Blog Archives

The chaotic 1930 special session of the Miss. Baptist Convention

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

On July 15, 1930, an unprecedented second special session of the Mississippi Baptist Convention met in Newton, attended by 318 messengers. It turned into chaos.

(A first special session had been held in April to respond to the problems of the Great Depression by closing Clarke College and moving the Mississippi Baptist Orphanage to the campus of Clarke; however, some legal matters were not handled, so a second special session was called.)

This second special session erupted into a chaotic state of confusion, described by The Baptist Record as featuring “unanimous disagreement, often vociferously expressed.” MBCB executive R.B. Gunter made a plea for harmony, but it went unheard. W.N. Taylor of Clinton presented resolutions to continue Clarke College and keep the orphanage near Jackson, in effect to rescind the vote of the previous session. Convention president Gates ruled the resolutions out of order, but a challenge was made to his ruling; the messengers voted 164-154 to sustain his ruling. Next, M.P. Love of Hattiesburg moved that the property of the orphanage be mortgaged to pay the debts of Clarke College, but his resolutions were voted down. At a stalemate, the messengers then adjourned to dinner.

The Baptist Record commented that the only thing the messengers agreed about was that “the people of Newton and vicinity furnished a good dinner.” After dinner, the messengers returned and reversed their earlier actions. This time, Gates’ ruling was overturned. Next, the messengers adopted Taylor’s resolutions, voting to keep the orphanage in Jackson and to re-open Clarke College. To pay for it, the messengers authorized the trustees to borrow the money, using the property of the college and orphanage as security. In addition, they pledged an extra $10,000 each to Blue Mountain College and Mississippi Woman’s College. The debacle of these two special sessions taught Mississippi Baptists a lesson they had not learned from the 1892 convention (which attempted to relocate Mississippi College, only to have it overturned later): attempts to operate their institutions from the floor of the convention could lead to great confusion and chaos.

(Dr. Rogers is the author of the new book, Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State.)

A challenge to Calvinism: M.T. Martin and the controversy that rocked Mississippi Baptists in the 1890s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

In 1893, a controversy began in the Mississippi Baptist Association and eventually spread across the state. Jesse Boyd wrote, “Its rise was gradual, its force cumulative, its aftermath bitter, and its resultant breach slow in healing.”1 While it may have been a quibble over words rather than a serious breach of Baptist doctrine, it illustrates how Mississippi Baptists clashed over Calvinist doctrine by the end of the 19th century.

M. Thomas Martin was professor of mathematics at Mississippi College from 1871-80, and he also served as the business manager of The Baptist Record from 1877-81. He moved to Texas in 1883, where he had great success as an evangelist for nearly a decade, reporting some 4,000 professions of faith. However, his methods of evangelism drew critics in Texas. According to J.H. Lane, while Martin was still in Texas, “the church in Waco, Texas, of which Dr. B. H. Carroll is pastor, tried Bro. Martin some years ago, and found him way out of line, for which he was deposed from the ministry.” In 1892 Martin returned to Mississippi and became pastor of Galilee Baptist Church, Gloster (Amite). Martin preached the annual sermon at the Mississippi association in 1893. His sermon had such an effect on those present, that the clerk entered in the minutes, “Immediately after the sermon, forty persons came forward and said that they had peace with God, and full assurance for the first time.” The following year, Mississippi association reported on Martin’s mission work in reviving four churches, during which he baptized 19 people, and another 60 in his own pastorate. Soon Mississippi Baptists echoed the Texas critics that he was “way out of line,” not because he baptized so many, but because so many were “rebaptisms.”2

The crux of the controversy was Martin’s emphasis on “full assurance,” which often led people who had previously professed faith and been baptized, to question their salvation and seek baptism again. In 1895, the Mississippi association called Martin’s teachings “heresy” and censured Martin and Galilee for practicing rebaptism “to an unlimited extent, unwarranted by Scriptures.” When the association met again in 1896, resolutions were presented against Galilee for not taking action against their pastor, but other representatives said they had no authority to meddle in matters of local church autonomy. As a compromise, the association passed a resolution requesting that The Baptist Record publish articles by Martin explaining his views, alongside articles by the association opposing those views, “that our denomination may be… enabled to judge whether his teachings be orthodox or not.” The editor of The Baptist Record honored the request, and Martin’s views appeared in the paper the following year. The association enlisted R.A. Venable to write against him, but Venable declined to do so. Martin also published a pamphlet entitled The Doctrinal Views of M.T. Martin. When these two publications appeared, what had been little more than a dust devil of controversy in one association, developed into a hurricane encompassing the entire state.3

Most of Martin’s teachings on salvation were common among Baptists. Even his opponent, J.H. Lane, admitted, “Some of Bro. Martin’s doctrine is sound.” Martin taught that the Holy Spirit causes people to be aware that they are lost, and the Spirit enables people to repent and believe in Christ. He taught that people are saved by grace alone, through faith, rather than works, and when people are saved, they should be baptized as an act of Christian obedience. Martin said that salvation does not depend on one’s feelings, and that children of God have no reason to question their assurance of salvation.

These teachings were not controversial. What was controversial, however, was what Lane called “doctrine that is not Baptist,” and what T.C. Schilling said “is not in accord with Baptists.” Martin said if a man doubted his Christian experience, then he was never true a believer.

