repent and to return to Him.

4. In his book, True for You But Not for Me, Paul Copan wrote, “Third, God’s loving and just character assures us that he won’t condemn anyone for being born at the wrong place and time.” (Copan, p. 189)

5. The Greek text of Titus 2:11, “Ἐπεφάνη γὰρ ἡ χάρις τοῦ θεοῦ σωτήριος πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις” (Tit 2:11 NA27) utilizes the dative- locative-instrumental form of the adjective “all” and of the noun “men” or “people.” This means God’s salvation-bringing grace has appeared: a. to all people b. for all people. While I cannot fully understand just how God does that, it is not beyond HIS ability to do it.

6. Any impulse or concern I have regarding the un-evangelized is probably God prompting me to share His Gospel with others.

7. Jesus is the only way to salvation, to God, and to heaven, if not, Jesus died in vain. If any religion or any devotion or any sincerely held religious view will save people, Jesus’ did not need to endure the cross and despise the shame. BUT He did endure the cross and He did despise the shame for the joy set before Him (Heb. 12:2). So don’t worry about the un-evangelized, pray for them and witness to them whenever you get a chance. But whatever else you do, don’t let an atheist talk you out of your faith because he/she says it’s unfair that some people will go to hell because they did not get to hear about Jesus. Let me know what you think.

Rev. T. C. Teasdale’s daring adventure with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most amazing but lesser-known stories of the Civil War is how a Mississippi Baptist preacher got both Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln to agree to help him sell cotton across enemy lines in order to fund an orphanage. Although the plan collapsed in the end, the story is still fascinating.

Since over 5,000 children of Mississippi Confederate soldiers were left fatherless, an interdenominational movement started in 1864 to establish a home for them. On October 26, 1864, the Mississippi Baptist Convention accepted responsibility for the project. The Orphans’ Home of Mississippi opened in October 1866 at Lauderdale, after considerable effort, especially by one prominent pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale.1

Rev. Teasdale was in a unique position to aid the Orphans’ Home, because of his influential contacts in both the North and South. A New Jersey native, he came to First Baptist Church, Columbus, Mississippi in the 1850s from a church in Washington, D.C. When the Civil War erupted, he left his church to preach to Confederate troops in the field. In early 1865, he returned from preaching among Confederate soldiers to assist with the establishment of the Orphans’ Home of Mississippi. He launched a creative and bold plan to raise money and solve a problem of donations. A large donation of cotton was offered to the orphanage, and the cotton could bring 16 times more money in New York than in Mississippi, but how could they sell it in New York with the war still raging? Since Teasdale had been a pastor in Springfield, Illinois and Washington, D.C. and had preached to the Confederate armies, he was personally acquainted with both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln (from Illinois) and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and many of their advisers. In February and March 1865, he set out on a dangerous journey by horseback, boat, railroads, stagecoach and foot, dodging Sherman’s march through Georgia, crossing through the lines of the armies of both sides, and conferred in Richmond and Washington, seeking permission from both sides to sell the cotton in New York for the benefit of the orphanage.2

Confederate President Davis readily agreed, and on March 3, 1865, Davis signed the paper granting permission for the sale. Next, Dr. Teasdale slipped across enemy lines and entered Washington, a city he knew well, since he was a former pastor in the city. He waited in line for several days for an audience with President Lincoln, but he could not get in, since government officials in line were always a higher priority than a private citizen. Finally, he sent a note to Mr. Lincoln, whom he knew when they both lived in Springfield, Illinois, saying that he was now a resident of Mississippi and that he was there on a mission of mercy. Lincoln received him, and he listened to the plea for cotton sales to support the orphanage, but the president was skeptical. Why should he help Mississippi, a State in rebellion against the United States? In his autobiography, Teasdale records Lincoln’s words: “We want to bring you rebels into such straits, that you will be willing to give up this wicked rebellion.” Dr. Teasdale replied, “Mr. President, if it were the big people alone that were concerned in this matter, I should not be here, sir. They might fight it out to the bitter end, without my pleading for their relief. But sir, when it is the hapless little ones that are involved in this suffering, who, of course, who had nothing to do with bringing about the present unhappy conflict between the sections, I think it is a very different case, and one deserving of sympathy and commiseration.” Lincoln instantly said, “That is true; and I must do something for you.” With that, Lincoln signed the paper, granting permission for the sale. It was March 18, 1865. However, a few weeks later, on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army to Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant. By the time Teasdale returned home, the war was over, the permission granted by Jefferson Davis no longer had authority, Lincoln was assassinated, and Teasdale abandoned his plans. Teasdale said, “This splendid arrangement failed, only because it was undertaken a little too late.” Undaunted, Dr. Teasdale volunteered as a fundraising agent for the orphanage and staked his large private fortune on its success. Rarely has there been a more daring donor to a Christian cause!3

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 12-17; 1867, 29-31.

