Blog Archives

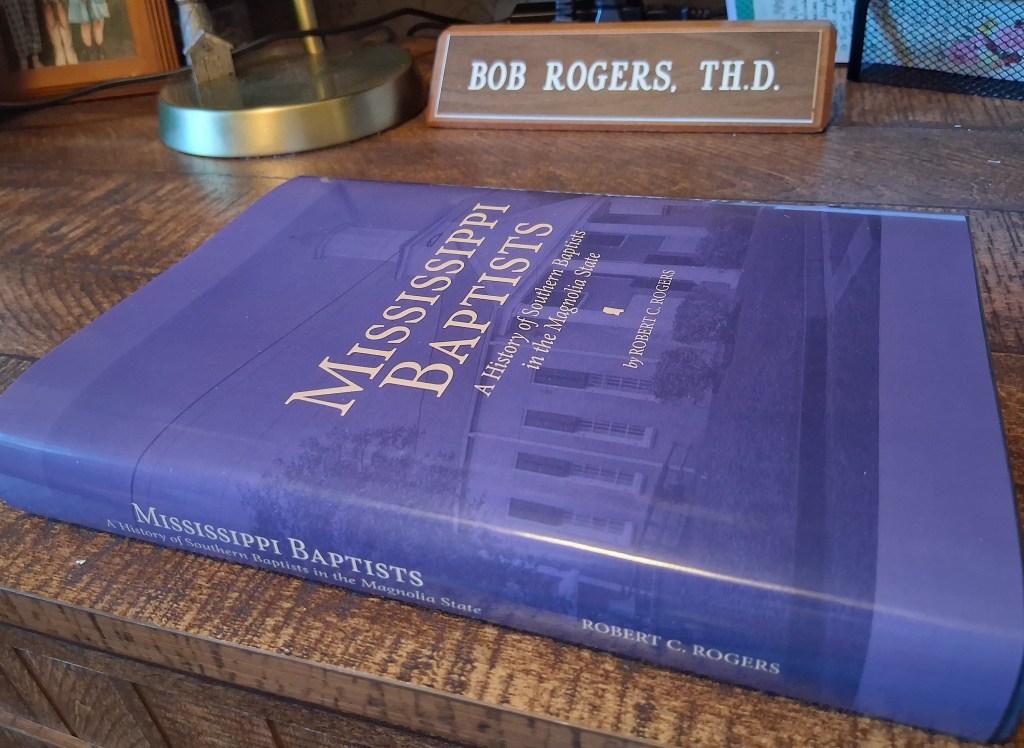

My new Miss. Baptist history book is now available!

My new book, Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, has been published by the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, and is now available to the public. It is a hardback book, 300 pages of text, plus four appendices, notes, and an index in the back.

In 2021, I signed a contract with the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board and Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission to revise and update R.A. McLemore’s book published in 1971, A History of Mississippi Baptists. While the new work is based on McLemore’s history, it has many more new features than simply the addition of a half century of recent history. I have included new research from the beginning. For example, I discovered evidence that the mother church of Mississippi Baptists was Ebenezer Baptist Church, Florence, South Carolina. Other new research includes the declaration of religious liberty by Richard Curtis, Jr., the first Baptist pastor in Mississippi; social and cultural information on typical Baptist life during different time periods; trends in Baptist theology; and details of the previously untold story of the McCall controversy of 1948-49. Throughout the book, I sought to write in a narrative style, including anecdotes that reflected the flavor of Baptist life.

You can get a book by making a donation to the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission at the link below. Click on “Donate to the Historical Commission,” then fill out the form, select “MS Baptist Historical Commission” and how much you will donate (I suggest at least $15 to cover their costs), and how many copies of the book you want.

Here is the link: https://mbcb.org/historicalcommission/

The chaotic 1930 special session of the Miss. Baptist Convention

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

On July 15, 1930, an unprecedented second special session of the Mississippi Baptist Convention met in Newton, attended by 318 messengers. It turned into chaos.

(A first special session had been held in April to respond to the problems of the Great Depression by closing Clarke College and moving the Mississippi Baptist Orphanage to the campus of Clarke; however, some legal matters were not handled, so a second special session was called.)

This second special session erupted into a chaotic state of confusion, described by The Baptist Record as featuring “unanimous disagreement, often vociferously expressed.” MBCB executive R.B. Gunter made a plea for harmony, but it went unheard. W.N. Taylor of Clinton presented resolutions to continue Clarke College and keep the orphanage near Jackson, in effect to rescind the vote of the previous session. Convention president Gates ruled the resolutions out of order, but a challenge was made to his ruling; the messengers voted 164-154 to sustain his ruling. Next, M.P. Love of Hattiesburg moved that the property of the orphanage be mortgaged to pay the debts of Clarke College, but his resolutions were voted down. At a stalemate, the messengers then adjourned to dinner.

The Baptist Record commented that the only thing the messengers agreed about was that “the people of Newton and vicinity furnished a good dinner.” After dinner, the messengers returned and reversed their earlier actions. This time, Gates’ ruling was overturned. Next, the messengers adopted Taylor’s resolutions, voting to keep the orphanage in Jackson and to re-open Clarke College. To pay for it, the messengers authorized the trustees to borrow the money, using the property of the college and orphanage as security. In addition, they pledged an extra $10,000 each to Blue Mountain College and Mississippi Woman’s College. The debacle of these two special sessions taught Mississippi Baptists a lesson they had not learned from the 1892 convention (which attempted to relocate Mississippi College, only to have it overturned later): attempts to operate their institutions from the floor of the convention could lead to great confusion and chaos.

(Dr. Rogers is the author of the new book, Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State.)