He considered such doubt to be evidence that one’s spiritual experience was not genuine, and the person needed to be baptized again. “If you have trusted the Lord Jesus Christ,” Martin would say, “you will be the first one to know it, and the last one to give it up.” He frequently said, “We do wrong to comfort those who doubt their salvation, because we seek to comfort those whom the Lord has not comforted.” Therefore, Martin called for people who questioned their salvation to receive baptism regardless of whether they had been baptized before. “I believe in real believer’s baptism, and I do not believe that one is a believer until he has discarded all self-righteousness, and has looked to Christ as his only hope forever… I believe that every case of re-baptism should stand on its own merits, and be left with the pastor and the church.”4

The 1897 session of the Mississippi association took further action against Martinism. They withdrew fellowship from Zion Hill Baptist Church (Amite) for endorsing Martin and urged Baptists not “to recognize him as a Baptist minister.” The association urged churches under the influence of Martinism to return to the “old faith of Baptists,” and if not, they would forfeit membership. When the state convention met in 1897, some wanted to leave the issue alone, but others forced it. The convention voted to appoint a committee to report “upon the subject of ‘Martinism.’” Following their report, the convention adopted a resolution of censure by a vote of 101-16, saying, “Resolved, That this Convention does not endorse, but condemns, the doctrinal views of Prof. M. T. Martin.” While a strong majority condemned Martinism, a significant minority of Baptists in the state disagreed. From 1895 to 1900, the Mississippi association declined from 31 to 22 churches, and from 3,042 to 2,208 members. In 1905, the state convention adopted a resolution expressing regret for the censure of Martin in 1897.5

Earl Kelly observed two interesting doctrinal facts that the controversy over Martinism revealed about Mississippi Baptists during this period: “First, the Augustinian conception of grace was held by the majority of Mississippi Baptists; and second, Arminianism was beginning to make serious inroads into the previously Calvinistic theology of these Baptists.” It is significant that Mississippi association referred to Martinism as a rejection of “the old faith of Baptists,” and that when J.R. Sample defended Martin, Lane pointed out that Sample was formerly a Methodist.6

(Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.)

SOURCES:

1 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists of Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 178-179.

2 Boyd, 196-197; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1893; 7; Z. T Leavell and T. J. Bailey, A Complete History of Mississippi Baptists from the Earliest Times, vol. 1 (Jackson: Mississippi Baptist Publishing Company, 1904), 68-69; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

3 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1895; 1896, 9.

4 Boyd, 179-180; The Baptist Record, March 18, 1897, May 6, 1897, June 24, 1897, 2.

5 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1897, 6, 14; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1897, 13, 17, 18, 22, 31; 1905, 47-48; Leavell and Bailey, vol. 1, 70; Boyd, 198. Martin died of a heart attack while riding a train in Louisiana in 1898, and he was buried in Gloster.

6 Earnest Earl Kelly, “A History of the Mississippi Baptist Convention from Its Conception to 1900.” (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Lousville, Kentucky, 1953), 114; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

How Mississippi Baptist views on alcohol evolved in the 19th century

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

During the 1820s and 1830s, Baptists gradually took a stronger stand against liquor. In 1820, Providence Baptist Church (Forrest County) discussed the question, “Is it lawful, according to scripture, for a member of a church to retail spiritous liquors?” The church could not agree on a position. However, in 1826, the influential Congregationalist pastor Lyman Beecher began a series of sermons against the dangers of drunkenness. He called on Christians to sign pledges to abstain from alcohol, igniting the temperance movement in America. The question came before the Mississippi association in 1827, and the association stated that it “considers drunkenness one of the most injurious and worst vices in the community.” In 1830, the Pearl River association admonished any churches hosting their meetings, “Provide no ardent spirits for the association when she may hereafter meet, as we do not want it.” In 1831, Pearl River association thanked the host church for obeying their request, and in 1832, the association humbly prayed for “the public, that they will not come up to our Association with their beer, Cider, Cakes, and Mellons, as they greatly disturb the congregation.” Likewise in 1832, the Mississippi association resolved, “that this Association do discountenance all traffic in spirituous liquors, beer, cider, or bread, within such a distance of our meetings as in any wise disturb our peace and worship; and we do, therefore, earnestly request all persons to refrain from the same.”

It had always been common to discipline members for drunkenness, but as the temperance movement grew in America, Mississippi Baptists moved gradually from a policy of tolerating mild use of alcohol, toward a policy of complete abstinence. A Committee on Temperance made an enthusiastic report in 1838 of “the steady progress of the Temperance Reformation in different parts of Mississippi and Louisiana; prejudices and opposition are fast melting away.” In 1839, D. B. Crawford gave a report to the convention on temperance which stated, “That notwithstanding, a few years since, the greater portion of our beloved and fast growing state, was under the influence of the habitual use of that liquid fire, which in its nature is so well calculated to ruin the fortunes, the lives and the souls of men, and spread devastation and ruin over the whole of our land; yet we rejoice to learn, that the cause of temperance is steadily advancing in the different parts of our State… We do therefore most earnestly and affectionately recommend to the members of our churches… to carry on and advance the great cause of temperance: 1. By abstaining entirely from the habitual use of all intoxicating liquors. 2. By using all the influence they may have, to unite others in this good work of advancing the noble enterprise contemplated by the friends of temperance.” Local churches consistently disciplined members for drunkenness, but they were slower to oppose the sale or use of alcohol. For example, in May 1844, “a query was proposed” at Providence Baptist Church (Forrest) on the issue of distributing alcohol. After discussion, the church took a vote on its opposition to “members of this church retailing or trafficking in Spirituous Liquors.” In the church minutes, the clerk wrote that the motion “unanimously carried in opposition” but then crossed out the word “unanimously.” In January 1845, Providence voted that “the voice of the church be taken to reconsider” the matter of liquor. The motion passed, but then they tabled the issue, and it did not come back up. In March of that year, a member acknowledged his “excessive use of arden[t] spirits” and his acknowledgement was accepted; he was “exonerated.”

