Prayer for guidance in the culture wars

(Below is a prayer written by my colleague and fellow hospital chaplain, Vance Moore. It is shared with his permission.)

So it is with Christ’s body. We are many parts of one body, and we all belong to each other. – Romans 12:5

Our Father,

Daily we are faced with culture wars: liberal beliefs, conservative beliefs, and it seems everyone has a unique worldview or ideology. Even in our churches, we are divided. While scriptures tell us we are “one in Christ,” we continue to separate ourselves along the line and issues which are important to us. Your word is clear that we are to be one with You and keep our “eye on the prize.” Help us, Father, to align ourselves with the only worldview/ideology that is acceptable in Your sight. Keep us vigilant and moving toward the only worhty goal– of our relationship with You. Bless us and bless our service this day.

In Christ’s name we pray, Amen.

Prayer of thanks for the extraordinary ordinary

Our mouths were filled with laughter then, and our tongues with shouts of joy. – Psalm 126:2, CSB

Lord, I am so blessed. My lips can kiss my wife each morning when I get up and each evening when I go to bed, and I am grateful. Lord, my hands are able to work and provide for my family, and I am thankful. My mouth is filled with a delicious meal, and I am grateful. My tongue shouts when my team hits a home run, and I am thankful. My ears can here the flowing rivers, my nose can smell the fragrant flowers, and my eyes can see the fertile forests, and I am grateful. My head is covered with a safe shelter each night when I go home, and I am thankful. My knees hit the floor each morning and each night in prayer to You, the source of the extraordinary in the ordinary, and I am grateful.

Mississippi Baptist church discipline in the 19th century

During the 19th century, Baptist churches in Mississippi maintained strict discipline over their members. Henry Nichols was excluded from Sarepta Church in Union Association “for drawing his knife and offering to stab his brother and for spitting in his face.” Benjamin Brown was excluded from Ebenezer Church in Amite County for “attending a horse race and wagering thereon.” James Dermaid was excluded from Providence Church in what is now Forrest County “for “disputing, quarreling, and using profane language, and absenting himself from the church.” Providence Church also excluded “brother Alexander Williams and sister Leuizer Maclimore upon a charge of their attempting to go off and cohabit together as man and wife.” In 1828, the African Church at Bayou Pierre had a query for Union Association: “Is it gospel order for a Baptist church to hold members in fellowship who have married relations nearer than cousins?” The association answered that it was not. Jane Scarborough, wife of Rev. Lawrence Scarborough of Sarepta Church accused “Sister Harris” of being drunk at a wedding and for hosting “Negro balls” (debutante balls for blacks). Instead, the church charged Mrs. Scarborough of gossip without evidence, and excluded her for making the accusations!1

Mississippi Baptists moved gradually from a policy of tolerating mild use of alcohol, toward a policy of complete abstinence from alcohol. A Committee on Temperance made an enthusiastic report to the Mississippi Baptist Convention in 1838 of “the steady progress of the Temperance Reformation in different parts of Mississippi and Louisiana; prejudices and opposition are fasting melting away.” In 1839, D. B. Crawford gave a report to the Convention on temperance which stated, “That notwithstanding, a few years since, the greater portion of our beloved and fast growing state, was under the influence of the habitual use of that liquid fire, which in its nature is so well calculated to ruin the fortunes, the lives and the souls of men, and spread devastation and ruin over the whole of our land; yet we rejoice to learn, that the cause of temperance is steadily advancing in the different parts of our State.” Local churches consistently disciplined members for drunkenness, but they were slower to oppose the sale or use of alcohol. For example, in May 1844, “a query was proposed” at Providence Church in Pearl River Association on the issue of distributing alcohol. After discussion, the church took a vote on its opposition to “members of this church retailing or trafficking in Spirituous Liquors.” It is significant that in the handwritten church minutes, the clerk wrote that the motion “unanimously carried in opposition,” but then crossed out the word “unanimously.” In January 1845, Providence Church voted that “the voice of the church be taken to reconsider” the matter of liquor. The motion passed, but then tabled the issue, and did not come back up. In March of that year, a member acknowledged his “excessive use of arden[t] spirits” and his acknowledgement was accepted, and he was “exonerated.”2