Mississippi Baptists and the civil rights struggle in the 1950s and 1960s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court struck down public school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, saying, “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The Southern Baptist Convention, meeting only weeks later, became the first major religious denomination to endorse the decision, saying, “This Supreme Court decision is in harmony with the constitutional guarantee of equal freedom to all citizens, and with the Christian principles of equal justice and love for all men.” Mississippi Baptists, however, would have none of it. A.L. Goodrich, editor of The Baptist Record, accused the Southern Baptist Convention of inconsistency on the issue for not endorsing other types of integration as well. Goodrich was “indignant” at this example of “the church putting its finger in state matters,” but he told Mississippi Baptist readers that they “need not fear any results from this action.” First Baptist Church, Grenada (Grenada) made a statement condemning the Supreme Court decision. The Mississippi Baptist Convention, meeting November 16-18, 1954, passed several resolutions, but it made no mention of the Supreme Court decision.1

The Supreme Court deferred application of integration, and Mississippi’s governor, Hugh White, met with Black leaders, expecting that they would agree to maintain segregated schools if the state improved funding for Black schools. H.H. Humes represented the largest Black denomination in the state, as president of the 400,000-member General Missionary Baptist Convention. He responded to the governor, “the real trouble is that for too long you have given us schools in which we could study the earth through the floor and the stars through the roof.”2

In the 1950s, most White Baptists were content with a paternalistic approach of sponsoring ministry to Black Baptists, while keeping their schools, churches and social interaction segregated. There were some rare exceptions. Ken West recalls attending Gunnison Baptist Church, (Bolivar) in the 1950s, when the congregation had several Black members of the church, mostly women, who actively participated in WMU. However, most White Baptists agreed with W. Douglas Hudgins, pastor of First Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds), who told reporters that he did not expect “Negroes” to try to join his church. When pressed specifically about the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court, Douglas evasively called it “a political question and not a religious question.” Alex McKeigney, a deacon from First Baptist Church, Jackson, was more direct, saying that “the facts of history make it plain that the development of civilization and of Christianity itself has rested in the hands of the white race” and that support of school desegregation “is a direct contribution to the efforts of those groups advocating intermarriage between the races.” Dr. D.M. Nelson, president of Mississippi College, wrote a tract in support of segregation that was published by the White Citizens’ Council in 1954. In the tract, Nelson said that in part, the purpose of integration was “to mongrelize the two dominant races of the South.” Baptist lay leader Owen Cooper recalled that during the 1950s, he avoided the moral issue that troubled him later: “To be quite honest I did not ask myself what Jesus Christ would have done had He been on earth at the time. I didn’t ask because I already knew the answer.”3

In 1960, Baptist home missionary Victor M. Kaneubbe sparked controversy over segregated schools for another racial group in Mississippi, the American Indians. Kaneubbe was a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, who came to Mississippi to do mission work with the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. However, since his wife was White, no public schools would admit their daughter, Vicki. The White schools denied Vicki because she was Choctaw, and the Choctaw schools denied her because she was White. Kaneubbe enlisted the support of many White Baptists who campaigned for Vicki. This eventually led to the establishment Choctaw Central High School on the Pearl River Reservation in Neshoba County, an integrated school that admitted students with partial Choctaw blood.4

The minutes of Woodville Heights Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds) illustrate how local churches began to struggle with the issue of integration in the 1960s. At the monthly business meeting of Woodville Heights in August 1961, the issue of racial integration came up. The minutes read, “Bro. Magee gave a short talk on integration attempts. Bro. Sullivan gave his opinion on this subject. Bro. Sullivan said he would contact Sheriff Gilfoy concerning the furnishing of a Deputy during our services.” Interestingly, the very next month, the pastor, Dr. Percy F. Herring, resigned, and so did one of the trustees, Samuel Norris. In his resignation letter, Herring did not make a direct reference to the integration issue, only saying, “My personal circumstances and the situation here in the community have combined to bring me to the conclusion that I should submit my resignation as Pastor of this church.”5

Woodville Heights was not alone in the struggle. Throughout the 1960s, many Mississippi Baptists wrestled with racism in their local churches, associations, and the state convention. In the early part of the decade, it was common for Southern Baptist churches in Mississippi to have what was called a “closed door policy” against attendance by Black people. White Baptists were known to be active in the Ku Klux Klan, such as Sam Bowers, leader of the White Knights of the KKK, who taught a men’s Sunday school class at a Baptist church in Jones County. Some Baptist leaders were disturbed by the violence of the KKK. In November 1964, a few months after the murders of civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Owen Cooper presented a resolution on racism at the state convention. Cooper’s resolution, which was adopted, recognized that “serious racial problems now beset our state,” and said, “we deplore every action of violence… We would urge all Baptists in the state to refrain from participating in or approval of any such acts of lawlessness.” In 1965, it was front-page news in The Baptist Record when First Baptist Church, Richmond, Virginia admitted two Nigerian college students as members. When First Baptist Church, Montgomery, Alabama adopted an “open door policy” toward all races the same year, it was again news in The Baptist Record. Clearly, it was not yet the norm in White Mississippi Baptist churches.6

As the decade progressed, some Mississippi Baptists began to accept integration and work toward racial justice and reconciliation. Tom Landrum, a Baptist layman in Jones County, secretly spied on the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Landrum’s reports to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) were instrumental in the arrest of the Klansmen who killed civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer in 1965. Earl Kelly, in his presidential address in 1966, told the Mississippi Baptist Convention that “the race question” had to be faced. Baptist deacon Owen Cooper took this challenge seriously, helping to charter and becoming chairman of Mississippi Action for Progress (MAP) on September 13, 1966; MAP was able to secure millions of dollars to keep alive Head Start programs, which primarily benefitted impoverished Black children, that were in danger of losing their funds. When civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, The Baptist Record quoted Baptist leaders who expressed “shock, grief and dismay at the murder” of King. In 1969, Jerry Clower, the popular Mississippi entertainer and member of First Baptist Church, Yazoo City (Yazoo), was speaking out against racism at Baptist events. Clower confessed that as a child, he was taught that “a Negro did not have a soul, but he found out he was wrong when he became a Christian.” By that year, 1969, all the state colleges and hospitals had agreed to sign an assurance of compliance with racial integration.7

(Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.)

SOURCES:

1 Jesse C. Fletcher, The Southern Baptist Convention: A Sesquicentennial History (Nashville: Broadman and Holman Publishers, 1994), 200; Annual, Southern Baptist Convention, 1954, 36; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1954, 45-49; The Baptist Record, June 10, 1954, 1, 3; July 8, 1954, 4.

