Blog Archives

Mississippi Baptist ministers to the Confederate Army during the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

Although not all white Baptists in Mississippi supported secession from the Union, they overwhelmingly supported the Confederate Army once the Civil War began. They especially felt the call to give spiritual support to the soldiers.

Mississippi’s legislature made ministers exempt from military service, but many of them volunteered for the military as chaplains, and others took up arms as soldiers. The Strong River Association sent two of their ministers to be chaplains in the Confederate Army: Rev. Cader Price to the Sixth regiment of the Mississippi Volunteers, and J. L. Chandler to the Thirty-Ninth.1 During this time, Baptist pastor H. H. Thompson served as a chaplain among the Confederate troops in southwest Mississippi. Thompson was the pastor of Sarepta Church in Franklin County, and simultaneously served as a chaplain to Confederate soldiers. In July 1862, Sarepta Church recorded in its minutes the resignation of Pastor Thompson due to poor health: “Resolved, that we accept the Bro. Thompson’s resignation but regret to part with him, as we found in him a faithful pastor, warm friend and devoted Christian, the cause of his resignation bad health. He has been laboring for some time under [handwriting illegible] and his service in the camps of the Army increased it to such extend that he sought medical advice which was that he should resign his pastoral labors.” 2

Chaplains actively proclaimed the gospel among the Confederate soldiers in Mississippi and Mississippians preached and heard the gospel as they fought in the war throughout the South. Matthew A. Dunn, a farmer from Liberty in Amite County, joined the State militia. From his military base in Meridian, Dunn wrote a letter to his wife in October 1863 that described nightly evangelistic meetings: “We are haveing [sic] an interesting meeting going on now at night—eight were Babtized [sic] last Sunday.” Sarepta Church in Franklin County recorded that a chaplain in the Confederate Army baptized one of their own who accepted Christ while on the warfront: “Thomas Cater having joined the Baptist Church whilst in the Confederate Army and have since died.” The certificate said he was baptized March 13, 1864, in Virginia by Chaplain Alexander A. Lomay, Chaplain, 16th Mississippi Regiment.3

One of the Confederate soldier/preachers would later become president of the Mississippi Baptist Convention and founder of Blue Mountain College. Mark Perrin Lowrey was a veteran of the Mexican War, then a brick mason who became a Baptist preacher in 1852. When the Civil War began, he was pastor of the Baptist churches at Ripley in Tippah County and Kossuth in Alcorn County. Like many of his neighbors in northeast Mississippi, he did not believe in slavery, yet he went to Corinth and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He was elected colonel and commanded the 32nd Mississippi Regiment. Lowrey commanded a brigade at the Battle of Perryville, where he was wounded. Most of his military career was in Hood’s campaign in Tennessee and fighting against Sherman in Georgia. He was promoted to brigadier-general after his bravery at Chickamauga, and played a key role in the Confederate victory at Missionary Ridge. In addition to fighting, he preached to his troops. One of his soldiers said he would “pray with them in his tent, preach to them in the camp and lead them in the thickest of the fight in the battle.” Another soldier said Lowrey “would preach like hell on Sunday and fight like the devil all week!” He was frequently referred to as the “fighting preacher of the Army of Tennessee.” He led in a revival among soldiers in Dalton, Georgia, and afterwards baptized 50 of his soldiers in a creek near the camp. After the war, the Mississippi Baptist Convention elected Lowrey president for ten years in a row, 1868-1877.4

First Baptist Church of Columbus, perhaps the most prosperous Baptist congregation in the State, lost many members to the war, and many wealthy members lost their fortunes. Their pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale, resigned the church in 1863 to become an evangelist among the Confederate troops. He often preached to an entire brigade, and in one case, preached a sermon on “The General Judgment” to 6,000 soldiers of General Claiborne in Dalton, Georgia, baptizing 80 soldiers after the sermon, and baptizing 60 more the next week. After the Union Army under Sherman attacked, he was no longer able to preach to the soldiers, and returned home to Columbus.5

NOTES:

1 John T. Christian, “A History of the Baptists of Mississippi,” Unpublished manuscript, 1924, 186; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1861, 13-16.