By the 1850s, the state convention was calling not only for abstinence, but for legal action as well. In 1853, the convention adopted the report of the Temperance Committee that said, “The time has arrived when the only true policy for the advocates of Temperance to pursue, is… to secure the enactment by the Legislature of a law, utterly prohibiting the sale of ardent spirits in any quantities whatsoever.” They endorsed the enactment of the Maine Liquor Law in Mississippi. In 1851, Maine had become the first state to pass a prohibition of alcohol “except for mechanical, medicinal and manufacturing purposes,” and this law was hotly debated all over the nation, as other states considered adopting similar laws. In 1854, the Mississippi legislature banned the sale of liquors “in any quantity whatever, within five miles of said college,” referring to Mississippi College. In 1855, Ebenezer Baptist Church (Amite) granted permission to the ”sons of temperance” to build a “temperance hall” on land belonging to the church. In 1860, a member of Bethesda Baptist Church (Hinds) confessed he “had been selling ardent spirits by the gallon” and “acknowledged he had done wrong and would do so no more.” He was “requested by the church not to treat his friends with spiritous [sic] liquors when visiting his house.”

Frances E. Willard, one of the most famous temperance activists in the nation, spent a month in Mississippi in 1882 and announced, “Mississippi is the strongest of the Southern State W.C.T.U. organizations.” Every Baptist association had a temperance committee. T.J. Bailey, a Baptist minister, was the superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League. Prohibition of alcohol was such an emotionally charged issue that a liquor supporter assassinated Roderic D. Gambrell, son of Mississippi Baptist leader J.B. Gambrell and the editor of a temperance newspaper, The Sword and Shield. Nevertheless, the temperance movement was so successful that by 1897, all but five counties in Mississippi had outlawed the sale of liquor.

Book review: “Baptist Successionism: A Critical Review”

W. Morgan Patterson is a Southern Baptist historian, educated at Stetson University, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and Oxford University. This book was published in 1979, but I recently picked it up and read it in one day.

This is a concise book (four chapters, 75 pages) that analyzes the failures of the sloppy historical research of Baptists, such as Landmarkists, who believe Baptist churches are in a direct line of succession from New Testament times. The introduction explains there are four different variations of successionist writers, from those who believe they can demonstrate it and that is necessary, to those who believe neither. Chapter one explains how the successionist view was not that of the earliest Baptists, but in the 19th century it was formulated by G.H. Orchard and popularized by J.R. Graves. Chapter two shows how the successionist writers misused their sources. Chapter three shows their poor logic. Chapter four exams some of the motivations behind this erroneous view. The conclusion sums up the book, noting that the successionist view was predominant in the 19th century, but thanks to bold historians like William Whitsitt, whose research debunked the theory in the 1890s, the successionist view became a minority position among Baptist historians in the 20th century.

Patterson is scholarly historian, and he may assume a little too much about the historical knowledge of the reader when he refers to the Münster incident on page 22 without explaining that this was a violent takeover of the city of Münster, Germany in 1534 by an Anabaptist fringe group that came to be associated with Anabaptists and Baptists in the minds of their opponents, and he refers to the Whitsitt controversy on page 24 without explaining the controversy until later.

Patterson could have made his argument stronger by giving more specific details about the heretical beliefs of groups claimed by successionist writers to be Baptists, such as the Donatists, Paulicians, Cathari, etc.

While Patterson’s book is concise, it is substantive, and his reasons are sound. This is an effective critique.

The Presbyterian spy in the Baptist Church

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

The first Baptist church in Mississippi not only faced persecution from the Catholic church but was infiltrated by a Presbyterian spy.

In the 1790s the Spanish controlled the Natchez District, outlawing all public worship that was not Roman Catholic. However, in 1791, Baptist preacher Richard Curtis, Jr. organized a church on Coles Creek, 20 miles north of Natchez, later known as Salem Baptist Church. The Spanish governor, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, allowed private Protestant worship, hoping to win them over to Catholicism. However, when the priests in Natchez complained of the public worship of the Baptist congregation, Gayoso arrested Curtis in April 1795, and threatened to confiscate his property and expel him from the district if he didn’t stop. Curtis agreed, but he and his congregation decided that didn’t prohibit them from having prayer meetings and “exhortation.” Curtis even performed a wedding in May for his niece but did so secretly.

Sometime in 1795, Ebenezer Drayton was sent by Governor Gayoso to infiltrate the Baptist meetings and send back reports. He reported that at first the Baptists were “afraid of me, and they immediately guessed that I was employed by Government, which I denied.” However, he convinced them that his “feelings were much like theirs… my being of the Protestant Sect called Presbyterians and they of the Baptist.” Thus reassured, they allowed Drayton to attend their meetings, but Drayton wrote letters informing the Spanish “Catholic Majesty,” as he called him, of their activities.

Thanks to Drayton, the Spanish learned that Curtis started to go back to South Carolina, but the congregation sent four men to chase him down and insist he stay and preach to them. Considering this God’s will, Curtis returned and continued to preach. Drayton reported that Curtis agonized over his decision to stay, but told his congregation, “God says, fear not him that can kill the body only, but fear him that can cast the soul into everlasting fire… I am not ashamed not afraid to serve Jesus Christ… and if I suffer for serving him, I am willing to suffer… I would not have signed that paper if I had then known that it is the will of God that I should stay here.”

Drayton had a low opinion of Curtis and the Baptists. He wrote that the Baptists “are weak men of weak minds, and illiterate, and too ignorant to know how inconsistent they act and talk, and that they are only carried away with a frenzy or blind zeal about what they know not what…” However, Curtis seemed sharp enough to realize there was spy among them, because in July 1795, he published a letter in Natchez, explaining why he stayed, defending his religious freedom, and saying he was deeply hurt by “the malignant information against us, laid in before the authority by some who call themselves Christians.”

Thanks to their spy, the Spanish knew exactly when and where the congregation met. In August 1795, they sent a posse to arrest Curtis and two of his converts, but they fled to South Carolina, where they remained until the Spanish were forced by American authorities to leave the Natchez District.