3 Ibid, 62-63; Letter from Ken West, Leland, Mississippi, to Bob Rogers, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 28 January 2022, Original in the hand of Robert C. Rogers; D. M. Nelson, Conflicting Views on Segregation (Greenwood, MS: Educational Fund of the Citizens’ Council, 1954), 5, 10; The Clarion-Ledger, April 4, 1982, cited in Dittmer, 63.

4 Jamie Henton, “Their Culture Against Them: The Assimilation of Native American Children Through Progressive Education, 1930-1960s,” Master’s Theses, University of Southern Mississippi, 2019, 85-92.

5 Minutes, Woodville Heights Baptist Church, Jackson, Mississippi, August 9, 1961; September 6, 1961.

6 Curtis Wilkie, When Evil Lived in Laurel: The ‘White Knights’ and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer (New York: W.W. North & Company, 2021), 26, 43-51; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1964, 43-44; The Baptist Record, January 28, 1965, 1; April 29, 1965, 2.

7 Wilkie, 20, 138; Dittmer, 377-378; The Baptist Record, November 17, 1966, 1, 3; December 21, 1967; April 11, 1968, 1; July 17, 1969, 1, 2; November 29, 1969, 1.

A challenge to Calvinism: M.T. Martin and the controversy that rocked Mississippi Baptists in the 1890s

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

In 1893, a controversy began in the Mississippi Baptist Association and eventually spread across the state. Jesse Boyd wrote, “Its rise was gradual, its force cumulative, its aftermath bitter, and its resultant breach slow in healing.”1 While it may have been a quibble over words rather than a serious breach of Baptist doctrine, it illustrates how Mississippi Baptists clashed over Calvinist doctrine by the end of the 19th century.

M. Thomas Martin was professor of mathematics at Mississippi College from 1871-80, and he also served as the business manager of The Baptist Record from 1877-81. He moved to Texas in 1883, where he had great success as an evangelist for nearly a decade, reporting some 4,000 professions of faith. However, his methods of evangelism drew critics in Texas. According to J.H. Lane, while Martin was still in Texas, “the church in Waco, Texas, of which Dr. B. H. Carroll is pastor, tried Bro. Martin some years ago, and found him way out of line, for which he was deposed from the ministry.” In 1892 Martin returned to Mississippi and became pastor of Galilee Baptist Church, Gloster (Amite). Martin preached the annual sermon at the Mississippi association in 1893. His sermon had such an effect on those present, that the clerk entered in the minutes, “Immediately after the sermon, forty persons came forward and said that they had peace with God, and full assurance for the first time.” The following year, Mississippi association reported on Martin’s mission work in reviving four churches, during which he baptized 19 people, and another 60 in his own pastorate. Soon Mississippi Baptists echoed the Texas critics that he was “way out of line,” not because he baptized so many, but because so many were “rebaptisms.”2

The crux of the controversy was Martin’s emphasis on “full assurance,” which often led people who had previously professed faith and been baptized, to question their salvation and seek baptism again. In 1895, the Mississippi association called Martin’s teachings “heresy” and censured Martin and Galilee for practicing rebaptism “to an unlimited extent, unwarranted by Scriptures.” When the association met again in 1896, resolutions were presented against Galilee for not taking action against their pastor, but other representatives said they had no authority to meddle in matters of local church autonomy. As a compromise, the association passed a resolution requesting that The Baptist Record publish articles by Martin explaining his views, alongside articles by the association opposing those views, “that our denomination may be… enabled to judge whether his teachings be orthodox or not.” The editor of The Baptist Record honored the request, and Martin’s views appeared in the paper the following year. The association enlisted R.A. Venable to write against him, but Venable declined to do so. Martin also published a pamphlet entitled The Doctrinal Views of M.T. Martin. When these two publications appeared, what had been little more than a dust devil of controversy in one association, developed into a hurricane encompassing the entire state.3

Most of Martin’s teachings on salvation were common among Baptists. Even his opponent, J.H. Lane, admitted, “Some of Bro. Martin’s doctrine is sound.” Martin taught that the Holy Spirit causes people to be aware that they are lost, and the Spirit enables people to repent and believe in Christ. He taught that people are saved by grace alone, through faith, rather than works, and when people are saved, they should be baptized as an act of Christian obedience. Martin said that salvation does not depend on one’s feelings, and that children of God have no reason to question their assurance of salvation.

These teachings were not controversial. What was controversial, however, was what Lane called “doctrine that is not Baptist,” and what T.C. Schilling said “is not in accord with Baptists.” Martin said if a man doubted his Christian experience, then he was never true a believer.

He considered such doubt to be evidence that one’s spiritual experience was not genuine, and the person needed to be baptized again. “If you have trusted the Lord Jesus Christ,” Martin would say, “you will be the first one to know it, and the last one to give it up.” He frequently said, “We do wrong to comfort those who doubt their salvation, because we seek to comfort those whom the Lord has not comforted.” Therefore, Martin called for people who questioned their salvation to receive baptism regardless of whether they had been baptized before. “I believe in real believer’s baptism, and I do not believe that one is a believer until he has discarded all self-righteousness, and has looked to Christ as his only hope forever… I believe that every case of re-baptism should stand on its own merits, and be left with the pastor and the church.”4

The 1897 session of the Mississippi association took further action against Martinism. They withdrew fellowship from Zion Hill Baptist Church (Amite) for endorsing Martin and urged Baptists not “to recognize him as a Baptist minister.” The association urged churches under the influence of Martinism to return to the “old faith of Baptists,” and if not, they would forfeit membership. When the state convention met in 1897, some wanted to leave the issue alone, but others forced it. The convention voted to appoint a committee to report “upon the subject of ‘Martinism.’” Following their report, the convention adopted a resolution of censure by a vote of 101-16, saying, “Resolved, That this Convention does not endorse, but condemns, the doctrinal views of Prof. M. T. Martin.” While a strong majority condemned Martinism, a significant minority of Baptists in the state disagreed. From 1895 to 1900, the Mississippi association declined from 31 to 22 churches, and from 3,042 to 2,208 members. In 1905, the state convention adopted a resolution expressing regret for the censure of Martin in 1897.5

Earl Kelly observed two interesting doctrinal facts that the controversy over Martinism revealed about Mississippi Baptists during this period: “First, the Augustinian conception of grace was held by the majority of Mississippi Baptists; and second, Arminianism was beginning to make serious inroads into the previously Calvinistic theology of these Baptists.” It is significant that Mississippi association referred to Martinism as a rejection of “the old faith of Baptists,” and that when J.R. Sample defended Martin, Lane pointed out that Sample was formerly a Methodist.6

(Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.)