2 John K. Bettersworth, “The Home Front, 1861-1865,” in A History of Mississippi, vol. 1, ed. by Richard Aubrey McLemore (Hattiesburg: University & College Press of Misssissippi, 1973), 532-533; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, July 1862; Minutes, Bethesda Baptist Church, Hinds County, Mississippi, October 18, 1862.

3 Matthew A. Dunn to Virginia Dunn, October 13, 1863. Matthew A. Dunn and Family Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi; Minutes, Sarepta Baptist Church, Franklin County, Mississippi, October 1865.

4 Christian, 135, 197; Robbie Neal Sumrall, A Light on a Hill: A History of Blue Mountain College (Nashville: Benson Publishing Company, 1947), 6-12.

5 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 184-185.

Rev. T. C. Teasdale’s daring adventure with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most amazing but lesser-known stories of the Civil War is how a Mississippi Baptist preacher got both Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln to agree to help him sell cotton across enemy lines in order to fund an orphanage. Although the plan collapsed in the end, the story is still fascinating.

Since over 5,000 children of Mississippi Confederate soldiers were left fatherless, an interdenominational movement started in 1864 to establish a home for them. On October 26, 1864, the Mississippi Baptist Convention accepted responsibility for the project. The Orphans’ Home of Mississippi opened in October 1866 at Lauderdale, after considerable effort, especially by one prominent pastor, Dr. Thomas C. Teasdale.1

Rev. Teasdale was in a unique position to aid the Orphans’ Home, because of his influential contacts in both the North and South. A New Jersey native, he came to First Baptist Church, Columbus, Mississippi in the 1850s from a church in Washington, D.C. When the Civil War erupted, he left his church to preach to Confederate troops in the field. In early 1865, he returned from preaching among Confederate soldiers to assist with the establishment of the Orphans’ Home of Mississippi. He launched a creative and bold plan to raise money and solve a problem of donations. A large donation of cotton was offered to the orphanage, and the cotton could bring 16 times more money in New York than in Mississippi, but how could they sell it in New York with the war still raging? Since Teasdale had been a pastor in Springfield, Illinois and Washington, D.C. and had preached to the Confederate armies, he was personally acquainted with both U.S. President Abraham Lincoln (from Illinois) and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and many of their advisers. In February and March 1865, he set out on a dangerous journey by horseback, boat, railroads, stagecoach and foot, dodging Sherman’s march through Georgia, crossing through the lines of the armies of both sides, and conferred in Richmond and Washington, seeking permission from both sides to sell the cotton in New York for the benefit of the orphanage.2

Confederate President Davis readily agreed, and on March 3, 1865, Davis signed the paper granting permission for the sale. Next, Dr. Teasdale slipped across enemy lines and entered Washington, a city he knew well, since he was a former pastor in the city. He waited in line for several days for an audience with President Lincoln, but he could not get in, since government officials in line were always a higher priority than a private citizen. Finally, he sent a note to Mr. Lincoln, whom he knew when they both lived in Springfield, Illinois, saying that he was now a resident of Mississippi and that he was there on a mission of mercy. Lincoln received him, and he listened to the plea for cotton sales to support the orphanage, but the president was skeptical. Why should he help Mississippi, a State in rebellion against the United States? In his autobiography, Teasdale records Lincoln’s words: “We want to bring you rebels into such straits, that you will be willing to give up this wicked rebellion.” Dr. Teasdale replied, “Mr. President, if it were the big people alone that were concerned in this matter, I should not be here, sir. They might fight it out to the bitter end, without my pleading for their relief. But sir, when it is the hapless little ones that are involved in this suffering, who, of course, who had nothing to do with bringing about the present unhappy conflict between the sections, I think it is a very different case, and one deserving of sympathy and commiseration.” Lincoln instantly said, “That is true; and I must do something for you.” With that, Lincoln signed the paper, granting permission for the sale. It was March 18, 1865. However, a few weeks later, on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army to Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant. By the time Teasdale returned home, the war was over, the permission granted by Jefferson Davis no longer had authority, Lincoln was assassinated, and Teasdale abandoned his plans. Teasdale said, “This splendid arrangement failed, only because it was undertaken a little too late.” Undaunted, Dr. Teasdale volunteered as a fundraising agent for the orphanage and staked his large private fortune on its success. Rarely has there been a more daring donor to a Christian cause!3

Dr. Rogers is currently writing a new history of Mississippi Baptists.