Dr. Rogers is the author of a new history of Mississippi Baptists, to be published in 2025.

Spiritual equality of the races in antebellum Mississippi Baptist churches

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board

It may be surprising to modern readers to know that church minutes from Mississippi Baptist churches in the years before the Civil War gave every indication that while Black members were treated as unequal socially, they were treated as equal spiritually. That is, both Black and White members were received for baptism and by letter with the “right hand of Christian fellowship” and called “brother and sister,” and both Black and White members received church discipline.

In 1846, Hephzibah Church in Clarke County heard a report that a “colored sister Aggy” had “married a man who had a wife living.” They sent a committee to talk to her privately, and reported she confessed it was true but refused to change, so she was excluded from membership. However, in 1853 the same sister Aggy was repentant, forgiven, and restored to the fellowship of the church.

Bethesda Church in Hinds County had a special committee of five called, “the committee to wait on the blacks.” It was their duty to recommend any church discipline among Black members, as well as to recommend any Blacks who joined by experience of faith or church letter. This committee also invited “the widow Jones Peter to exhort the blacks when present.” In 1859, Bethesda Church charged a “Bro. J. T. Martin for striking with a stick and whipping a Negro boy of Bro. John H. Collins and against Bro. J. H. Collins prosecuting at law Bro. J.T. Martin and cultivating an unchristian spirit toward him.” A committee was sent to get the two men to reconcile, but when they refused, both men were excluded from membership. Apparently, the “committee to wait on the blacks” was made up of White members, and thus was patronizing and socially inequal; yet the very existence of the committee was a recognition of the spiritual value of all races, and their actions showed some genuine desire to protect Blacks such as the slave mentioned above.

In April of 1858, Ebenezer Church in Amite County investigated rumors that a member had killed a enslaved girl, but accepted testimony of two witnesses that her death was an accident. However, in December 1858, Ebenezer Church excluded a Peter A. Green because Green killed one of his escaped slaves when he apprehended him. This was an interesting case in which a White person was disciplined by an antebellum Mississippi Baptist church for killing a Black person. While the social inequalities allowed Green to escape murder charges, he did not escape the spiritual discipline of his church.

In no way am I implying that Blacks were treated as fully equal to Whites in Mississippi Baptist churches in the early 1800s. They were not given places of leadership and they were usually required to sit in a separate location from Whites. However, the evidence is strong that when it came to their spiritual value as brothers and sisters in Christ, Blacks were valued far more spiritually in the church than most modern readers would imagine.

SOURCES:

Minutes, Ebenezer Church, Amite County, April 17, 1858, December 18, 1858; Minutes, Bethesda Church, Hinds County, July 1849, October 1849, March 19, 1859, April 16, 1859; Minutes, Hephzibah Church, Clarke County, March 14, 1846, April 18, 1846; November 12, 1853.

Two unique Baptists from Yazoo City, Mississippi: Owen Cooper and Jerry Clower

Article copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Two of the most famous Baptists from Mississippi were laymen, not pastors. Both were members of the same church in Yazoo City, and one worked for the other.

Owen Cooper, an industrialist and deacon at First Baptist Church, Yazoo City, was a leader in Mississippi Baptist life for four decades, beginning in the 1940s. He founded Mississippi Chemical Corporation and led many humanitarian projects. Cooper eventually became the most influential layman in the Southern Baptist Convention in the twentieth century. He served as chairman of the board of trustees at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary at the time the seminary was relocated. He served on the Foreign Mission Board, where he worked closely with the area director for Southern Asia and the Pacific, Clinton native Jerry Rankin, on supporting indigenous missionaries in India. In 1959, he began serving on the Southern Baptist Executive Committee, a tenure that lasted 21 years. He was elected chairman of the SBC Executive Committee in 1971. In 1972, Cooper was elected president of the Southern Baptist Convention, serving two years. Other Mississippians had been elected president of the SBC, but they lived in other states at the time. Cooper was the first to live in Mississippi at the time he served as president of the SBC. An advocate for lay involvement in missions, Cooper was also the last layperson to be elected president of the denomination in the past 50 years. He died of cancer in 1986.

A native of Liberty, Jerry Clower was a fertilizer salesman who worked for Owen Cooper and a fellow church member of First Baptist, Yazoo City. When Clower released a record of his humorous stories, Cooper encouraged him, guaranteeing him a job if showbusiness didn’t work out. The record became a hit in 30 days, and the rest was history. In the 1970s, he began to appear regularly on “Country Crossroads,” a country and western show sponsored by the Southern Baptist Radio and TV Commission. In 1972, Clower nominated his boss and fellow church member Owen Cooper to be president of the Southern Baptist Convention with the memorable words, “Now y’all know he didn’t come to town on no watermelon truck.”2

SOURCES:

1 The Baptist Record, June 10, 1971, 1; June 22, 1972, 1; Don McGregor, The Thought Occurred to Me: A Book About Owen Cooper (Nashville: Fields Communications & Publishing, 1992), 94, 109, 127-128, 146, 149, 166-167, 169-170; “Owen Cooper (1908-1986) Business Leader and Humanitarian,” by Jo G. Prichard III, Mississippi History Now, accessed on the Internet March 7, 2023 at https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/owen-cooper-1908-1986-business-leader-and-humanitarian;

2 The Baptist Record, September 14, 1972, 1; McGregor, 169.

(Dr. Rogers is writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.)