SOURCES:

1 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists of Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 178-179.

2 Boyd, 196-197; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1893; 7; Z. T Leavell and T. J. Bailey, A Complete History of Mississippi Baptists from the Earliest Times, vol. 1 (Jackson: Mississippi Baptist Publishing Company, 1904), 68-69; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

3 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1895; 1896, 9.

4 Boyd, 179-180; The Baptist Record, March 18, 1897, May 6, 1897, June 24, 1897, 2.

5 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Association, 1897, 6, 14; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1897, 13, 17, 18, 22, 31; 1905, 47-48; Leavell and Bailey, vol. 1, 70; Boyd, 198. Martin died of a heart attack while riding a train in Louisiana in 1898, and he was buried in Gloster.

6 Earnest Earl Kelly, “A History of the Mississippi Baptist Convention from Its Conception to 1900.” (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Lousville, Kentucky, 1953), 114; The Baptist Record, May 6, 1897.

Natchez to New Orleans: How those “country Baptists” of Mississippi sought to reach the cities in the antebellum era

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although Mississippi had grown to a population of nearly 800,000 by the Civil War, the vast majority lived in rural areas. Like the citizens, Mississippi Baptist churches were more often in rural settlements than towns, and few were on the Gulf Coast. Pearl River Baptist Association only had one church in a coastal county, Red Creek Baptist Church (Harrison), and Red Creek was a rural area inland from the coast. By 1860, though, several towns in Mississippi had over 1,000 residents: Natchez was the largest, with 6,619 residents, followed by Vicksburg with 4,591, Columbus with 3,308, Jackson with 3,199, Holly Springs with 2,987, and Port Gibson with 1,453. Clinton, home of Mississippi College, had 289 citizens.1

Although the Columbus Baptist Church, Columbus (Lowndes) was thriving, the Mississippi Baptist Convention recognized the need to plant churches in many of the other emerging cities and towns. In 1848, the convention gave $100 each to pastors in Yazoo City, Jackson, Vicksburg and Grenada. That year, S.I. Caldwell, pastor of First Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds), reported the house of worship had been completed and that the membership had increased by 15 White members and 11 Black members. In 1853, I.T. Hinton, in the report of the Southern Baptist Domestic Mission Board, pointed out the need for placing missionaries in the state capital and the chief commercial towns, including Jackson, Vicksburg, Natchez, Biloxi and the Gulf Coast, all of which received aid. The Domestic Mission Board reported that the minister of the “church in Jackson, the capital received a commission from this Board. A large revival of religion has added very greatly to the strength of the church, however, rendering our aid unnecessary.”2

Natchez Baptist Church, Natchez (Adams) was restarted by Ashley Vaughn in 1837 and began to prosper under the pastorate of W.H. Anderson in the 1840s, but they were never able to build a meeting place of their own. They met at a Presbyterian church, at the courthouse, and at the Natchez Institute. In 1848, they called Rev. T.G. Freeman as pastor, but the church underwent a bitter split in 1849, and Freeman led in the formation of a new Baptist congregation, Wall Street Baptist, Natchez (Adams) in April 1850. The new congregation moved rapidly to build a sanctuary, breaking ground a month later at the corner of Wall Street and State Street, across from the Adams County Courthouse. They reported to the 1852 meeting of the Central Baptist Association that they had “erected a house of worship at a cost of $7,000 and paid for—the first ever owned by the Baptists in this city.” That year, Wall Street had 41 White members and three Black members, while Natchez Baptist Church had 34 White members and 412 Black members. Three years later, Wall Street had grown to 131 White and 105 Black members and held services four Sundays a month. Wall Street continued to grow, and proudly hosted the 1860 Mississippi Baptist Convention, whereas Natchez Baptist Church dissolved in 1857; its Black members were absorbed into Rose Hill Baptist Church, Natchez (Adams) an independent Black congregation that met on Madison Street. In 1918, Wall Street Baptist Church adopted the name First Baptist Church, Natchez, which remains to this day.3

By 1859, several town churches reported strong membership numbers to the state convention, including First Baptist Church, Jackson (Hinds) with 309 members, Canton Baptist Church, Canton (Madison) with 197 members, and Vicksburg Baptist Church, Vicksburg (Warren) with 160 members. An indirect result of the Baptists taking control of Mississippi College in 1850 was that a Baptist church was developed in Clinton. In the nine years afterward, Clinton Baptist Church, Clinton (Hinds) became the second largest of the five churches in the town. In May 1860, W. Jordan Denson described the church this way: “At present the Baptist Church of Clinton is enjoying one of those powerful revivals of religion, that she has so frequently been blessed with since the location of the college in that village. Last Sunday twenty-two were baptized, a large part students. Others will be baptized in two weeks—many others, we have reason to hope.”4

Although outside of the state, Mississippi Baptists took a special interest in reaching the city of New Orleans. The earliest Baptist churches in Louisiana were started by ministers from Mississippi, and those churches were affiliated with associations in Mississippi. New Orleans was an international port and was important to the entire Mississippi River Valley. In 1843, First Baptist Church, New Orleans was organized there with 10 members. It had great difficulty maintaining itself until Isaac T. Hinton became pastor. Under his leadership, the church made remarkable progress, increasing its membership from 27 to 122 members. A yellow fever epidemic in 1847 took the life of the pastor and many members, after which the church declined rapidly, and in 1851 the congregation lost its building to its creditors. The Mississippi Baptist Convention was distressed at this news and adopted resolutions urging the Southern Baptist Convention to help raise funds for a new church building in New Orleans. Several members of the convention made donations or pledges for this project. Finally, in 1861, First Baptist Church, New Orleans had another sanctuary.5

Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, to be published in 2025.

