Category Archives: Christian Living

New devotional through Psalms & Proverbs in a year

Psalms & Proverbs Weekday Devotionals is my new e-Book with a daily reading plan to read through Psalms and Proverbs weekdays, Monday through Friday, in a year, accompanied by short devotional thoughts to edify your reading. Readings are arranged by weeks and days, not tied to months of the year, so you may begin at any time of the year.

Here is a sample, showing the first reading:

Week 1, Day 1

Read Psalm 1

Psalms 1:1 literally says the one who is blessed does not “walk,” or “stand,” or “sit” with the wicked. There is a progression here of lingering longer and longer with evil. That’s usually how we fall into sin– gradually. I know I have fallen into sin that way. The solution is in verse 2: Meditate on God’s Word both day and night! I pray these daily psalms and proverbs will protect you from sin and guide you with wisdom.

Read Proverbs 1:1-6

Proverbs 1:5 says a wise man will listen and increase his learning. James 1:19 says, “Everyone must be quick to hear, slow to speak…” An excellent resolution is to become a better listener in the New Year.

The e-Book is 164 pages. Buy it for just $2.99 on Amazon here.

As If Heaven Had Ordained It

“Not one word of all the good promises that the Lord had made to the house of Israel had failed; all came to pass.” – Joshua 21:45

When the Continental Congress gathered in Philadelphia in 1774 to unite against the British, they decided to open their proceedings in scripture and prayer. An Episcopalian minister named Jacob Duché was chosen. Before his prayer, rumors arrived that the British had attacked Boston. A frightened and receptive audience awaited as Duché read Psalms 35:1: “Contend, O LORD, with those who contend with me; fight against those who fight against me!” It was the assigned reading for the day in the Episcopal lectionary, but John Adams says members of the Continental Congress were stunned when they heard the words. Adams wrote, “It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that psalm to be read on that morning.” Have you had such an experience where the scripture seemed perfect for what you were going through at the time? I have several such scriptures marked in my Bible. Once when I was anxious about a situation at work, I read Psalm 34:4, “I sought the LORD, and he answered me and delivered me from all my fears.” That verse gave me sudden comfort. Eventually, everything worked out. Another verse that has helped me when facing a difficult decision is the promise of James 1:5, “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given him.” Praying over that promise, God has given me direction time after time. Once when I was a hospital chaplain, I visited a patient writhing in pain, asking me to pray. As I was about to pray, two nurses entered and gave her tablets to take for pain, then left the room. Immediately I began to pray, and I sensed God telling me to quote Psalm 23, so I did. Even before I finished the psalm, she grew peaceful and still. I finished quoting the psalm, added a few more words asking God for healing, and then I looked up. The patient was resting. Her sister-in-law looked at me, eyes wide in amazement. I said, “That pain medicine hasn’t had time to work, has it?” The sister-in-law said, “No, but Psalm 23 did!” What scripture has given you guidance, comfort, or strength “as if Heaven had ordained” it?

Prayer

Lord, my heart is full of anxieties and desires, but your word is full of good promises and timely guidance. As I read scripture, show me how it applies to my life as if Heaven had ordained it for this day.

How Mississippi Baptist views on alcohol evolved in the 19th century

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

During the 1820s and 1830s, Baptists gradually took a stronger stand against liquor. In 1820, Providence Baptist Church (Forrest County) discussed the question, “Is it lawful, according to scripture, for a member of a church to retail spiritous liquors?” The church could not agree on a position. However, in 1826, the influential Congregationalist pastor Lyman Beecher began a series of sermons against the dangers of drunkenness. He called on Christians to sign pledges to abstain from alcohol, igniting the temperance movement in America. The question came before the Mississippi association in 1827, and the association stated that it “considers drunkenness one of the most injurious and worst vices in the community.” In 1830, the Pearl River association admonished any churches hosting their meetings, “Provide no ardent spirits for the association when she may hereafter meet, as we do not want it.” In 1831, Pearl River association thanked the host church for obeying their request, and in 1832, the association humbly prayed for “the public, that they will not come up to our Association with their beer, Cider, Cakes, and Mellons, as they greatly disturb the congregation.” Likewise in 1832, the Mississippi association resolved, “that this Association do discountenance all traffic in spirituous liquors, beer, cider, or bread, within such a distance of our meetings as in any wise disturb our peace and worship; and we do, therefore, earnestly request all persons to refrain from the same.”