2 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists in Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 131.

3 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 173-174, 187-203; Boyd, 130-132; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 14-16.

How to get ready for Easter

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

When I served as a Baptist pastor in Rincon, Georgia, I had the unique experience of putting on a white wig and an old robe borrowed from a Methodist, to give a dramatic presentation of the founding pastor of the oldest Lutheran Church in North America. The historic pastor’s name was Johann Boltzius, and his church was Jerusalem Lutheran Church, founded in 1734 in the Ebenezer Community in Effingham County, Georgia, some 30 miles north of Savannah.

School children came from all over Georgia to the retreat center at Ebenezer to learn Georgia history. They visited Savannah, and they also came to the old Jerusalem Lutheran Church, whose sanctuary was built in 1769, to hear me tell the story, in costume, of Boltzius who served a congregation that fled to the New World from Salzburg, Austria, in search of religious freedom.

After the presentation, students were given an opportunity to ask “Pastor Boltzius” questions. One day in March, a student asked me why it was so dark in the church. With a gleam in my eye, I explained that it was Lent, a season in which members of that church remembered Jesus’ death on the cross for our sins. Members of the church fasted, prayed, and thought of other ways to make sacrifices in memory of Jesus, and during this time, they kept the window shutters closed. In fact, on Good Friday, they came into the church and sang songs about Jesus’ death, and then blew out all of the candles and went home in total darkness. The students reflected on that quietly, and I paused. Then I waved my hand at the shutters and shouted, “But on Easter Sunday morning, they threw open the shutters, let the light in, and celebrated, because Jesus is alive!”

Whether or not your church observes the tradition of Lent, it is an important reminder of how any Christian can get ready for Easter, by first reflecting on the suffering of Christ. I encourage you to read the story of the crucifixion from the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Spend time alone, silent, reflecting on it. Fast and pray. Think about your own sin, your own struggles, your own sorrows, and how the suffering of Christ forgives, redeems and renews you. Meditate on the dark, and the light will brighten you more when it comes. Like that church in Georgia that threw open their shutters, if we will remember how dark it was when Christ died, we will appreciate all the more how glorious it was that He arose!

How Christians can respond to rejection

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

Everybody has to deal with rejection. Even Jesus Christ was rejected by his hometown of Nazareth. They didn’t like it when He declared His Messianic mission would include Gentiles, so they tried to throw him off the local cliff (see Luke 4:23-29).

In one of the greatest face-to-face confrontations in history, Jesus faced their rejection and “passed right through the crowd and went on His way” (Luke 4:30). That’s how He handled it, how do we?

Let’s be clear about something. You and I are not Jesus, so we first need to examine our own actions and motives in the light of scripture, to make sure our rejection isn’t a deserved rebuke for ungodly behavior. Peter writes, that if we are ridiculed “for the name of Christ” we are blessed, yet cautions “let none of you sufer as a murderer, a thief, an evildoer, or a meddler” (1 Peter 4:15-16). Most of us would be okay if he hadn’t added “meddler.” So before anything else, let’s take an honest look at why we are rejected.

If, after taking an honest look at ourselves, we know that our rejection is because we have lived for Christ, and done so with integrity, then what? Scripture tells us three ways that Christians can face rejection: rejoice, remember and rely.

- Rejoice (Matthew 5:10-12). Jesus concluded the “Beatitudes” by telling His followers that when we are rejected, we should rejoice: “Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for the kingdom of heaven is theirs. You are blessed when they insult you and persecute you and falsely say every kind of evil against you becaue of me. Be glad and rejoice, because your reward is great in heaven. For that is how they persecuted the prophets who were before you.” We naturally want to get angry, defensive, or feel hurt, but Jesus tells us we should rejoice, because it shows we are on the right side! The early apostles did exactly that! When the Jewish Sanhedrin ordered them not to preach about Jesus, they left, “rejoicing that they were counted worthy to be treated shamefully on behalf of the Name” (Acts 5:41).