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Pearl River Baptist Association, 1860; U.S. Census, “Population of the United States in 1860: Mississippi,” accessed on the Internet 30 April 2022 at https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-22.pdf.

2 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1848, 13.

3 Robert C. Rogers, “From Alienation to Integration: A Social History of Baptists in Antebellum Natchez, Mississippi” (Th.D. diss.,, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, 1990), 53-59.

4 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1859, 14-15; 1860, 37.

5 Glen Lee Greene, House Upon a Rock: About Southern Baptists in Louisiana (Alexandria, LA: Executive Board of the Louisiana Baptist Convention, 1973), 41-51, 81-84; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1852, 31; Baptist Record, June 5, 1969.

Book review: “Baptist Successionism: A Critical Review”

W. Morgan Patterson is a Southern Baptist historian, educated at Stetson University, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and Oxford University. This book was published in 1979, but I recently picked it up and read it in one day.

This is a concise book (four chapters, 75 pages) that analyzes the failures of the sloppy historical research of Baptists, such as Landmarkists, who believe Baptist churches are in a direct line of succession from New Testament times. The introduction explains there are four different variations of successionist writers, from those who believe they can demonstrate it and that is necessary, to those who believe neither. Chapter one explains how the successionist view was not that of the earliest Baptists, but in the 19th century it was formulated by G.H. Orchard and popularized by J.R. Graves. Chapter two shows how the successionist writers misused their sources. Chapter three shows their poor logic. Chapter four exams some of the motivations behind this erroneous view. The conclusion sums up the book, noting that the successionist view was predominant in the 19th century, but thanks to bold historians like William Whitsitt, whose research debunked the theory in the 1890s, the successionist view became a minority position among Baptist historians in the 20th century.

Patterson is scholarly historian, and he may assume a little too much about the historical knowledge of the reader when he refers to the Münster incident on page 22 without explaining that this was a violent takeover of the city of Münster, Germany in 1534 by an Anabaptist fringe group that came to be associated with Anabaptists and Baptists in the minds of their opponents, and he refers to the Whitsitt controversy on page 24 without explaining the controversy until later.

Patterson could have made his argument stronger by giving more specific details about the heretical beliefs of groups claimed by successionist writers to be Baptists, such as the Donatists, Paulicians, Cathari, etc.

While Patterson’s book is concise, it is substantive, and his reasons are sound. This is an effective critique.

OTD in 1973: Earl Kelly leads Mississippi Baptists

On this day, November 14, 1973, Ernest Earl Kelly became executive director-treasurer of the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board. Kelly was baptized and ordained by the Cherry Creek Baptist Church in Pontotoc County, which was also the home church of J.B. Gambrell, the first executive of the MBCB in 1885. Kelly met his wife, Amanda Harding, when he was associate pastor of Calvary Baptist Church, Tupelo. Active in state convention affairs, Kelly had been pastor of First Baptist Church, Holly Springs for 14 years, and Ridgecrest Baptist Church, Jackson for six years before his election as the executive of the MBCB.

Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State, expected publication date in 2025.

The Presbyterian spy in the Baptist Church

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

The first Baptist church in Mississippi not only faced persecution from the Catholic church but was infiltrated by a Presbyterian spy.

In the 1790s the Spanish controlled the Natchez District, outlawing all public worship that was not Roman Catholic. However, in 1791, Baptist preacher Richard Curtis, Jr. organized a church on Coles Creek, 20 miles north of Natchez, later known as Salem Baptist Church. The Spanish governor, Don Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, allowed private Protestant worship, hoping to win them over to Catholicism. However, when the priests in Natchez complained of the public worship of the Baptist congregation, Gayoso arrested Curtis in April 1795, and threatened to confiscate his property and expel him from the district if he didn’t stop. Curtis agreed, but he and his congregation decided that didn’t prohibit them from having prayer meetings and “exhortation.” Curtis even performed a wedding in May for his niece but did so secretly.

Sometime in 1795, Ebenezer Drayton was sent by Governor Gayoso to infiltrate the Baptist meetings and send back reports. He reported that at first the Baptists were “afraid of me, and they immediately guessed that I was employed by Government, which I denied.” However, he convinced them that his “feelings were much like theirs… my being of the Protestant Sect called Presbyterians and they of the Baptist.” Thus reassured, they allowed Drayton to attend their meetings, but Drayton wrote letters informing the Spanish “Catholic Majesty,” as he called him, of their activities.

Thanks to Drayton, the Spanish learned that Curtis started to go back to South Carolina, but the congregation sent four men to chase him down and insist he stay and preach to them. Considering this God’s will, Curtis returned and continued to preach. Drayton reported that Curtis agonized over his decision to stay, but told his congregation, “God says, fear not him that can kill the body only, but fear him that can cast the soul into everlasting fire… I am not ashamed not afraid to serve Jesus Christ… and if I suffer for serving him, I am willing to suffer… I would not have signed that paper if I had then known that it is the will of God that I should stay here.”

Drayton had a low opinion of Curtis and the Baptists. He wrote that the Baptists “are weak men of weak minds, and illiterate, and too ignorant to know how inconsistent they act and talk, and that they are only carried away with a frenzy or blind zeal about what they know not what…” However, Curtis seemed sharp enough to realize there was spy among them, because in July 1795, he published a letter in Natchez, explaining why he stayed, defending his religious freedom, and saying he was deeply hurt by “the malignant information against us, laid in before the authority by some who call themselves Christians.”

Thanks to their spy, the Spanish knew exactly when and where the congregation met. In August 1795, they sent a posse to arrest Curtis and two of his converts, but they fled to South Carolina, where they remained until the Spanish were forced by American authorities to leave the Natchez District.

Dr. Rogers is the author of a new history of Mississippi Baptists, to be published in 2025.

Mississippi Baptist ministers to the Confederate Army during the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although not all white Baptists in Mississippi supported secession from the Union, they overwhelmingly supported the Confederate Army once the Civil War began. They especially felt the call to give spiritual support to the soldiers.