The Mississippi Baptist Convention heard frequent reports on how to defend against desecrations of the Sabbath. In 1840, M. W. Chrestman reported, “The Sabbath, or Lord’s Day, is an institution of Divine Origin, and is therefore of universal obligation… On the Lord’s Day all manner of servile labor is positively prohibited, with the exception of works of necessity and mercy… Every necessary arrangement and sacrifice should be made; every carnal pleasure and sensual gratification should be denied… Resolved, That we recommend that our ministering brethren with greater zeal and diligence explain and enforce the proper observance of the Lord’s Day.” Local Mississippi Baptist churches considered violation of the Sabbath a serious matter. In March 1837, William Dossett, a member of Providence Church in what is now Forrest County, confessed to the church “that he had been hunting a deer on the Sabbath, which he had wounded on the preceding evening.” After “considerable discussion of the subject,” the church was satisfied with his explanation.3

SOURCES (All available at the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission Archives, Leland Speed Library, Mississippi College, Clinton, Mississippi):

1 Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Jefferson County, Mississippi, August 1815, June 1828, July 1828; Minutes, Ebenezer Baptist Church, Amite County, Mississippi, February 6, 1813; March 6, 1813; Minutes, Providence Baptist Church, Forrest County, Mississippi, December 10, 1842, September 2, 1843; Minutes, Union Baptist Association, 1828.

2 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1838, 1839; Minutes, Providence Baptist Church, Forrest County, Mississippi, May 11, 1844, January 11, 1845, March 8, 1845.

3 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1840; Minutes, Providence Baptist Church, Forrest County, Mississippi, March 4, 1837.

Breaking news: LifeWay to republish the Holman Christian Standard Bible

It’s not official yet, but as the administrator of the Facebook fan page for the Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB), I have been privy to some internal discussions from editors of LifeWay and Holman Bible Publishers, who have quietly been considering republishing a print edition of the HCSB.

The HCSB was first published in 2004 by Holman Bible Publishers, but discontinued in 2017 in favor of the Christian Standard Bible (CSB). When first published, the HCSB won praise among evangelicals for being more accurate than the popular New International Version (NIV), yet more readable than the reliable New American Standard Bible (NASB). However, it received some criticism for some unusual characteristics, such as occasionally using the literal “Yahweh” for the Old Testament name of God (traditionally translated with all capital letters, LORD), and for taking non-traditional translations, such as interpreting “sixth hour” in John 4:6 to mean that Jesus met the woman at the well at 6:00 in the evening, rather than the sixth hour of the day, at noon. The awkward name, Holman Christian Standard Bible, was also ridiculed by some as the Hard Core Southern Baptist translation, as Holman is owned by LifeWay Christian Resources of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Thus in 2017, Holman Bible Publishers made a major revision of the HCSB, keeping most of the language but removing most of the non-traditional elements of the HCSB, and gave it a simpler name: Christian Standard Bible (CSB). The CSB was released in 2017, and Holman discontinued printing the HCSB, although digital versions were still available on platforms such as YouVersion and Olive Tree Bible app. Holman Publishers hoped to market the CSB to a larger audience, and they did. The CSB consistently ranks in fifth place among purchases of new Bibles, according to ECPA.

However, there remained a faithful and loyal group of people who preferred the HCSB. As the administrator of the Facebook group dedicated to the HCSB, I know. And since I am the administrator, LifeWay CEO Ben Mandrell contacted me recently to discuss the interest in making a simple leatherflex print edition of the HCSB available, as a test market. He emphasized that they are still committed to the CSB, but thought there might stll be a niche market for the HCSB, just as some people prefer older editions of the NASB.

If you are interested in a print edition of the HCSB, do not contact Holman Bible Publishers or LifeWay, because they will not know what you are talking about, since this is an April Fool’s joke.