It had always been common to discipline members for drunkenness, but as the temperance movement grew in America, Mississippi Baptists moved gradually from a policy of tolerating mild use of alcohol, toward a policy of complete abstinence. A Committee on Temperance made an enthusiastic report in 1838 of “the steady progress of the Temperance Reformation in different parts of Mississippi and Louisiana; prejudices and opposition are fast melting away.” In 1839, D. B. Crawford gave a report to the convention on temperance which stated, “That notwithstanding, a few years since, the greater portion of our beloved and fast growing state, was under the influence of the habitual use of that liquid fire, which in its nature is so well calculated to ruin the fortunes, the lives and the souls of men, and spread devastation and ruin over the whole of our land; yet we rejoice to learn, that the cause of temperance is steadily advancing in the different parts of our State… We do therefore most earnestly and affectionately recommend to the members of our churches… to carry on and advance the great cause of temperance: 1. By abstaining entirely from the habitual use of all intoxicating liquors. 2. By using all the influence they may have, to unite others in this good work of advancing the noble enterprise contemplated by the friends of temperance.” Local churches consistently disciplined members for drunkenness, but they were slower to oppose the sale or use of alcohol. For example, in May 1844, “a query was proposed” at Providence Baptist Church (Forrest) on the issue of distributing alcohol. After discussion, the church took a vote on its opposition to “members of this church retailing or trafficking in Spirituous Liquors.” In the church minutes, the clerk wrote that the motion “unanimously carried in opposition” but then crossed out the word “unanimously.” In January 1845, Providence voted that “the voice of the church be taken to reconsider” the matter of liquor. The motion passed, but then they tabled the issue, and it did not come back up. In March of that year, a member acknowledged his “excessive use of arden[t] spirits” and his acknowledgement was accepted; he was “exonerated.”

By the 1850s, the state convention was calling not only for abstinence, but for legal action as well. In 1853, the convention adopted the report of the Temperance Committee that said, “The time has arrived when the only true policy for the advocates of Temperance to pursue, is… to secure the enactment by the Legislature of a law, utterly prohibiting the sale of ardent spirits in any quantities whatsoever.” They endorsed the enactment of the Maine Liquor Law in Mississippi. In 1851, Maine had become the first state to pass a prohibition of alcohol “except for mechanical, medicinal and manufacturing purposes,” and this law was hotly debated all over the nation, as other states considered adopting similar laws. In 1854, the Mississippi legislature banned the sale of liquors “in any quantity whatever, within five miles of said college,” referring to Mississippi College. In 1855, Ebenezer Baptist Church (Amite) granted permission to the ”sons of temperance” to build a “temperance hall” on land belonging to the church. In 1860, a member of Bethesda Baptist Church (Hinds) confessed he “had been selling ardent spirits by the gallon” and “acknowledged he had done wrong and would do so no more.” He was “requested by the church not to treat his friends with spiritous [sic] liquors when visiting his house.”

Frances E. Willard, one of the most famous temperance activists in the nation, spent a month in Mississippi in 1882 and announced, “Mississippi is the strongest of the Southern State W.C.T.U. organizations.” Every Baptist association had a temperance committee. T.J. Bailey, a Baptist minister, was the superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League. Prohibition of alcohol was such an emotionally charged issue that a liquor supporter assassinated Roderic D. Gambrell, son of Mississippi Baptist leader J.B. Gambrell and the editor of a temperance newspaper, The Sword and Shield. Nevertheless, the temperance movement was so successful that by 1897, all but five counties in Mississippi had outlawed the sale of liquor.

Book review: “Baptist Successionism: A Critical Review”

W. Morgan Patterson is a Southern Baptist historian, educated at Stetson University, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and Oxford University. This book was published in 1979, but I recently picked it up and read it in one day.