Mississippi’s legislature made ministers exempt from military service, but many of them volunteered for the military as chaplains, and others took up arms as soldiers. The Strong River Association sent two of their ministers to be chaplains in the Confederate Army: Rev. Cader Price to the Sixth regiment of the Mississippi Volunteers, and J. L. Chandler to the Thirty-Ninth.1 During this time, Baptist pastor H. H. Thompson served as a chaplain among the Confederate troops in southwest Mississippi. Thompson was the pastor of Sarepta Church in Franklin County, and simultaneously served as a chaplain to Confederate soldiers. In July 1862, Sarepta Church recorded in its minutes the resignation of Pastor Thompson due to poor health: “Resolved, that we accept the Bro. Thompson’s resignation but regret to part with him, as we found in him a faithful pastor, warm friend and devoted Christian, the cause of his resignation bad health. He has been laboring for some time under [handwriting illegible] and his service in the camps of the Army increased it to such extend that he sought medical advice which was that he should resign his pastoral labors.” 2

Chaplains actively proclaimed the gospel among the Confederate soldiers in Mississippi and Mississippians preached and heard the gospel as they fought in the war throughout the South. Matthew A. Dunn, a farmer from Liberty in Amite County, joined the State militia. From his military base in Meridian, Dunn wrote a letter to his wife in October 1863 that described nightly evangelistic meetings: “We are haveing [sic] an interesting meeting going on now at night—eight were Babtized [sic] last Sunday.” Sarepta Church in Franklin County recorded that a chaplain in the Confederate Army baptized one of their own who accepted Christ while on the warfront: “Thomas Cater having joined the Baptist Church whilst in the Confederate Army and have since died.” The certificate said he was baptized March 13, 1864, in Virginia by Chaplain Alexander A. Lomay, Chaplain, 16th Mississippi Regiment.3

One of the Confederate soldier/preachers would later become president of the Mississippi Baptist Convention and founder of Blue Mountain College. Mark Perrin Lowrey was a veteran of the Mexican War, then a brick mason who became a Baptist preacher in 1852. When the Civil War began, he was pastor of the Baptist churches at Ripley in Tippah County and Kossuth in Alcorn County. Like many of his neighbors in northeast Mississippi, he did not believe in slavery, yet he went to Corinth and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He was elected colonel and commanded the 32nd Mississippi Regiment. Lowrey commanded a brigade at the Battle of Perryville, where he was wounded. Most of his military career was in Hood’s campaign in Tennessee and fighting against Sherman in Georgia. He was promoted to brigadier-general after his bravery at Chickamauga, and played a key role in the Confederate victory at Missionary Ridge. In addition to fighting, he preached to his troops. One of his soldiers said he would “pray with them in his tent, preach to them in the camp and lead them in the thickest of the fight in the battle.” Another soldier said Lowrey “would preach like hell on Sunday and fight like the devil all week!” He was frequently referred to as the “fighting preacher of the Army of Tennessee.” He led in a revival among soldiers in Dalton, Georgia, and afterwards baptized 50 of his soldiers in a creek near the camp. After the war, the Mississippi Baptist Convention elected Lowrey president for ten years in a row, 1868-1877.4

First Baptist Church of Columbus, perhaps the most prosperous Baptist congregation in the State, lost many members to the war, and many wealthy members lost their fortunes. Their pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale, resigned the church in 1863 to become an evangelist among the Confederate troops. He often preached to an entire brigade, and in one case, preached a sermon on “The General Judgment” to 6,000 soldiers of General Claiborne in Dalton, Georgia, baptizing 80 soldiers after the sermon, and baptizing 60 more the next week. After the Union Army under Sherman attacked, he was no longer able to preach to the soldiers, and returned home to Columbus.5

NOTES:

1 John T. Christian, “A History of the Baptists of Mississippi,” Unpublished manuscript, 1924, 186; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1861, 13-16.

2 John K. Bettersworth, “The Home Front, 1861-1865,” in A History of Mississippi, vol. 1, ed. by Richard Aubrey McLemore (Hattiesburg: University & College Press of Misssissippi, 1973), 532-533; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, July 1862; Minutes, Bethesda Baptist Church, Hinds County, Mississippi, October 18, 1862.

3 Matthew A. Dunn to Virginia Dunn, October 13, 1863. Matthew A. Dunn and Family Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, October 1865.

4 Christian, 135, 197; Robbie Neal Sumrall, A Light on a Hill: A History of Blue Mountain College (Nashville: Benson Publishing Company, 1947), 6-12.

5 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 184-185.

When contemporary Christian music was introduced to Mississippi Baptists

Article copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although typical worship services were still dominated by hymns and Southern gospel songs, the “Jesus people” movement introduced contemporary music to the church in the early 1970s. Throughout the 1970s, it became common for Baptist youth choirs to go on tour, singing contemporary music at other churches. In December 1971, First Baptist Church, Long Beach, advertised in The Baptist Record that their youth choir would premier an hour-long youth musical composed by Otis Skillings, entitled “Love.” One of the most popular musicals, called “Celebrate Life,” was published by Broadman Press, the Southern Baptist publishing house. In 1972, Plantersville Baptist Church had one of the youngest choirs, ages 7-12, singing contemporary religious music on tour at churches in Mississippi in Alabama. One of the early groups popular among Mississippi Baptist youth was a hybrid between a college-aged choir and brass band called “Truth,” organized by Roger Breland from Mobile, Alabama. In 1971, Truth took the Mississippi Baptist Youth Night by storm, and were invited back in 1972 “by popular demand.”1

In 1975, Broadman Press published a new Baptist Hymnal which included some contemporary songs and spirituals, in addition to traditional hymns. Dan Hall, director of the Church Music Department of the Mississippi Baptist Convention, was one of the first to endorse the new hymnal. However, music styles became a divisive issue among Mississippi Baptists, as illustrated by months of debate in The Baptist Record in 1985. After a letter in August 1985 complained that “Christian rock” music was “demonic.” Soon letters were published every week, alternately defending and attacking “Christian rock” music. The debate continued for months until Randy Weeks of Columbus wrote a letter to the editor in rhyme, asking: “To rock and roll/ must I sell my soul/ as some insinuate?… For once more it seems/ humanity screams/ for answers to save all their lives/ and we spend our days/ thinking up ways/ to criticize Christians who jive.”2

SOURCES:

1 The 1973 annual meeting of the Mississippi Baptist Convention listed the congregational songs at each session, all of which were traditional hymns, such as “All Hail the Power of Jesus Name,” “Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus,” and the Bill Gaither Southern gospel song, “He Touched Me.” Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1973, 39-41; The Baptist Record, December 16, 1971, 3; December 27, 1971, 7; October 19, 1972, 7; December 14, 1972, 1, 2.