The first Mississippi Baptist associations and state convention

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

In Mississippi, five of the six Baptist churches organized the Mississippi Baptist Association in 1807, with a total of 196 members. By 1819, the Mississippi Association had 41 churches and more than 1,125 members. The association covered the entire 14-county area of Mississippi that was settled at that time. This prompted the formation of two new associations in 1820, the Union Association and the Pearl River Association.1

Eight churches from Mississippi Association organized the Union Association in September, 1820 at Bayou Pierre church near Port Gibson, including the mother church, Salem, and the church in the largest town, Natchez. Prominent leaders of the Union Association included David Cooper, D. McCall, L. Scarborough, John Burch, Elisha Flowers and Nathaniel Perkins. One of its first actions was to create a fund for traveling preachers, and “Brother John Smith is requested to travel for one year, and preach the gospel, as our missionary, through the state.” For this mission work, they paid him $10.2

The same year, the Pearl River Association organized at Fair River Church in November, 1820, with 23 churches, which included 14 churches from Mississippi Association, as well as other churches that had never been in an association. Located east of the Pearl River in southeast Mississippi, this was a rapidly growing section of the State. By 1836, there were 33 churches and 982 members in Pearl River Association. Among its new churches was an African church. The first moderator and prominent leader of this association was Norvell Robertson, Sr., pastor of Providence Church, founded in 1818 a few miles north of the location of the future city of Hattiesburg.3

A national organization of Baptists, commonly called the Triennial Convention, was organized in 1814, as a society to support foreign missions. This sparked many States to also organize conventions, including Mississippi in 1823.4

In 1823, the Pearl River Association invited the other two associations in the State to form a Baptist state convention. Both associations accepted the invitation. The Mississippi Baptist State Convention was organized at Bogue Chitto Church in Pike County in February, 1824. A constitution was written, and the second session was held the same year, in November, 1824 at East Fork Church, Amite County. Dr. David Cooper was elected president, and officers were elected representing each of the associations. However, it disbanded in 1829. I will share that story in a later post.5

SOURCES:

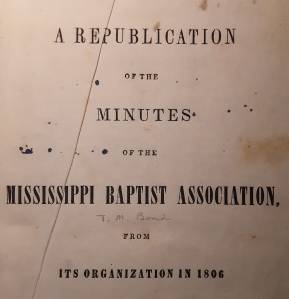

1 T. M. Bond, A Republican of the Minutes of the Mississippi Baptist Association (New Orleans: Hinton & Co., 1849), 70; 264.

2 Leavell and Bailey, A Complete History of Mississippi Baptists from the Earliest Times, 2 vols., (Jackson, 1903), I, 72-74; Minutes, Union Baptist Association, 1842. The minutes of 1842 was citing from the original minutes of September 18, 1820, noting the 1820 minutes were “worth preserving” since the 1820 minutes were already “very scarce” in 1842.

3 Minutes, Pearl River Baptist Association, 1820, 1836.

4 Richard Furman, “Address at Formation of the Triennial Convention,” Proceedings of the Baptist Convention for Missionary Purposes (Philadelphia, n.p., 1814), 38-43; Jesse L. Boyd, A History of Baptists in America Prior to 1845, (New York, 1957), 186.

5 Leavell and Bailey, I, 134-135; Bond, 84; Minutes, Pearl River Association, 1824; The Second Annual Report of the Mississippi Baptist State Convention in Session at East Fork Church, Amite County, Nov. 12th and 13th, 1824 (Natchez, 1825).

Prayer for the new day

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

Lord, this is a new day, the day You have made. Please go before me and lead me. At some point today, I will meet people and circumstances that I did not expect, but You will not be caught by surprise. So keep my eyes and ears open to what You are doing around me, that I may join You in Your work. In Jesus’ Name I pray. Amen.

Prayer for wisdom in suffering

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

Precious Lord Jesus, I want to know the power of Your resurrection, and the fellowship of Your suffering (Philippians 3:10). When I am weak, help me draw strength from You. When people insult me, remind me that that they hurled insults at You. Give me grace not to slander, but give me courage to speak the truth. If I suffer for doing right, give me peace. If I suffer for my own sin, give me the courage to repent. In all things, give me the wisdom to know the difference.