This is a concise book (four chapters, 75 pages) that analyzes the failures of the sloppy historical research of Baptists, such as Landmarkists, who believe Baptist churches are in a direct line of succession from New Testament times. The introduction explains there are four different variations of successionist writers, from those who believe they can demonstrate it and that is necessary, to those who believe neither. Chapter one explains how the successionist view was not that of the earliest Baptists, but in the 19th century it was formulated by G.H. Orchard and popularized by J.R. Graves. Chapter two shows how the successionist writers misused their sources. Chapter three shows their poor logic. Chapter four exams some of the motivations behind this erroneous view. The conclusion sums up the book, noting that the successionist view was predominant in the 19th century, but thanks to bold historians like William Whitsitt, whose research debunked the theory in the 1890s, the successionist view became a minority position among Baptist historians in the 20th century.

Patterson is scholarly historian, and he may assume a little too much about the historical knowledge of the reader when he refers to the Münster incident on page 22 without explaining that this was a violent takeover of the city of Münster, Germany in 1534 by an Anabaptist fringe group that came to be associated with Anabaptists and Baptists in the minds of their opponents, and he refers to the Whitsitt controversy on page 24 without explaining the controversy until later.

Patterson could have made his argument stronger by giving more specific details about the heretical beliefs of groups claimed by successionist writers to be Baptists, such as the Donatists, Paulicians, Cathari, etc.

While Patterson’s book is concise, it is substantive, and his reasons are sound. This is an effective critique.

Book Review: “Love Does” by Bob Goff

Bob Goff is a lawyer who loves the word “whimsy,” a word he uses constantly. His whimsical book starts each chapter by stating what he used to think and how he changed his mind (generally along the lines of how he used to think love was a feeling but now he thinks it is an action), followed by a whimsical true story from his life to illustrate his point. His stories are full of whimsical humor and talk about Jesus as his motivation for doing good deeds– and Goff does amazing deeds, particularly in Uganda, where he helped end injustice in the prison system and provided an education for countless children who were former fighters in the civil war.

His Christian motivation is inspiring, but his theology is shallow. He calls “missing the mark” a “stupid analogy” in chapter 16, and ridicules Bible teachers who use the term. One wonders if he even knows that “missing the mark” is the literal translation for the Greek word for sin, since in chapter 29 he ridicules people who study the Hebrew and Greek background of scripture.

Goff’s love in action is admirable– but his whimsy can be annoying if you value hard work and organization, such as when he tells how he got into law school by pestering the dean instead of doing the hard work to pass the entrance exam, and how he lied to get in a friend’s hotel room and ran up a $400 room service bill before the guy arrived as a “prank.” He describes many such adventures, never with a plan, but always with whimsy. He certainly gets a lot of good things done, but he swings the pendulum so far away from planning toward risk-taking that one wonders when one of his unplanned adventures will eventually cause some regrettable disaster. So far, so good– but I won’t risk reading any more of his books.

Spiritual equality of the races in antebellum Mississippi Baptist churches

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board

It may be surprising to modern readers to know that church minutes from Mississippi Baptist churches in the years before the Civil War gave every indication that while Black members were treated as unequal socially, they were treated as equal spiritually. That is, both Black and White members were received for baptism and by letter with the “right hand of Christian fellowship” and called “brother and sister,” and both Black and White members received church discipline.

In 1846, Hephzibah Church in Clarke County heard a report that a “colored sister Aggy” had “married a man who had a wife living.” They sent a committee to talk to her privately, and reported she confessed it was true but refused to change, so she was excluded from membership. However, in 1853 the same sister Aggy was repentant, forgiven, and restored to the fellowship of the church.

Bethesda Church in Hinds County had a special committee of five called, “the committee to wait on the blacks.” It was their duty to recommend any church discipline among Black members, as well as to recommend any Blacks who joined by experience of faith or church letter. This committee also invited “the widow Jones Peter to exhort the blacks when present.” In 1859, Bethesda Church charged a “Bro. J. T. Martin for striking with a stick and whipping a Negro boy of Bro. John H. Collins and against Bro. J. H. Collins prosecuting at law Bro. J.T. Martin and cultivating an unchristian spirit toward him.” A committee was sent to get the two men to reconcile, but when they refused, both men were excluded from membership. Apparently, the “committee to wait on the blacks” was made up of White members, and thus was patronizing and socially inequal; yet the very existence of the committee was a recognition of the spiritual value of all races, and their actions showed some genuine desire to protect Blacks such as the slave mentioned above.