2 The Baptist Record, March 6, 1975, 1; August 22, 1985, 11; August 29, 1985, 8; September 5, 1985, 6; September 12, 1985, 9; September 19, 1985, 9; October 31, 1985, 6; November 14, 1985, 5.

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.

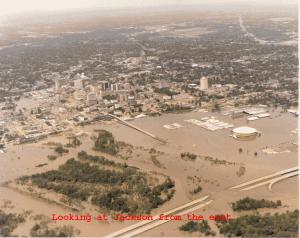

Mississippi Baptist responses to natural disasters in late 20th century

Article copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Hardly a year passed without a story of a natural disaster or fire destroying a church in Mississippi in the late 20th century, yet each time Baptists responded with a helping hand. Mississippi Baptists began to organize and prepare themselves to respond to disasters. Soon after Hurricane Camille in 1969, Southern Baptists began discussing a more efficient way to respond to disasters. The Mississippi Baptist Convention put together a van with supplies in the 1970s, and assigned the work to the Brotherhood Department.

The Pearl River “Easter Flood” shut down the city of Jackson in April 1979. Some 15,000 residents had to be evacuated by Thursday, April 17, and downtown was cordoned off. Although no Mississippi Baptist churches were flooded, the Baptist Building in Jackson had to close for a time. At least 500 Baptist families had flooded homes, particularly members of Colonial Heights, Broadmoor, First Baptist, Northminster and Woodland Hills Baptist churches. Several hundred male student volunteers from Mississippi College were bussed from their dorms in Clinton to Flowood to work on the levee. The Mississippi Baptist Disaster Relief van was on the scene, serving hot meals to 1,500 people. For weeks, volunteers met every Saturday to do repairs, and the MBCB executive committee endorsed a statewide offering for churches to aid in flood relief.1

Hurricane Frederic damaged churches in the Pascagoula area in September 1979. In September 1985, Hurricane Elena did damage estimated at $3 million to churches and Baptist facilities all over the Gulf Coast. Griffin Street Baptist Church in Moss Point had its back wall blown out. The pastor, Athens McNeil, quipped, “We’re open to the public… literally.” Elena also damaged Gulfshore Baptist Assembly, the seamen’s center, and it caused $1.5 million in damage to William Carey College on the Coast. Baptist relief units were on the scene right away, working in conjunction with the Red Cross. A number of Baptist churches served as shelters; some 250 people stayed at First Baptist Church, Pascagoula.2

A deadly tornado hit churches in Pike and Lincoln counties in January 1975, and another twister damaged churches in Water Valley in April 1984. The most destructive tornado during this time was the one that hit Jones County on Saturday, February 28, 1987. Five Baptist churches had property damage, and members of five other Baptist churches had personal property damage. “I have never seen such damage since I left the battlefield in Europe as I saw in Jones County,” wrote Don McGregor, editor of The Baptist Record. Immediately, the Mississippi Baptist Brotherhood Department began calling churches across the State for volunteers. The day after the Jones tornado hit, 325 volunteers, representing 55 churches, arrived at the Jones County Baptist Association to serve. Hundreds more volunteers arrived during the week; eventually 1,000 people helped with clean-up and relief supplies.3

SOURCES:

1 The Baptist Record, April 19, 1979, 1; April 26, 1979, 1; May 10, 1979, 1; May 17, 1979, 1; Author’s personal memory as a student at Mississippi College working on the levee for 17 hours in one day to stop floodwaters.

2 The Baptist Record, September 12, 1985, 3; September 20, 1979, 1; September 29, 1979, 1; September 19, 1985, 1, 3, 5.

3 The Baptist Record, January 16, 1975, 1, 2; March 5, 1987, 3; March 12, 1987, 3, 4; March 19, 1987, 2.

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a history of Mississippi Baptists.

How Mississippi Woman’s College became William Carey College

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

In the 1950s, the Mississippi Baptist Convention had to make a decision about what to do with Mississippi Woman’s College in Hattiesburg. Since reopening in 1947 under the leadership of Dr. Irving E. Rouse, the college enrollment grew steadily from 76 students to 149 by 1951. However, many felt that the all-female status of the college hindered its potential to grow. During debate over the issue, Sue Bell Johnson, wife of former president Johnson, prayed, “Lord, if Woman’s College can help bring in the Kingdom, save it.” In 1953, the Mississippi Baptist Education Commission presented the State Convention with two choices regarding the college: either close it, or make it co-educational. Messengers voted overwhelmingly to keep it open and make it co-educational. Then messengers took another vote on whether the college should be a junior college or a senior college, and by a vote of 304 to 291, they voted to make it a senior college. Knowing it could no longer be called “Woman’s College,” President Rouse suggested the name William Carey College, in honor of the 18th century English Baptist missionary to India who became the father of modern missions, and the new name was approved by the faculty and trustees. According to tradition, Rouse meditated in the forest adjacent to the college, and there felt inspired to name the school after the missionary. Thus, the college inherited the famous motto of William Carey, “Expect great things from God, attempt great things for God.”1