The first Baptist missions to Native Americans in Mississippi

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Native Americans were an area of concern for Mississippi Baptists. The white man wanted the Indian lands, and but the Baptists desired the conversion of their souls. In 1817, the Mississippi Baptist Association began an aggressive policy by sending Thomas Mercer and Benjamin Davis to visit the Creek Indians and see what cold be done to establish the gospel among them. The missionaries started out on their mission, but the project collapsed when Mercer died. Baptists in Kentucky started an academy for Choctaws in that State in 1819, but it closed in 1821. Richard Johnson, a Baptist leader in Kentucky, then opened an academy for Mississippi Choctaws in 1825 in the district of Choctaw chief Mushulatubbee, which was approximately the area between the modern cities of Columbus and Meridian. This school’s curriculum was secular, but the teachers hoped to “civilize” the Choctaws and lead them to faith in Christ. They met with some success among students, but the missionaries had little impact on adults in the tribe. A young female student wrote: “I do not know that one adult Choctaw has become a Christian. We all pray for them, but we cannot save them; and if they die where will they go? May the Lord pour out his Spirit upon the poor Choctaw people.” It would be many years before missions to the Choctaw tribe would have much impact.

This is one in a series of blog posts about Mississippi Baptist history. Click the links on this blog to read other posts on Mississippi Baptist history. More stories to come.

(Source: T. M. Bond, A Republication of the Minutes of the Mississippi Baptist Association (New Orleans: Hinton & Co., 1849), 60, 71; Clara Sue Kidwell, Choctaws and Missionaries in Mississippi, 1818-1918 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995), 100-113.)

How 19th century Mississippi Baptists viewed slavery

Article copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board

White Mississippi Baptists received African slaves into their churches as fellow members, and worshiped with them, but how did they view the “peculiar institution” of slavery itself? The “African Baptist Church” was a church made up of slaves that met on Bayou Pierre, a river near Port Gibson, beginning in the 1810s. The congregation was a member of the Mississippi Baptist Association. In 1814, the Mississippi Baptist Association received the letter from the African Church, stating “their case and the many difficulties they labor under.” The Association instructed the church “to use their utmost diligence in obeying their masters, and that prior to their assembling together for worship, they be careful to obtain a written permission from their masters or overseers.” The Association also expressed its “anxious wish” that “the ministering brethren” of the Association would serve them and preach to them. In 1815, Carter Tarrant, an anti-slavery Baptist preacher from Kentucky, and member of the anti-slavery organization, Friends of Humanity, was a guest preacher at the Mississippi Baptist Association. In 1806, Tarrant had published a sermon against slavery, insisting it was the essence of hypocrisy to sign the Bill of Rights and consign blacks to bondage. The words of his sermon at the Mississippi Association are not recorded.

In 1819, a committee of David Cooper, James A. Ranaldson and William Snodgrass composed the circular letter from the Mississippi Baptist Association to all the churches, on the subject of “Duty of Masters and Servants.” It began by stating approval of social rank in society: “In the order of Divine Providence… God has given to some the pre-eminence over others.” It cited examples of masters and servants in scripture as evidence of this. Then they offered advice to masters. Quoting Colossians 4:1 and Leviticus 25:43, they told masters to “be just in your treatment,” and warned masters against expecting labor from slave that they were unable to do, because it “would be cruel and unjust.” They also told slaveowners that they were obligated to show kindness and compassion. Third, they said it was the “duty” of masters not only to care for the physical bodies of slaves, “but more especially that of their souls.” The letter then turned its attention to servants, noting “as many of them are members of our churches” (it is notable that the letter did not refer to many slaveowners as being members). Addressing slaves as “brethren,” the letter acknowledged that being enslaved was “dark, mysterious and unpleasant,” yet claimed the institution had been “founded in wisdom and goodness.” The letter took the statement about Christ’s atonement in 1 Corinthians 6:19-20 and implied that it referred to their purchase as slaves: “Remember you are not your own; you have been bought with a price, and your master is entitled to your best services… You must obey your earthly master with fear and trembling, whether they are perverse and wicked, or pious and gentle.” The letter quoted numerous scriptures instructing slaves to obey their masters (Ephesians 6:5-7, Titus 2:9-10, 1 Peter 2:18 and 1 Timothy 6:1-2), while omitting passages against slavery, such as Exodus 21:16, Deuteronomy 23:15-16, Philemon 1:15-16 and 1 Timothy 1:10. This circular letter was typical of how most white Southerners viewed slavery in the antebellum period. White Baptists in Mississippi and across the Deep South spoke publicly against abusive treatment of slaves, but in actual practice, they did not intervene to prevent it. While Baptist church minutes frequently recorded discipline of members for drinking, gambling, and other moral failures, they rarely record discipline of slaveowners for mistreating slaves.