In April of 1858, Ebenezer Church in Amite County investigated rumors that a member had killed a enslaved girl, but accepted testimony of two witnesses that her death was an accident. However, in December 1858, Ebenezer Church excluded a Peter A. Green because Green killed one of his escaped slaves when he apprehended him. This was an interesting case in which a White person was disciplined by an antebellum Mississippi Baptist church for killing a Black person. While the social inequalities allowed Green to escape murder charges, he did not escape the spiritual discipline of his church.

In no way am I implying that Blacks were treated as fully equal to Whites in Mississippi Baptist churches in the early 1800s. They were not given places of leadership and they were usually required to sit in a separate location from Whites. However, the evidence is strong that when it came to their spiritual value as brothers and sisters in Christ, Blacks were valued far more spiritually in the church than most modern readers would imagine.

SOURCES:

Minutes, Ebenezer Church, Amite County, April 17, 1858, December 18, 1858; Minutes, Bethesda Church, Hinds County, July 1849, October 1849, March 19, 1859, April 16, 1859; Minutes, Hephzibah Church, Clarke County, March 14, 1846, April 18, 1846; November 12, 1853.

Mississippi Baptist ministers to the Confederate Army during the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although not all white Baptists in Mississippi supported secession from the Union, they overwhelmingly supported the Confederate Army once the Civil War began. They especially felt the call to give spiritual support to the soldiers.

Mississippi’s legislature made ministers exempt from military service, but many of them volunteered for the military as chaplains, and others took up arms as soldiers. The Strong River Association sent two of their ministers to be chaplains in the Confederate Army: Rev. Cader Price to the Sixth regiment of the Mississippi Volunteers, and J. L. Chandler to the Thirty-Ninth.1 During this time, Baptist pastor H. H. Thompson served as a chaplain among the Confederate troops in southwest Mississippi. Thompson was the pastor of Sarepta Church in Franklin County, and simultaneously served as a chaplain to Confederate soldiers. In July 1862, Sarepta Church recorded in its minutes the resignation of Pastor Thompson due to poor health: “Resolved, that we accept the Bro. Thompson’s resignation but regret to part with him, as we found in him a faithful pastor, warm friend and devoted Christian, the cause of his resignation bad health. He has been laboring for some time under [handwriting illegible] and his service in the camps of the Army increased it to such extend that he sought medical advice which was that he should resign his pastoral labors.” 2

Chaplains actively proclaimed the gospel among the Confederate soldiers in Mississippi and Mississippians preached and heard the gospel as they fought in the war throughout the South. Matthew A. Dunn, a farmer from Liberty in Amite County, joined the State militia. From his military base in Meridian, Dunn wrote a letter to his wife in October 1863 that described nightly evangelistic meetings: “We are haveing [sic] an interesting meeting going on now at night—eight were Babtized [sic] last Sunday.” Sarepta Church in Franklin County recorded that a chaplain in the Confederate Army baptized one of their own who accepted Christ while on the warfront: “Thomas Cater having joined the Baptist Church whilst in the Confederate Army and have since died.” The certificate said he was baptized March 13, 1864, in Virginia by Chaplain Alexander A. Lomay, Chaplain, 16th Mississippi Regiment.3

One of the Confederate soldier/preachers would later become president of the Mississippi Baptist Convention and founder of Blue Mountain College. Mark Perrin Lowrey was a veteran of the Mexican War, then a brick mason who became a Baptist preacher in 1852. When the Civil War began, he was pastor of the Baptist churches at Ripley in Tippah County and Kossuth in Alcorn County. Like many of his neighbors in northeast Mississippi, he did not believe in slavery, yet he went to Corinth and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He was elected colonel and commanded the 32nd Mississippi Regiment. Lowrey commanded a brigade at the Battle of Perryville, where he was wounded. Most of his military career was in Hood’s campaign in Tennessee and fighting against Sherman in Georgia. He was promoted to brigadier-general after his bravery at Chickamauga, and played a key role in the Confederate victory at Missionary Ridge. In addition to fighting, he preached to his troops. One of his soldiers said he would “pray with them in his tent, preach to them in the camp and lead them in the thickest of the fight in the battle.” Another soldier said Lowrey “would preach like hell on Sunday and fight like the devil all week!” He was frequently referred to as the “fighting preacher of the Army of Tennessee.” He led in a revival among soldiers in Dalton, Georgia, and afterwards baptized 50 of his soldiers in a creek near the camp. After the war, the Mississippi Baptist Convention elected Lowrey president for ten years in a row, 1868-1877.4