The racial segregation in Mississippi Baptist churches after the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One the most significant social changes among Mississippi Baptists after the Civil War was the racial segregation of churches. Before the war, African people who were enslaved constituted a substantial portion of Mississippi Baptist congregations, as I have discussed in previous blog posts. In the decade after the war, Black Baptists gradually celebrated their new freedom by separating into independent, self-governing churches. In some areas this happened suddenly, and in other areas of the state it was more gradual. The First Baptist Church of Clinton, for example, had a membership of 283 in 1860, including 113 Black members. In 1866, with the absence of college students and withdrawal of Black members, the Clinton church was reduced to 36 members, and worship was only held once a month, led by a pastor from Raymond. In 1864, Jerusalem Baptist Church had 65 Black members, but all of them were gone by 1866. Bethesda Church in Hinds County agreed in 1867 to allow Black members to hold a separate revival meeting, and later in the same year the church granted the following request: “The colored members signified a desire to withdraw from the church to organize an independent church and asked permission for the use of the church house one sabbath each month.” Likewise, Black members of Academy Baptist Church in Tippah County met separately after the war, and had a Black preacher, but used the Academy church building until the 1870s. Charles Moore, a preacher who had been enslaved, expressed the common desire of Black Baptists after the war, “I didn’t expect nothing out of freedom excepting peace and happiness and the right to go my way as I please. And that is the way the Almighty wants it.”1

In other areas, Black members continued to worship alongside Whites in the same churches for a decade or more. Ebenezer Baptist Church in Amite County continued to refer to “colored” members frequently through 1874, and then there was one more mention in 1877 of a “colored” member who asked to be restored so that he could join New Hope Baptist Church. Although most churches remained integrated for several years, tensions began to arise, sometimes fueled by resentment over events of the war. For instance, in September 1865, five months after the war ended, “Eliza a colored woman” joined Sarepta Baptist Church in Franklin County by her experience of faith, and “it was moved and seconded that the right hand of fellowship be extended which was done with the exception of one brother who refused to give the right hand of fellowship to the colored woman Eliza.”2

Despite this occasional White resentment, most White Baptist leaders expressed goodwill to Black Baptists. In 1870, Salem Baptist Association in Jasper County recommended that if Black members “wish to form churches of their own, that they should be dismissed in order and assisted in doing so, but where they wish to remain with us as heretofore and are orderly, we think they should be allowed to do so.” Black membership in Salem Association declined from 206 in 1865 to 122 in 1870. As late as 1872, 81 Black people continued to worship in biracial churches in the association, and Black people continued in the records of Fellowship Baptist Church as late as 1876. The Mississippi Baptist Association reported 131 Black members in 1874.3

Segregation of Mississippi Baptist churches started out as a celebration of freedom for Black people, but by the 1890s, it had also become an expectation of Whites. The Mississippi Baptist Convention assumed that their churches were made up of White members only. For instance, the 1890 state convention referred to itself as: “The Mississippi Baptist Convention… representing a denomination of 80,000 white Christians…” However, the state convention maintained friendly relations with “colored” Baptists, a term considered polite at the time. When the General Baptist Convention of Mississippi, made up of African Americans, met at the same time as the Mississippi Baptist Convention, they frequently exchanged telegrams of Christian greetings. Mississippi Baptist pastors frequently led Bible institutes for Black Baptist pastors and deacons, and the state convention encouraged White pastors to donate their time to teach at these institutes across the state.4

SOURCES:

1 Charles E. Martin, A Heritage to Cherish: A History of First Baptist Church, Clinton, Mississippi, 1852-2002 (Nashville: Fields Publishing, Inc., 2001), 36; Randy J. Sparks, Religion in Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 139.

2 Minutes, Ebenezer Church, Amite County. November 1, 1873, May 2, 1874, October 3, 1874, July 1, 1877; Minutes, Sarepta Church, Franklin County, September 1865.

3 Sparks, 139-140; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1874.

4 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1890, 31; 1891, 14; 1897, 20-21.

Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, which was published in 2025. You can get a copy of his book by making a donation to the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission at the following link and telling them how many copies of the book you wish: https://mbcb.org/historicalcommission/ (Suggested donation $15).

The first Baptist missionary to the Mississippi Gulf Coast, John B. Hamberlin

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although Baptists were well-established in the rest of Mississippi, they were late getting started on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. In 1868, the Mississippi Baptist Convention listed the names of the Baptist ministers in Mississippi and their post offices, nearly all of which were in north or central Mississippi. Not a single Baptist minister resided on the Mississippi Coast. In 1873, W. H. Hardy of Meridian called attention to the lack of Baptist churches in Jones, Perry, Greene, Harrison and Hancock counties, and “the populous towns along the sea shore.” He called for the Convention to send missionaries to Pascagoula or Pass Christian “or some other convenient point.”

In 1875, the Mississippi Baptist Convention sent John B. Hamberlin as a missionary to the Mississippi Coast, where, he reported, there was “only one little Baptist church, and that in a disorganized state.” This church was located three miles in the country from Ocean Springs, and he relocated it in the town. He also started a church in Moss Point, which built a house of worship. Next, he targeted Biloxi, where “Roman Catholicism overshadows everything.” He found “a poor old widow” who was the only member left of a small Baptist congregation that once had a house of worship there. “He got possession of the old house, made some repairs upon it; has conducted two special meetings, and has recently organized a church of seventeen members.” Sadly, a yellow fever epidemic in 1876 took the life of Hamberlin’s wife while they were in Biloxi, and he sent his small child inland to get away from the epidemic, while he returned to his mission work on the Coast. Hamberlin wrote, “My wife is dead; my home is broken up; my child is gone, and my heart is desolate; but I hope in the future to be a better man, and to do more and better work for Christ than ever before.”

SOURCE:

Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1868, 22-23, 29-30; 1873, 17-18; 1875, 12; 1876, 24-25.

Rev. T. C. Teasdale’s daring adventure with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most amazing but lesser-known stories of the Civil War is how a Mississippi Baptist preacher got both Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln to agree to help him sell cotton across enemy lines in order to fund an orphanage. Although the plan collapsed in the end, the story is still fascinating.