- Remember (John 15:19-21). Jesus reminded His disciples, “If the world hates you, understand that it hated me before it hated you. If you were of the world, the world would love you as its own. However, because you are not of the world, because I have chosen you out of it, the world hates you. Remember the word I spoke to you: ‘A servant is not greater than his master.’ If they persecuted me, they will also persecute you.” So whenever we are rejected, we don’t need to be surprised; we should remember that we were told to expect that it comes with the territory.

- Rely (2 Corinthians 1:8-11). The Apostle Paul is a great role model for handling persecution. He explained how it taught him to rely on God: “We don’t want you to be unaware, brothers and sisters, of our affliction that took place in Asia. We were completely overwhelmed– beyond our strength– so that we even despaired of life itself. Indeed, we felt that we had received the sentence of death, so that we would not trust in ourselves but in God who raises the dead. He has delivered us from such a terrible death, and he will deliver us. We have put our hope in him that he will deliver us again.”

Tony Evans says that whenever somebody rejects him because of the color of his skin, he remembers who he is in Christ. God says he is a child of the king. Thus, if they reject him, they are refusing royal blood in their presence. What a good example for us when people reject us because of our faith. Remembering that, we can rely on God, and rejoice!

Lost in New York without knowing it

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

When I was in the seventh grade, Dad was stationed at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York, in order to attend a nine-month Army Chaplain’s School. Almost every family on the post was there because of a chaplain attending the school. That meant all of the kids were “preacher’s kids,” and all of the families were new, because we would be transferred after a year and a whole new group would come the following school year. The school year was 1970-71. We could see the twin towers of the original World Trade Center under construction across the Hudson River. I went to Public School 104, which was in an Irish-Catholic neighborhood. It was a good school, with strict discipline and excellent academics.

Soon after school started that fall, we learned that on Wednesday afternoons they had “release time.” This was when students got out of school early and could go to their house of worship for religious education, if they wished. On that first Wednesday, all of us Protestant chaplains’ kids, being brand new, simply followed our Catholic friends down the street to their church and went to catechism. Then we returned to school in time to catch the Army bus back to Fort Hamilton.

Needless to say, the phones were ringing off the hook that night when we started telling our parents what kind of notebooks the nuns wanted us to buy for catechism. It only took one week for those chaplains and spouses to organize a Protestant religious education class for us to attend.

But what really got some parents rattled was what happened to my little sister Nancy and some of her friends during their first “release time.” Nancy, who was in second grade, and a few other Protestant chaplains’ daughters, went to the Catholic class but they missed the bus ride home. Their parents had the military police frantically searching the streets of New York for them. Imagine: little girls from places like Kansas, Texas and Mississippi, all lost on the streets of Brooklyn! When the girls were found, they didn’t know they had been lost.

Jesus said that he came to seek and save people who were lost (Luke 19:10). He told parables about a lost sheep, lost coin, and lost (prodigal) son, to illustrate how God goes to great lengths to find people (see Luke 15). Many don’t even know they are lost.

Ironically, my sister Nancy now lives in Brooklyn. She lives there with her husband Alex, and she rides the subway like a native. She doesn’t get lost there anymore; it’s her home. Likewise, when people turn to faith in Christ, they too are no longer lost. Like my sister, they have found their home at last.

(This story will be part of my upcoming book about taking a humorous yet serious look at the Christian life, called, Standing by the Wrong Graveside.)

Top 10 signs you’re in a bad church

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

I’ll admit it, some people have bad experiences with a church. Here are the top ten signs you’re in a bad church:

10. The church bus has gun racks.

9. Church staff: senior pastor, associate pator, socio-pastor.

8. The town gossip is the prayer coordinator.

7. Church sign says, “Do you know what Hell is? Come hear our preacher.”

6. Choir wears leather robes.

5. During greeting time, people take turns staring at you.

4. Karaoke worship time.

3. Ushers ask, “Smoking or non-smoking?”

2. Only song the organist knows: “We Shall Not Be Moved.”

- The pastor doesn’t want to come, but his wife makes him attend.

If your church is that bad, you might want to look for another church. But the fact is, that there is no perfect church, because the church is made up of imperfect people. The phrase the Bible uses to describe us is “sinners saved by grace.” So before you give up completely on the church, remember this: “Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25, ESV). If Jesus considered the church worth dying for, then we ought to consider the church worth living for.

An unknown poet put it well:

“If you should find the perfect church, without fault or smear

For goodness sake, don’t join that church, you’d spoil the atmosphere.

But since no perfect church exists, made of perfect men,

Let’s cease on looking for that church, and love the one we’re in.”

(This article will be part of my upcoming book about taking a humorous yet serious look at the Christian life, called, Standing by the Wrong Graveside.)