First Baptist Church of Columbus, perhaps the most prosperous Baptist congregation in the State, lost many members to the war, and many wealthy members lost their fortunes. Their pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale, resigned the church in 1863 to become an evangelist among the Confederate troops. He often preached to an entire brigade, and in one case, preached a sermon on “The General Judgment” to 6,000 soldiers of General Claiborne in Dalton, Georgia, baptizing 80 soldiers after the sermon, and baptizing 60 more the next week. After the Union Army under Sherman attacked, he was no longer able to preach to the soldiers, and returned home to Columbus.5

NOTES:

1 John T. Christian, “A History of the Baptists of Mississippi,” Unpublished manuscript, 1924, 186; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1861, 13-16.

2 John K. Bettersworth, “The Home Front, 1861-1865,” in A History of Mississippi, vol. 1, ed. by Richard Aubrey McLemore (Hattiesburg: University & College Press of Misssissippi, 1973), 532-533; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, July 1862; Minutes, Bethesda Baptist Church, Hinds County, Mississippi, October 18, 1862.

3 Matthew A. Dunn to Virginia Dunn, October 13, 1863. Matthew A. Dunn and Family Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, October 1865.

4 Christian, 135, 197; Robbie Neal Sumrall, A Light on a Hill: A History of Blue Mountain College (Nashville: Benson Publishing Company, 1947), 6-12.

5 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 184-185.

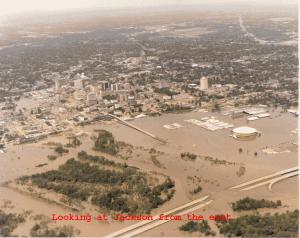

Mississippi Baptist responses to natural disasters in late 20th century

Article copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Hardly a year passed without a story of a natural disaster or fire destroying a church in Mississippi in the late 20th century, yet each time Baptists responded with a helping hand. Mississippi Baptists began to organize and prepare themselves to respond to disasters. Soon after Hurricane Camille in 1969, Southern Baptists began discussing a more efficient way to respond to disasters. The Mississippi Baptist Convention put together a van with supplies in the 1970s, and assigned the work to the Brotherhood Department.

The Pearl River “Easter Flood” shut down the city of Jackson in April 1979. Some 15,000 residents had to be evacuated by Thursday, April 17, and downtown was cordoned off. Although no Mississippi Baptist churches were flooded, the Baptist Building in Jackson had to close for a time. At least 500 Baptist families had flooded homes, particularly members of Colonial Heights, Broadmoor, First Baptist, Northminster and Woodland Hills Baptist churches. Several hundred male student volunteers from Mississippi College were bussed from their dorms in Clinton to Flowood to work on the levee. The Mississippi Baptist Disaster Relief van was on the scene, serving hot meals to 1,500 people. For weeks, volunteers met every Saturday to do repairs, and the MBCB executive committee endorsed a statewide offering for churches to aid in flood relief.1

Hurricane Frederic damaged churches in the Pascagoula area in September 1979. In September 1985, Hurricane Elena did damage estimated at $3 million to churches and Baptist facilities all over the Gulf Coast. Griffin Street Baptist Church in Moss Point had its back wall blown out. The pastor, Athens McNeil, quipped, “We’re open to the public… literally.” Elena also damaged Gulfshore Baptist Assembly, the seamen’s center, and it caused $1.5 million in damage to William Carey College on the Coast. Baptist relief units were on the scene right away, working in conjunction with the Red Cross. A number of Baptist churches served as shelters; some 250 people stayed at First Baptist Church, Pascagoula.2

A deadly tornado hit churches in Pike and Lincoln counties in January 1975, and another twister damaged churches in Water Valley in April 1984. The most destructive tornado during this time was the one that hit Jones County on Saturday, February 28, 1987. Five Baptist churches had property damage, and members of five other Baptist churches had personal property damage. “I have never seen such damage since I left the battlefield in Europe as I saw in Jones County,” wrote Don McGregor, editor of The Baptist Record. Immediately, the Mississippi Baptist Brotherhood Department began calling churches across the State for volunteers. The day after the Jones tornado hit, 325 volunteers, representing 55 churches, arrived at the Jones County Baptist Association to serve. Hundreds more volunteers arrived during the week; eventually 1,000 people helped with clean-up and relief supplies.3

SOURCES:

1 The Baptist Record, April 19, 1979, 1; April 26, 1979, 1; May 10, 1979, 1; May 17, 1979, 1; Author’s personal memory as a student at Mississippi College working on the levee for 17 hours in one day to stop floodwaters.