Since over 5,000 children of Mississippi Confederate soldiers were left fatherless, an interdenominational movement started in 1864 to establish a home for them. On October 26, 1864, the Mississippi Baptist Convention accepted responsibility for the project. The Orphans’ Home of Mississippi opened in October 1866 at Lauderdale, after considerable effort, especially by one prominent pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale.1

Rev. Teasdale was in a unique position to aid the Orphans’ Home, because of his influential contacts in both the North and South. A New Jersey native, he came to First Baptist Church, Columbus, Mississippi in the 1850s from a church in Washington, D.C. When the Civil War erupted, he left his church to preach to Confederate troops in the field. In early 1865, he returned from preaching among Confederate soldiers to assist with the establishment of the Orphans’ Home of Mississippi. He launched a creative and bold plan to raise money and solve a problem of donations. A large donation of cotton was offered to the orphanage, and the cotton could bring 16 times more money in New York than in Mississippi, but how could they sell it in New York with the war still raging? Since Teasdale had been a pastor in Springfield, Illinois and Washington, D.C. and had preached to the Confederate armies, he was personally acquainted with both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln (from Illinois) and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and many of their advisers. In February and March 1865, he set out on a dangerous journey by horseback, boat, railroads, stagecoach and foot, dodging Sherman’s march through Georgia, crossing through the lines of the armies of both sides, and conferred in Richmond and Washington, seeking permission from both sides to sell the cotton in New York for the benefit of the orphanage.2

Confederate President Davis readily agreed, and on March 3, 1865, Davis signed the paper granting permission for the sale. Next, Dr. Teasdale slipped across enemy lines and entered Washington, a city he knew well, since he was a former pastor in the city. He waited in line for several days for an audience with President Lincoln, but he could not get in, since government officials in line were always a higher priority than a private citizen. Finally, he sent a note to Mr. Lincoln, whom he knew when they both lived in Springfield, Illinois, saying that he was now a resident of Mississippi and that he was there on a mission of mercy. Lincoln received him, and he listened to the plea for cotton sales to support the orphanage, but the president was skeptical. Why should he help Mississippi, a State in rebellion against the United States? In his autobiography, Teasdale records Lincoln’s words: “We want to bring you rebels into such straits, that you will be willing to give up this wicked rebellion.” Dr. Teasdale replied, “Mr. President, if it were the big people alone that were concerned in this matter, I should not be here, sir. They might fight it out to the bitter end, without my pleading for their relief. But sir, when it is the hapless little ones that are involved in this suffering, who, of course, who had nothing to do with bringing about the present unhappy conflict between the sections, I think it is a very different case, and one deserving of sympathy and commiseration.” Lincoln instantly said, “That is true; and I must do something for you.” With that, Lincoln signed the paper, granting permission for the sale. It was March 18, 1865. However, a few weeks later, on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army to Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant. By the time Teasdale returned home, the war was over, the permission granted by Jefferson Davis no longer had authority, Lincoln was assassinated, and Teasdale abandoned his plans. Teasdale said, “This splendid arrangement failed, only because it was undertaken a little too late.” Undaunted, Dr. Teasdale volunteered as a fundraising agent for the orphanage and staked his large private fortune on its success. Rarely has there been a more daring donor to a Christian cause!3

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 12-17; 1867, 29-31.

2 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists in Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 131.

3 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 173-174, 187-203; Boyd, 130-132; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 14-16.

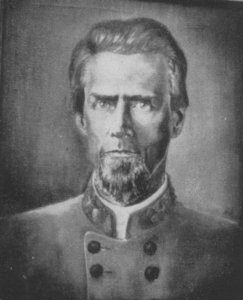

M.P. Lowrey, Mississippi’s “fighting preacher” in the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most interesting Mississippi veterans of the Civil War was M. P. (Mark Perrin) Lowrey. Lowrey was a veteran of the Mexican War, then a brick mason who became a Baptist preacher in 1852. When the Civil War began, he was pastor of the Baptist churches at Ripley in Tippah County and Kossuth in Alcorn County. Like many of his neighbors in northeast Mississippi, he did not believe in slavery, yet he went to Corinth and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He was elected colonel and commanded the 32nd Mississippi Regiment. Lowrey commanded a brigade at the Battle of Perryville, where he was wounded. Most of his military career was in Hood’s campaign in Tennessee and fighting against Sherman in Georgia. He was promoted to brigadier-general after his bravery at Chickamauga, and played a key role in the Confederate victory at Missionary Ridge. In addition to fighting, he preached to his troops. One of his soldiers said he would “pray with them in his tent, preach to them in the camp and lead them in the thickest of the fight in the battle.” Another soldier said Lowrey “would preach like hell on Sunday and fight like the devil all week!” He was frequently referred to as the “fighting preacher of the Army of Tennessee.” He led in a revival among soldiers in Dalton, Georgia, and afterwards baptized 50 of his soldiers in a creek near the camp. After the war, Lowrey founded Blue Mountain College in Tippah County, and the Mississippi Baptist Convention elected Lowrey president for ten years in a row, 1868-1877.

SOURCES:

John T. Christian, “A History of the Baptists of Mississippi,” Unpublished manuscript, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission Archives, Clinton, Mississippi, 1924, 135, 197; Robbie Neal Sumrall, A Light on a Hill: A History of Blue Mountain College (Nashville: Benson Publishing Company, 1947), 6-12.

Dr. Rogers is currently revising and updating A History of Mississippi Baptists.

FBC Columbus, MS: One of the finest antebellum Baptist church buildings in the South

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Columbus, Mississippi had one of the finest antebellum Baptist church buildings in the South.