(Sources: T.M. Bond, A Republication of the Minutes of the Mississippi Baptist Association (New Orleans: Hinton & Co., 1849), 42, 48, 72-74; Aaron Menikoff, Politics and Piety: Baptist Social Reform in America, 1770-1860 (Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2014), 93-94; Carter Tarrant, The Substance of a Discourse Delivered in the Town of Versailles (Lexington, KY: D. Bradford, 1806), 25-27. There were a few examples of Baptists in the South who opposed slavery, such as John Leland who led Virginia Baptists to speak publicly against slavery in the 1790s, and David Barrow in Kentucky, who wrote a pamphlet against slavery in 1808 . Carter Tarrant, who preached at the Mississippi Baptist Association in 1815, joined David Barrow in the anti-slavery organization, Friends of Humanity.)

The first African-American Baptists in Mississippi

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

From the start, many of the Baptists of Mississippi were African-American. Only a few of the white Baptists owned slaves, but slaves who belonged to non-Baptist slaveowners were welcomed to worship as fellow members alongside whites in Baptist churches. From 1806 to 1813, Ebenezer Baptist in Amite County listed four “Africans” who joined, out of about 50 members. For instance, on December 8, 1815, the minutes of Ebenezer read, “Received by experience an African Ben belonging to Samuel Harrell.” (Samuel Harrell does not appear in the list of church members.) In 1821, Salem Baptist on Cole’s Creek had 28 white members, listed by full name, and 32 “black” members, listed by first name only, under the names of their owners. None of the slaveowners were members of the Salem church. The common practice was for slaveowners to give a written pass for slaves to attend worship. For example, the minutes at Salem on May 3, 1816 read, “Captain Doherty’s Phil came forward with his master’s written permission to join the church by experience.” (Doherty was not a member of the church.) Although slaves were bought and sold and transported from state to state, Baptist churches still received them by letter from their former churches. In November 1816, the minutes of Sarepta Church in Franklin County read, “Bob & Ferrby servants of Walter Sellers presented letters from Cape Fear Church in N. Carolina & was received.” Slave members were disciplined, as well, as Sarepta minutes of December 1822 read, “Bro. Prather’s Rose (a servant) excluded by taking that which was not her own.” From this wording, it is likely that Walter Sellers was a slaveowner but not a Baptist, whereas “Bro. Prather” likely was a member of the Sarepta church, who had a slave named Rose.

During the antebellum era until the end of slavery, most African-Americans worshiped with whites. However, there were a few Baptist churches that were exclusively for blacks. One such church was in the Mississippi Association. Called the “African Church,” it first appeared in the minutes of the association as a member church in 1813. It met at a sawmill belonging to Josiah Flowers, pastor of Bayou Pierre Church. In 1814, the African Church sent a letter to the association, and in 1815 the association called on the various white pastors to take turns preaching to the African Church, which was then using the meeting house of Bayou Pierre church. Every year from 1816-1819, the African Church sent two messengers to the associational meeting, by the names of Levi Thompson, Hezekiah Harmon (messenger twice), E. Flower (messenger three times), William Cox, S. Goodwin, J. Flower and W. Breazeale. They never appeared in the associational minutes in any leadership position, but they did attend as duly registered representatives of the African Church, and they were given a seat alongside their white brothers in Christ. There were other African churches, as well. In 1818, members of Bogue Chitto Church granted “the Request of the Black Brethren to be constituted into a church.” In 1822, members of Zion Hill Church in Mississippi Association considered licensing Smart, a slave, to “exercise his gift” to preach, but delayed their decision “in consequences of an Act passed in the legislature.”