2 The Baptist Record, September 12, 1985, 3; September 20, 1979, 1; September 29, 1979, 1; September 19, 1985, 1, 3, 5.

3 The Baptist Record, January 16, 1975, 1, 2; March 5, 1987, 3; March 12, 1987, 3, 4; March 19, 1987, 2.

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a history of Mississippi Baptists.

Comparing abortion rights to slaveholder rights

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

When the Supreme Court Dobbs decision of 2022 returned to the States the authority to decide their own policies on abortion, many observers noted that the last time we had such division among the United States was when we had “free” and “slave” States. Of course, both pro-life and pro-abortion leaders prefer to identify themselves with the “free” States.

The historical reality is that back then, both sides also saw themselves on the side of protecting their rights. Abolitionists wanted to protect the rights of slaves to be free, but slaveholders saw themselves as defending their rights to own slaves.

When Mississippi seceded from the Union, it published “A Declaration of Independence” which framed slave ownership in much the same way as modern abortion rights activists frame their claim to a right to abortion. Mississippi complained of how the abolitionist movement endangered their rights, saying, “it denies the right of property in slaves and refuses protection to that right… It has recently obtained control of the Government…We must either submit to degradation, and to loss of property worth four billions of money, or we must secede from the Union.”

Like it or not, slaveholders saw themselves as victims of having their rights stripped away. Even some of their Northern friends saw it that way. When Francis Wayland of Rhode Island wrote to slaveholders in the South, he said, “You will separate of course. I could not ask otherwise. Your rights have been infringed.”

The truth is that anybody can demand their rights; the real question is which right is greater. The so-called “right” to hold somebody in slavery violated the human right of that slave. Those who desire a right to abortion loudly shout, “My body, my choice.” However, the babies in the womb are unable to speak up about their bodies; they have no choice, unless somebody speaks up for their right to life. We must ask ourselves, which right is more important?

Rev. T. C. Teasdale’s daring adventure with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most amazing but lesser-known stories of the Civil War is how a Mississippi Baptist preacher got both Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln to agree to help him sell cotton across enemy lines in order to fund an orphanage. Although the plan collapsed in the end, the story is still fascinating.

Since over 5,000 children of Mississippi Confederate soldiers were left fatherless, an interdenominational movement started in 1864 to establish a home for them. On October 26, 1864, the Mississippi Baptist Convention accepted responsibility for the project. The Orphans’ Home of Mississippi opened in October 1866 at Lauderdale, after considerable effort, especially by one prominent pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale.1

Rev. Teasdale was in a unique position to aid the Orphans’ Home, because of his influential contacts in both the North and South. A New Jersey native, he came to First Baptist Church, Columbus, Mississippi in the 1850s from a church in Washington, D.C. When the Civil War erupted, he left his church to preach to Confederate troops in the field. In early 1865, he returned from preaching among Confederate soldiers to assist with the establishment of the Orphans’ Home of Mississippi. He launched a creative and bold plan to raise money and solve a problem of donations. A large donation of cotton was offered to the orphanage, and the cotton could bring 16 times more money in New York than in Mississippi, but how could they sell it in New York with the war still raging? Since Teasdale had been a pastor in Springfield, Illinois and Washington, D.C. and had preached to the Confederate armies, he was personally acquainted with both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln (from Illinois) and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and many of their advisers. In February and March 1865, he set out on a dangerous journey by horseback, boat, railroads, stagecoach and foot, dodging Sherman’s march through Georgia, crossing through the lines of the armies of both sides, and conferred in Richmond and Washington, seeking permission from both sides to sell the cotton in New York for the benefit of the orphanage.2