First Baptist Church, Columbus, MIssissippi, in Lowndes County, built a magnificent brick house of worship before the Civil War. Construction began in 1838 and was completed in 1840. The building was demolished about 1905 for a new sanctuary, so descriptions are based upon existing photographs. Richard J. Cawthon, author of Lost Churches of Mississippi, says “it must have been the most elegant house of worship in Mississippi and one of the largest and finest Baptist meeting houses in the South.” The annual meeting of the Mississippi Baptist Convention was held in this building on November 10-13, 1853, and the Southern Baptist Convention was scheduled to meet in this building in 1863, but the meeting was cancelled due to the Civil War. It was located at the northeast corner of Seventh Street North (originally Caledonia Street) and First Avenue North (originally Military Street). Facing westward, it was a rectangular temple-form building, had a tetrastyle portico with four fluted columns in front. Above the triangular arch near the front, was an eye-catching, unusual steeple that appeared to copy the five-tier octagonal spire that Sir Christopher Wren placed on St. Bride’s Church in London in the late seventeenth century. The steeple had a square base, which ascended with five tiers of eight-sided drums, each tier proportionately smaller as it rose higher. The windows indicated that it had a split-level interior with stairs to an elevated auditorium and stairs down to another level below, perhaps for classrooms. Its similarity to the Lyceum at the University of Mississippi, designed by architect William Nichols, indicate that the Columbus Church could have also been designed by Nichols, who was also the designer of the Old State Capitol in Jackson.

SOURCES:

Richard J. Cawthon, Lost Churches of Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), 41-46; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1853 Annual, Southern Baptist Convention, 1861, 13.

Dr. Rogers is currently revising and updating A History of Mississippi Baptists.

How Baptists acquired Mississippi College

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Mississippi College had been founded at Clinton in 1826 as Hampstead Academy, by a group of local citizens interested in education for their children. Thirty students enrolled for the first time in 1827. Its founders were influential people; they included H. G. Runnels, who was to become governor of the State. In 1827 the legislature changed its name to Mississippi Academy, and then in 1830 the name was changed to Mississippi College, with the authority to grant “such degrees in the arts, sciences and languages, as are usually conferred in the most respectable colleges in the United States.”1

Mississippi College was divided into a female and male department, each with its own faculty. The female department prospered better than the male department, and in 1831, the college became the first coeducational institution in America to grant degrees to women: Alice Robinson and Catherine Hall. The curriculum for women in 1837 included Latin, Greek, French, music and fine art. Supporters of Mississippi College hoped it would be adopted by the legislature as the State University, especially since the legislature allowed it to be financed by public land monies. However, in 1840 the legislature established the University of Mississippi, and began to select a location (eventually choosing Oxford), which ruled out a possibility of Mississippi College becoming the state’s university. At this point, the trustees looked for a religious denomination to sponsor the school. They offered the college to the Methodists, who accepted but then quickly rescinded their decision in 1841, since they had created their own school, Centenary College, not far away in Brandon Springs. The trustees then turned to the Presbyterians, who accepted, and in 1842 the Clinton Presbytery of the Mississippi Synod assumed control of the college. The Presbyterians operated the institution from 1842 to 1850 with considerable success. However, the Presbyterian denomination was suffering theological and political schisms between “Old” and “New” schools, dividing between North and South, much as Baptists had divided. These struggles, along with competition for funds with another Presbyterian school, Oakland College, forced the trustees to offer Mississippi College to the State in 1848 a “normal” college to educate teachers. The legislature refused, so in 1850 the Clinton Presbytery severed ties to the college, and the trustees surrendered the school to the citizens of Clinton.2

Clinton was not able to manage the college by itself. Although Hinds County in 1850 was a prosperous, growing county, with a population of over 25,000, and a railroad line had been completed from Vicksburg, through Clinton to Jackson, Clinton itself was still only a village of a few hundred people. The citizens of Clinton could not support the college by themselves, and the enrollment of the school was not yet large enough to support the college on its own. Even the faculty selected for the 1850-51 session, which included a Baptist as president, William Carey Crane, were unable or unwilling to accept the responsibility. At this point, a Methodist pastor suggested giving Mississippi College to the Baptists, and a wealthy Baptist leader seized on the opportunity. Rev. Thomas Ford, minister of the Methodist Church in Clinton, suggested that the Mississippi Baptist Convention sponsor the college. Benjamin Whitfield, a wealthy planter and pastor in Hinds County, and one of the founders of the Mississippi Baptist Convention, was elected a trustee of the college on August 12. If the transfer was to be made to the Baptists, quick action was needed, because there was a rival proposal for the Baptists “of building up a college at Raymond,” which was going to be presented to the State Convention in November. A committee that included Whitfield negotiated the deal on November 1, and when the Mississippi Baptist Convention met in Jackson on November 7, the committee recommended that the project at Raymond be rejected as “impracticable, because of the expense it would involve the Convention.” Then the committee said, “The Trustees of the ‘Mississippi College,’ located at Clinton, Hinds county, offer control of the College, unincumbered by a cent of debt… The property is understood to be worth eleven thousand dollars. It is recommended, that the tender be at once accepted.” The resolution passed, and the dream of Mississippi Baptists for a college of their own was realized.3

SOURCES:

1 Board of Trustees of Mississippi College, Minute Book I, 3, 5, 7. Also see Isaac Caldwell to John A. Quitman, April 11, 1828, in Jesse L. Boyd, Good Reasons for a History of Mississippi College, 6-7. These materials are in the archives, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission, Leland Speed Library, Mississippi College, Clinton, Mississippi.

2 Aubrey Keith Lucas, “Education in Mississippi from Statehood to the Civil War,” in A History of Mississippi, vol. 1, Richard Aubrey McLemore, ed. (Hattiesburg: University and College Press of Mississippi, 1973), 360-361; “Mississippi College Timeline,” accessed on the Internet 30 April 2022 at http://www.mc.edu/about/history/timeline; W. H. Weathersby, “A History of Mississippi College,” Publications of Mississippi Historical Society, Centenary Series, V, 184-219. Also see Minute Book I, 51, 56.

