Blog Archives

Book review: “Crusaders” by Dan Jones

Dan Jones. Crusaders: The Epic History of the Wars for the Holy Lands. Viking, 2019.

I have read several books on the Crusades, but this is the best I’ve read so far. Dan Jones has written numerous books on the Europeans in the Middle Ages, so this is his area of expertise. His work is thoroughly researched, but he also writes in an engaging style, opening most chapters with vignettes about colorful personalities, and he peppers the book with fascinating quotes and interesting details.

The title Crusaders (instead of “Crusades”) is deliberate, because, as Jones explains in his preface, he focuses on the personalities like Richard the Lionheart, telling stories of the combatants (mostly Christian, but he also gives coverage to prominent Muslim warriors, including a chapter on Saladin). Yet he tells the story in chronological order, which helps the reader to follow the facts.

With so much blood and horrendous violence, Jones could easily depict the Crusaders as pure evil, but as a good historian he leaves it to the reader to make moral judgments, even reminding the reader at times that as bad as the violence was, it was normal for all sides at that time in history. He simply tells the facts and quotes the sources that describe the characters, whether evil or holy, or, as many were, a mixture of both. The book truly helps the reader understand the reasons why the Crusades happened as they did by helping the reader understand life in the Middle Ages. Until I read this book, I didn’t fully understand why the Fourth Crusaders plundered Constantinople instead of invading Muslim territory, but now I understand the economic motivations of the Venetians.

The old adages about history repeating itself and not learning lessons from history are evident in these stories. One example is the defeat of the Fifth Crusade on the Nile River because they didn’t consider the geography of when the Nile would flood and stop their advance. Another example was how Emperor Frederick II was able to gain more by negotiation than the previous Crusaders had gained by war, because he spoke Arabic and was able to gain their trust.

Jones explains that the Crusades included the “Reconquista,” the seven hundred years of battles for Spain to retake the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims, which finally ended in 1492. Thus, instead of seeing the Crusades as a total failure, since the Crusaders were expelled from the Holy Land after the fall of Acre in 1291, he sees the battle for Spain as a success for the crusaders. He even cities numerous occasions when crusaders on their way to the Holy Land would stop off in Spain and help them win a battle, then sail on for Jerusalem. The author explains how, even as Europe lost interest in raising large international armies to fight Muslims in the Holy Land, the crusading spirit continued and degenerated into hunting down heretics in southern France, fighting pagan tribes in the Balkans, and even papal battles against Christian rulers who refused to submit to the pope.

I wish that Jones had explained more of the results of the Crusades. He does allude to how it gave power to the pope, and he ends the book by explaining the anti-Christian bitterness that remains among Muslims in the Middle East. He could have said more about how it affected Muslim treatment of Christian minorities in the Middle East, and how the contact opened doors of economic, cultural, and intellectual trade between East and West, even helping bring Arabic numerals and Aristotle’s philosophy to the West.

Sadly, Jones points out that the Crusades never fully ended, as Osama bin Laden referred to President George W. Bush as “the Chief Crusader… under the banner of the cross.” As ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi said, “the battle of Islam and its people against the crusaders and their followers is a long battle.”

Tearing down statues– where does it end?

Protesters in San Francisco have pulled down a bust of Ulysses Grant, the former U.S. president and Union general who defeated the Confederates, because Grant married into a slave-owning family. They also pulled down other statues, including that of Francis Scott Key (pictured above), who wrote the U.S. national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner,” since Key owned slaves.

I readily agree that slavery was and is reprehensible, and the Confederates were traitors to the Union. I also agree that statues of many such historical people need to be removed to museums, not glorified front and center in our parks and courthouses. But where does this sort of thing end? What person, past or present, is without character flaws?

I wonder if these same protesters would be willing to tear down a statue of Charles Darwin, since he was a racist who said Africans were less evolved than white people? I wonder if these same protesters would be willing to deface a statue of John F. Kennedy, since he was reportedly an adulterer?

Interestingly, some of those people of the past, if they were here today, would likely be shocked by the immoral practices of some of these modern protesters, some who may cohabitate outside of marriage or may have killed babies through abortion– but at least they didn’t own slaves, so they judge themselves righteous. How blind these self-righteous anarchists are, seeing the sins of the past but ignoring the sins of the present.

These modern moralists do not see how similar their vandalism is to ISIS fighters who tore down ancient statues in the Middle East because they were “pagan.” These revolutionaries do not see how their onrush to destroy any and every injustice in the name of the people is similar to another revolution– the French revolution, a time when the revolutionaries were soon devouring each other for not being radical enough. Today’s radicals could read about it in their history books, but it seems they have torn out most of the pages.

Book review: “A History of the Modern Middle East”

A

A History of the Modern Middle East by William L. Cleveland and Martin Bunton, 6th ed., (Westview Press, 2016).

This history does as the title promises, focusing more on the modern period of the Middle East, especially from the Ottoman Empire through 2015. The book covers the rise of ISIS but was written before the downfall of ISIS. It includes the Arab Spring of 2011, which Cleveland prefers to call the “Arab Uprisings.” It includes balanced discussions of areas from Turkey to Iran to the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt. It does not include neighboring countries such as the Sudan, North Africa or Afghanistan in the discussion, except where events there affect the Middle East proper, such as the Egyptian war in Sudan, the harboring of Osama bin Laden by the Taliban in Afghanistan, and the Arab uprisings that began in Tunisia and led to the downfall of Libya’s dictator, too.