Even before Mississippi Woman’s College adopted its new name, the school began immediately to prepare for male students, erecting a male dormitory that opened in the fall of 1954. The administration knew that a quick way to bring in male students was by creating football, baseball, basketball and track teams. Les De Vall, head coach of Hinds Junior College in Raymond, was hired as the football coach. Billy Crosby, a member of the football and baseball teams, said that one day President Rouse asked if he would be interested in playing for Mississippi Woman’s College. Crosby thought, “I could just see the headlines: ‘The Skirts Lose Again.’” Nevertheless, Billy and 35 other players showed up that fall at the then-renamed William Carey College. With the addition of male students, the total enrollment in the fall of 1954 was 315 students. The football team posted winning seasons in its two years of competition, 1954 and 1955. An even greater spiritual victory occurred when Dr. Andy Tate, dean of men, led several of the football players to faith in Christ. These conversions sparked a revival in the men’s dormitory, and over 100 male students made professions of faith. Some of the athletes became ministers. The prayers of Sue Bell Johnson were already being answered.2

Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State (Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, 2025). The book is not sold in stores or on Amazon, but you may get a copy by making a donation ($15 suggested) to the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission at this link, and tell them at the bottom of the form how many copies of the book you want: https://mbcb.org/historicalcommission/

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1951, 114; 1953, 45; Donna Duck Wheeler, William Carey College: The First 100 Years (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006), 43, 48, 49; The Baptist Record, May 13, 1954, 1; October 14, 2004, Special Supplement Celebrating the Jubilee of William Carey College.

2 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1954, 113; Wheeler, 51, 53.

How Mississippi Baptist churches struggled during the Great Depression

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

During the Great Depression, nearly every church had financial struggles, whether the church was large or small. First Baptist Church in Natchez had already begun a new building when the stock market crashed, dedicating their building in 1930. Unfortunately, the debt of approximately $25,000 proved a heavy burden during the depression, and it took them until 1945 to pay it off. The pastor, W. A. Sullivan, asked that his own salary be cut, and the difference be applied to the church debt. Despite this and other sacrifices, in January 1932 the church was unable to pay the interest on their loan. To avoid default, the church took out another loan to pay the interest on the first loan. It was not until 1939 that the financial situation improved enough that they began to pay down the principal on the debt; it took the Natchez church until 1945 to get out of debt1

First Baptist Church in Clinton borrowed money to build a new building in 1923, but struggled to pay the debt, as it was a small church, with a large majority of the members being college students with little income. The Clinton church’s building debt was a third of its income when the Great Depression came, and the church had little means to pay. In April 1933, the deacons recommended that the pastor serve a month without pay, and that payments to the debt be deferred for six months, paying only the interest. It would be another ten years before they finally paid the debt.2

Calvary Baptist Church in Jackson was a large congregation of 1600 members in 1930, but many members lost their jobs and left Jackson seeking work elsewhere. The hard times caused them to appoint a five-man committee to present a plan to cut expenses. At first, they proposed moderate cuts, eliminating salaries for choir members, getting rid of one telephone, and urging “strictest economy” in electricity and water use. But as offerings continued to fall, they slashed other salaries and stopped purchasing Sunday school literature.3

When the Great Depression started, C. J. Olander was pastor of several churches in the Rankin County area, including First Baptist of Brandon, Bethel, Fannin and Pisgah churches, and he started the church at Flowood. Olander wrote later, “The depression became so severe that the members [at Flowood] moved out for the time being and came back and reorganized.” The Brandon Church paid him $450 a year. To supplement his income, Olander sold milk to townspeople and kept a good garden for food. In 1935, Olander went to the Delta to pastor five churches at once, even though a friend warned him that if he went there, “you will never be heard of again and the folk will starve you to death.” Olander said, “It was bad, it was bankrupt, yet today as a result of that ministry there are six full time churches. There was Morgan City, Tchula, Blaine, Cruger, Sidon and Harmony.”4

Some churches managed to thrive despite the Depression. A. L. Goodrich was called to pastor First Baptist Church, Pontotoc, just 30 days before the banks closed. Rather than let it dampen his spirits, Goodrich focused on sharing the gospel and helping his community. The energetic pastor joined local civic clubs, he took leadership positions in his Association and the State Convention, and he organized the “Pontotoc Cotton Plan” to give hundreds of dollars to the Mississippi Baptist Orphanage. God blessed the church with an increase of 232 members during his years as pastor, 1931-1935. The Pontotoc church’s Sunday night worship attendance was equal to morning worship; they started three choirs, paid off an old debt and installed a pipe organ.5

Dr. Rogers is the author of Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State (Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, 2025). The book is not sold in stores or on Amazon, but a copy can be obtained by making a donation ($15 suggested) to the Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission at this site: https://mbcb.org/historicalcommission/ .

SOURCES:

1 “A History of First Baptist Church, Natchez, Mississippi, 1817-2000,” Unpublished document, Archives, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission, 17-19; Daniel A. Wynn, “History of First Baptist Church of Natchez,” in Forward to Freedom: The 175th Anniversary Celebration, First Baptist Church, Natchez, Mississippi, April 26, 1992.

2 Charles E. Martin, A Heritage to Cherish: A History of First Baptist Church, Clinton, Mississippi, 1852-2002 (Nashville: Fields Publishing, Inc., 2001), 93-96.

3 Randy J. Sparks, Religion in Mississippi (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 183.

4 Tom J. Nettles, The Patience of Providence: A History of First Baptist Church Brandon, Mississippi, 1835-1985 (First Baptist Church, Brandon, Mississippi, 1989), 69, 72-73.

5 The Baptist Record, January 3, 1935, 5.

The Mississippi Delta preacher and his train ticket

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Mississippi Baptists are primarily a rural people, and during the Great Depression, many of these churches could only afford to pay their pastors with vegetables, chickens, eggs and meat from their gardens and farms. The only way that many small country churches could find a pastor was to have one come once or twice a month, and share him with other churches. In 1930, Will Turner, a leader from Straight Bayou Baptist Church in Sharkey County talked to C. C. Carraway, the young pastor of Midnight Baptist Church. Turner asked Carraway if he would preach at Straight Bayou, as well. Carraway, who was a student at Mississippi College, said he would. Turner asked how much his round-trip train ticket cost from Clinton to Midnight, and he said it was $4.28. Turner said, “Then that’s what we’ll pay you each time you come.”

Source: “Straight Bayou Baptist Church: The First Hundred Years, 1891-1991,” Straight Bayou Baptist Church, Anguilla, Miss., Unpublished document, Archives, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission, 12.