The situation had suddenly changed. Fearing a slave insurrection, the new state of Mississippi’s legislature enacted a law prohibiting slaves or even free people of color from assembling except under certain restricted conditions. This brought the Mississippi Baptist Association into conflict with the state legislature. When the law was applied to the African church, it forced them to discontinue meeting for a time. The association took up the cause of the African church and appointed a committee to prepare a memorial to be “laid before the next legislature of this State, praying the repeal of such parts of a state law thereof, as deprives the African churches, under the patronage of this association, of their religious privileges and that Elder S. Marsh wait on the legislature with said memorial.” The legislature did not agree with the association, and the African stopped meeting for a time, although the members were still welcome in the other churches led by whites.

In 1824, the state legislature heeded the complaints of the churches, and revised the code to permit slaves to preach to other slaves, as long as the service was overseen by a white minister or attended by at least two white people appointed by the white church. Thanks to this revision in the law, African churches could meet again, and in 1826, Zion Hill Church allowed Smart to preach. The African Church at Bayou Pierre joined the new Union Association after 1820, meeting as a separate congregation from Bayou Pierre church. In 1828, the African Church reported 75 members (its sponsor church at Bayou Pierre had 48 members). The African Church was tied with Clear Creek Church in Adams County for the largest church in the association.

Ukrainian Baptist leader speech to his churches

Speech by Valery Antonyuk (President of the Evangelical Baptist Union of Ukraine)

to ministers and churches on the occasion of war. (Translated into English.)

You can view his speech in Ukrainian on YouTube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dCKqC8NNpPQ

Dear brothers and sisters, Church Ministers!

This morning, February 24, the war in Ukraine began. What we prayed would not happen happened today. And we, as believers, accept that we will have to go through the time of this trial.

The Bible says: “The Lord is my shepherd I shall not want. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil,for you are with me,your rod and your staff will comfort me”

That is why we urge everyone to continue and intensify our prayers.

This is our weapon in time of war, our way of fighting. This is the first thing believers do. And we invite everyone, wherever you are, to seek the opportunity to do this in person, in your families, in your churches, on ZOOM, wherever possible, gather together and praise the Lord.

Secondly, it’s important that the Lord gives us His peace right now and that we don’t panic, fear, reckless actions, sudden decisions that can harm us personally and our min hysteria in the ukraine.

We invite all Church ministers in these first days to give a message of hope through God’s Word to all the faithful who have to stand in this gap today and pray for our country. We need to strengthen this time with fasting and prayer because this is the time the Church continues to minister.

We say to all Church ministers, elders, deacons: think about how to maintain hospitality in your church premises, in your headquarters, where you have the opportunity to receive people in need. People moving around Ukraine today and will be targeted, especially along the border areas. Please, it is important for us to organize ourselves so that we can accommodate people in need.

We have many unanswered questions and only by moving step by step can we figure out where we can take the next step. Therefore, we ask that we can organize this at the church level. Our communities must become centers of service, shelters, for our people in times of adversity.

We ask all Christians not to spread unverified information, but to share the information that you witness and know exactly the authenticity, to turn it into an occasion of information, testimony and prayer.

We also pray for the organization of our coordination center, because in the office here near Kiev, we continue to serve and organize all the work even now. We will get in touch with all associations and coordinate in time all those processes that will prove to be important for all the Ukrainian people.

We’ll keep you updated on the situation. From time to time, we will make such calls, report on the current situation, and pray that we will all be together, united in what the Lord is doing.

We believe that God, even through us, wants His Kingdom of peace to spread today, even in times of war. We pray for the protection of our country and firmly believe that God will bless Ukraine!