3 U.S. Census, “Population of the United States in 1850: Mississippi,” accessed on the Internet 30 April 2022 at https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850a-34.pdf. The population of Clinton is not even listed in 1850. In 1860, Clinton is listed as having 289 citizens. U.S. Census, “Population of the United States in 1860: Mississippi,” accessed on the Internet 30 April 2022 at https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-22.pdf; Board of Trustees of Mississippi College, Minute Book I, 88-90; Clinton News, Dec. 1967; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1850, 27.

Dr. Rogers is currently revising and updating A History of Mississippi Baptists.

How Mississippi Baptists came to oppose alcohol in the early 1800s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Baptists have not always been as adamantly opposed to alcohol as they are today; rather, their view developed over several decades in the early 1800s. This can be illustrated in the story of how Mississippi Baptists gradually took a stronger stand against liquor during the decades from the 1820s through the 1850s. In 1820, Providence Baptist Church in what is now Forrest County discussed the question, “Is it lawful, according to scripture, for a member of a church to retail spiritous liquors?” The church could not agree on a position in regard to the matter. This attitude would begin to change in the 1820s, however. In 1826, the influential Congregationalist pastor Lyman Beecher began a series of sermons against the dangers of drunkenness and urged the necessity of abstinence from the alcohol. He called on Christians to sign pledges to abstain from alcohol, igniting the temperance movement in America. The question came before the Mississippi Baptist Association in 1827, and it was stated that it “considers drunkenness one of the most injurious and worst vices in the community.” In 1830, the Pearl River Baptist Association admonished any churches hosting their meetings, “provide no ardent spirits for the association when she may hereafter meet, as we do not want it.” In 1831, Pearl River Association thanked the host church for obeying their request, and in 1832, the association humbly prayed “the public, that they will not come up to our Association with their beer, Cider, Cakes, and Mellons, as they greatly disturb the congregation.” Likewise in 1832, Mississippi Association resolved, “That this Association do discountenance all traffic in spirituous liquors, beer, cider, or bread, within such a distance of our meetings as in any wise disturb our peace and worship; and we do, therefore, earnestly request all persons to refrain from the same.”1

It had always been common for Baptists to discipline members for drunkenness, but as the temperance movement grew in America, Mississippi Baptists moved gradually from a policy of tolerating mild use of alcohol, toward a policy of complete abstinence from alcohol. A Committee on Temperance made an enthusiastic report in 1838 of “the steady progress of the Temperance Reformation in different parts of Mississippi and Louisiana; prejudices and opposition are fasting melting away.” In 1839, D. B. Crawford gave a report to the Mississippi Baptist Convention on temperance which stated, “That notwithstanding, a few years since, the greater portion of our beloved and fast growing state, was under the influence of the habitual use of that liquid fire, which in its nature is so well calculated to ruin the fortunes, the lives and the souls of men, and spread devastation and ruin over the whole of our land; yet we rejoice to learn, that the cause of temperance is steadily advancing in the different parts of our State… We do therefore most earnestly and affectionately recommend to the members of our churches… to carry on and advance the great cause of temperance: 1. By abstaining entirely from the habitual use of all intoxicating liquors. 2. By using all the influence they may have, to unite others in this good work of advancing the noble enterprise contemplated by the friends of temperance.” Local churches consistently disciplined members for drunkenness, but they were slower to oppose the sale or use of alcohol. For example, in May 1844, “a query was proposed” at Providence Baptist Church in Forrest County on the issue of distributing alcohol. After discussion, the church took a vote on its opposition to “members of this church retailing or trafficking in Spirituous Liquors.” It is significant that in the handwritten church minutes, the clerk wrote that the motion “unanimously carried in opposition,” but then crossed out the word “unanimously.” In January 1845, Providence Church voted that “the voice of the church be taken to reconsider” the matter of liquor. The motion passed, but then tabled the issue, and did not come back up. In March of that year, a member acknowledged his “excessive use of arden[t] spirits” and his acknowledgement was accepted, and he was “exonerated.”2

. In 1846, the Mississippi Baptist Association’s leadership was opposed to alcohol, but was still attempting to prohibit the use of alcohol at its own meetings. The Association passed a resolution saying, “We respectfully request the brethren and friends who may entertain this body at its future meetings, to refrain from presenting ardent spirits in their accommodations.” By the 1850s, the State Convention was calling not only for abstinence, but for legal action, as well. In 1853, the Convention adopted the report of the “Temperance” Committee that said, “The time has arrived when the only true policy for the advocates of Temperance to pursue, is… to secure the enactment by the Legislature of a law, utterly prohibiting the sale of ardent spirits in any quantities whatsoever.” They endorsed the enactment of the “The Maine Liquor Law” in Mississippi. Two years before, in 1851, Maine had become the first State to pass a prohibition of alcohol. Thus during the antebellum period Mississippi Baptists gradually came to favor abstinence and prohibition of alcohol.3

SOURCES:

1 Aaron Menikoff, Politics and Piety: Baptist Social Reform in America, 1770-1860 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2014), 162-163; T.C. Schilling, Abstract History of the Mississippi Baptist Association for One Hundred Years From its Preliminary Organization in 1806 to the Centennial Session in 1906 (New Orleans, 1908), 50; Minutes, Pearl River Baptist Association, 1830, 1831, 1832.

2 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1838, 1839; Minutes, Providence Baptist Church, Forrest County, Mississippi, May 11, 1844, January 11, 1845, March 8, 1845.

3 T. M. Bond, A Republication of the Minutes of the Mississippi Baptist Association (New Orleans: Hinton & Co., 1849), 250; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1853, 26; “The Unintended Consequences of Prohibition: Introduction,” Washington State University, accessed online 17 April 2022 at http://digitalexhibits.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/prohibition-in-the-u-s/introduction.