SOURCES:

1 Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 12-17; 1867, 29-31.

2 Jesse L. Boyd, A Popular History of the Baptists in Mississippi (Jackson: The Baptist Press, 1930), 131.

3 Thomas C. Teasdale, Reminiscences and Incidents of a Long Life, 2nd ed. (St. Louis: National Baptist Publishing Co., 1891), 173-174, 187-203; Boyd, 130-132; Minutes, Mississippi Baptist Convention, 1866, 3, 14-16.

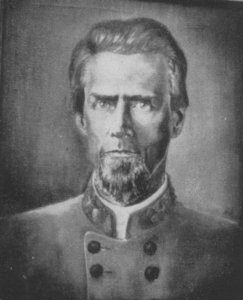

M.P. Lowrey, Mississippi’s “fighting preacher” in the Civil War

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers and the Mississippi Baptist Convention Board.

One of the most interesting Mississippi veterans of the Civil War was M. P. (Mark Perrin) Lowrey. Lowrey was a veteran of the Mexican War, then a brick mason who became a Baptist preacher in 1852. When the Civil War began, he was pastor of the Baptist churches at Ripley in Tippah County and Kossuth in Alcorn County. Like many of his neighbors in northeast Mississippi, he did not believe in slavery, yet he went to Corinth and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He was elected colonel and commanded the 32nd Mississippi Regiment. Lowrey commanded a brigade at the Battle of Perryville, where he was wounded. Most of his military career was in Hood’s campaign in Tennessee and fighting against Sherman in Georgia. He was promoted to brigadier-general after his bravery at Chickamauga, and played a key role in the Confederate victory at Missionary Ridge. In addition to fighting, he preached to his troops. One of his soldiers said he would “pray with them in his tent, preach to them in the camp and lead them in the thickest of the fight in the battle.” Another soldier said Lowrey “would preach like hell on Sunday and fight like the devil all week!” He was frequently referred to as the “fighting preacher of the Army of Tennessee.” He led in a revival among soldiers in Dalton, Georgia, and afterwards baptized 50 of his soldiers in a creek near the camp. After the war, Lowrey founded Blue Mountain College in Tippah County, and the Mississippi Baptist Convention elected Lowrey president for ten years in a row, 1868-1877.

SOURCES:

John T. Christian, “A History of the Baptists of Mississippi,” Unpublished manuscript, Mississippi Baptist Historical Commission Archives, Clinton, Mississippi, 1924, 135, 197; Robbie Neal Sumrall, A Light on a Hill: A History of Blue Mountain College (Nashville: Benson Publishing Company, 1947), 6-12.

Dr. Rogers is currently revising and updating A History of Mississippi Baptists.

Tearing down statues– where does it end?

Protesters in San Francisco have pulled down a bust of Ulysses Grant, the former U.S. president and Union general who defeated the Confederates, because Grant married into a slave-owning family. They also pulled down other statues, including that of Francis Scott Key (pictured above), who wrote the U.S. national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner,” since Key owned slaves.

I readily agree that slavery was and is reprehensible, and the Confederates were traitors to the Union. I also agree that statues of many such historical people need to be removed to museums, not glorified front and center in our parks and courthouses. But where does this sort of thing end? What person, past or present, is without character flaws?

I wonder if these same protesters would be willing to tear down a statue of Charles Darwin, since he was a racist who said Africans were less evolved than white people? I wonder if these same protesters would be willing to deface a statue of John F. Kennedy, since he was reportedly an adulterer?

Interestingly, some of those people of the past, if they were here today, would likely be shocked by the immoral practices of some of these modern protesters, some who may cohabitate outside of marriage or may have killed babies through abortion– but at least they didn’t own slaves, so they judge themselves righteous. How blind these self-righteous anarchists are, seeing the sins of the past but ignoring the sins of the present.

These modern moralists do not see how similar their vandalism is to ISIS fighters who tore down ancient statues in the Middle East because they were “pagan.” These revolutionaries do not see how their onrush to destroy any and every injustice in the name of the people is similar to another revolution– the French revolution, a time when the revolutionaries were soon devouring each other for not being radical enough. Today’s radicals could read about it in their history books, but it seems they have torn out most of the pages.