Therefore, let’s unite together, we serve even in these conditions. We begin a new phase, a new page of ministry that has never been written before. God who has blessed us by making us live peacefully and serenely for decades, but in this time our whole country needs a church that is the light and salt. The Lord is our shepherd, we shall not want and he will guide us even in these moments.

God bless us as we pray for you as we serve the Lord together.

Prayer for God’s presence

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

Heavenly Father, I come before You in silence, my hands turned upward to You, my heart listening for Your voice. I take a deep breath; slowly I let it out. I want to inhale Your presence; I want to exhale distractions. I breathe in Your mercy and peace. I breathe out sin and shame. Jesus, I embrace Your grace. Drench me from head to toe with Your Spirit. As I go through this day, make me continually mindful of Your continual presence, and may I be a different man because the God-man dwells within.

The Mississippi Baptist revival during the War of 1812

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

On December 16, 1811, the New Madrid earthquake, with its epicenter in New Madrid in southeast Missouri Territory, was felt over a million square miles, including Natchez, where clocks stopped, houses were damaged, and the river rose and fell rapidly. A New Orleans writer said, “the shake which the Natchezians have felt may be a mysterious visitation from the Author of all nature, on them for their sins.” It would seem that many people were truly shaken to their core, not only by the earthquake, but also the War of 1812. The United States declared war on Great Britain in June 1812. In Mississippi the focus of the conflict was on the Indian tribes, especially the Creeks, who were supported by the British. In 1813, the Creeks attacked Fort Mims, north of Mobile, and massacred at least 250 people. The Creeks were eventually crushed by an army under General Andrew Jackson, but these dramatic events shook the souls of Mississippians. The annual Circular Letter of the Mississippi Baptist Association of October 1813, was on the subject of “The War.” It was a circular letter received from Ocmulgee Association in Georgia, republished with edits made by Mississippi pastors Ezra Courtney and Moses Hadley, because of “the distressed situation of our territory, and the nation in general.” It warned readers that perhaps “Divine Providence” had allowed Europe to “invade our rights” because of “our ingratitude, our avarice, and abuse of the rich blessings we have enjoyed.” It declared the war to be “a war of just and necessary defence [sic]; justifiable on every sound political and moral principle.” It called for unity to defend “the rich inheritance of freedom we possess,” and stressed how American liberty was unlike that of France, which had fallen into ungodly apostasy and lost its freedoms. “If history ever proved any one truth clearly, it is this: that no nation, without public and private virtue, ever retained its freedom long.” The message was clear: their freedoms were in danger, and if they wanted to keep their freedoms, Mississippians needed a fervent devotion to both God and country. It is not known how many people in the town of Natchez were shaken from their sins, but we do know that the territory experienced a religious revival. In 1813, 246 people were baptized into membership in the churches of the Mississippi Baptist Association, far more than any year in the decade before or after, and the total membership nearly doubled that year, from 494 to 914!

The hardest prayer to pray

(Few of us want to pray a prayer of confession. And when we do confess, we may say, “Lord, if I have sinned” (God knows we have!) or we soft-sell it with some safe sin, like, “Lord, I know I ran a red light” (He knows a lot worse things than that!) Our confession is rarely raw, vulnerable or gut-wrenching. But Biblical confesssion is brutally honest. So is this prayer, based on Psalm 38. Confession is the hardest prayer to pray, but in the end, it is the most rewarding. Copyright by Bob Rogers).

Lord, my sin is too much for me to bear! I feel the weight of my sin all the more as Your punishment presses down on me. My sin stinks like a festering wound, and my stomach turns at the smell of my foolishness. It hurts that my wrongdoing caused my loved ones and friends to stand back from me, and my enemies have used it to attack me, but it hurts even more, that I feel the pain of separation from You. I know that nothing is hidden from You. Knowing that You see my wicked heart and deceitful mind causes my skin to crawl and my heart to ache. So I confess my sin; I make no excuses; it troubles me; I am disgusted by what I have done. I trust in You, Lord, to forgive me and save me. Lord, do not leave me; hurry to help me, for You are my Savior and my only hope for forgiveness.