Confederate President Davis readily agreed, and on March 3, 1865, Davis signed the paper granting permission for the sale. Next, Dr. Teasdale slipped across enemy lines and entered Washington, a city he knew well, since he was a former pastor in the city. He waited in line for several days for an audience with President Lincoln, but he could not get in, since government officials in line were always a higher priority than a private citizen. Finally, he sent a note to Mr. Lincoln, whom he knew when they both lived in Springfield, Illinois, saying that he was now a resident of Mississippi and that he was there on a mission of mercy. Lincoln received him, and he listened to the plea for cotton sales to support the orphanage, but the president was skeptical. Why should he help Mississippi, a State in rebellion against the United States? In his autobiography, Teasdale records Lincoln’s words: “We want to bring you rebels into such straits, that you will be willing to give up this wicked rebellion.” Dr. Teasdale replied, “Mr. President, if it were the big people alone that were concerned in this matter, I should not be here, sir. They might fight it out to the bitter end, without my pleading for their relief. But sir, when it is the hapless little ones that are involved in this suffering, who, of course, who had nothing to do with bringing about the present unhappy conflict between the sections, I think it is a very different case, and one deserving of sympathy and commiseration.” Lincoln instantly said, “That is true; and I must do something for you.” With that, Lincoln signed the paper, granting permission for the sale. It was March 18, 1865. However, a few weeks later, on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army to Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant. By the time Teasdale returned home, the war was over, the permission granted by Jefferson Davis no longer had authority, Lincoln was assassinated, and Teasdale abandoned his plans. Teasdale said, “This splendid arrangement failed, only because it was undertaken a little too late.” Undaunted, Dr. Teasdale volunteered as a fundraising agent for the orphanage and staked his large private fortune on its success. Rarely has there been a more daring donor to a Christian cause!3

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 12-17; 1867, 29-31.

2 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists in Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 131.

3 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 173-174, 187-203; Boyd, 130-132; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 14-16.

Prayer for a servant attitude

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

Lord, forgive me when I make my encounters with others all about myself.

You said that You came not to be served, but to serve and give Your life a ransom for many (Mark 10:45). Teach me not to tell my story before listening to the stories of others. Teach me not to pray for myself until I have prayed for others. Teach me not to grab a gift for myself until I have handed a gift to others. May I never use other people for my ends, but rather, may I give away my life for their good. In Jesus’ Name. Amen.

The Lord’s Prayer, Revisited

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

After this manner therefore pray – Matthew 6:9, KJV. Jesus did not command us to pray the Lord’s Prayer literally, as He worded it. Rather, He said to pray “after this manner,” or “like this.” In other words, He gave it as a model prayer for us to pray in our own words. Inspired by that thought, I revisited the prayer to write my own prayer “after this manner,” seeking to express His words in my own words. Here is my attempt. May it nudge you to be fresh and sincere as you pray the Model Prayer.

God, You are our intimate Father

Yet You are the transcendent Holy One.

Since You are King in heaven,

May we submit to your Lordship on earth.

We need your physical gift of food,

We need your spiritual gift of forgiveness,

And we need your social gift of grace to forgive others.

Take us by the hand, and lead us away

Far from the devil, that we may not stray.

We crown You, we submit to You, we honor You forever.

Amen.

A prayer to experience God’s presence

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

O God of the universe, I want to experience Your presence. You spoke to Moses in a burning bush, and spoke to Elijah in a still, small voice. You called Samuel from his bed during the night, and You called Paul in broad daylight on the road to Damascus. Teach me to look for You in things great and small, day and night. I want to hear from You when I read Your word, and when I hear a child share a simple truth. I want to see You in the lightning across the sky, and in the smile of a new friend. I want to feel You when I sing in the sanctuary and when I hug someone in pain. May I experience Your presence, and pass on that experience to those I meet this day. In the name of the One who walked on water, yet needed someone to wash his dirty feet, Jesus Christ my Lord.

Prayer when life seems out of control

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

O Lord, I feel like my life is out of control, floating down a river, and I can’t see what’s ahead. I run into sudden rocks, reptiles and rapids, and then a right-angle bend in the river. I try to navigate my raft, but I realize that I have to trust the swift currents of Your grace. I believe that even as the sun sets over the water and I float into the unseen future, the sun will rise tomorrow over the gulf of Your goodness. Thus I will take this day as an adventure with God as my guide. In Jesus’ Name, Amen.