The book gives much attention to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which is appropriate, as well as thorough coverage of the Kurdish problem of being a people without a homeland.

Perhaps due to his focus on the modern period, Cleveland passes over the Crusades with barely a mention, which I found peculiar, since modern Arabs like Osama bin Laden referred to Christians as the “Crusaders.”

While Cleveland strives to present a balanced report of both the positive and negative traits of each people and each personality, he appears to have certain biases. He clearly is sympathetic to the plight of the Palestinians verses the Jews, and is favorable to the Muslim worldview (for example, he blames Islam’s low view of women on the influences of the cultures neighboring the Arabs, and refers to the Muslim Brotherhood as “moderate”). Nevertheless, he does a good job of explaining the various sectarian and ethnic groups, such as the Sunni and Shi’a, and minority groups like Arab Christians, Assyrians, Yazidis, Druze, Alawites, etc.

Four key pieces to the Middle East puzzle

Copyright by Bob Rogers.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, country singer Alan Jackson wrote a hit song, asking, “Where were you when the world stopped turnin’ that September day?” One line in that song expressed how little most Americans understand the Middle East:

“I’m just a singer of simple songs

I’m not a real political man

I watch CNN, but I’m not sure I can tell you

The diff’rence in Iraq and Iran.”

So how does one piece together the puzzle of the Middle East? There are four important pieces to the puzzle that are key. Fit these four pieces in place, and you will get a good picture of why there is conflict in the Middle East:

1. Muslims are not all alike. Most Americans assume that all Muslims are the same. In fact, there are two major branches of Islam: Sunni and Shiite. They have different doctrines, and a long history of bitter conflict. On the Shiite side is Iran, southern Iraq, rebels in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza, and Bashar al-Assad, dictator of Syria. On the Sunni side is most of the rest of the Muslim world, including northern and western Iraq, the government in Yemen, the Islamic State (ISIS), the majority of Syria, and such large nations as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey. Now take a look at the map above. See the two geographical giants, Saudi Arabia and Iran? Saudi Arabia is Sunni, and Iran is Shi’a, and the two nations are in constant struggle against one another. See Iraq between them? As Iran seeks to extend it’s influence, Saudi Arabia opposes Iran, and places like Iraq and Yemen are the battleground.

2. Middle Easterners are not all Arabs. Most Americans assume all Middle Easterners are either Arabs or Jews. In fact, there are three other major ethnic groups in the Middle East that speak different languages and have different cultures: Turks, Kurds and Persians. Jews dominate Israel, and most of the southern part of the Middle East is Arab, including Egypt and Saudi Arabia, but as one goes north, there are other ethnicities. Turks are the majority in Turkey, but some 20% of Turkey are Kurds, and Kurds are concentrated in southeastern Turkey. Kurds have a semi-autonomous self-rule in northern Iraq, and Kurds in northern Syria have dominated that region as they defeated ISIS during Syria’s Civil War. Iran is primarily Persian, but has Kurds in its western region. There are also ethnic groups in the Middle East like the Coptic Christians of Egypt, Druze in Lebanon, Assyrian Christians in Iraq, and Yazidis in Iraq (who speak the Kurdish language but have their own religion that blends Islam with Christianity and Zoroastrianism. ISIS considers the Yazidis to be demon-worshipers.).

3. Many of their national boundaries were forced on the Middle East. Before World War I, the Ottoman Empire ruled a vast area that included what is now Turkey, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Saudi Arabia (even Egypt was subject to the Ottoman Empire). The Ottomans sided with Germany in WWI, and lost everything but Turkey after the war. Europeans, who didn’t understand the region, drew new national boundaries to create many of the nations we now have in that region, most notably splitting up the region inhabited by 25 million Kurds into parts of Iran, Turkey, Iraq and Syria. Thus the Kurds have been a mistreated minority in their own homeland. What is more, the Europeans created a new nation called Iraq, out of three former Ottoman provinces that had no natural commonality, with Kurds in the north, Sunni Arabs in the middle, and Shi’a Arabs in the south. No wonder Iraq is in constant conflict.

4. There are two sides to the story in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Before World War I, the population of the Ottoman province of Palestine was about 90% Arab, although Jews were always there. The Ottoman Empire turned over Palestine to British rule after WWI, and the British encouraged Jews to return to their ancient homeland. Jews immigrated there in such massive numbers, buying up the best land, that by World War II, the Jews were nearly equal in number to Arabs. Palestinians deeply resented this, which they saw as an invasion of their homeland. After the Nazi holocaust of World War II, many more Jews fled to Palestine. Britain tried to divide the nation between the Palestinian Arabs and the Jews. Israel agreed to the two states solution, but the Arabs refused, only wanting the eradication of the Jews. This led to war, which the Jews won, establishing the state of Israel in 1948. Feeling disenfranchised, Palestinians have resorted to riots and terrorism ever since then. Israel has consistently won wars with the Arabs, and has often made peace with Arab neighbors by returning land in exchange for peace, especially with Egypt. However, Arabs living in Gaza (the “Palestinians”) and West Bank, have refused to make peace.

This is only a simplified summary of the Middle East. There are many other pieces to the puzzle, and other complicating factors. But if you understand these four key pieces above, you will have a much clearer picture of the Middle East puzzle.

(Dr. Bob Rogers has a Th.D. in Church History, and has taught History of the Middle East at The Baptist University of Florida.)

Book review: A novel of women surviving ISIS

“Today is Nazo Heydo’s wedding. The day she will set herself on fire.”

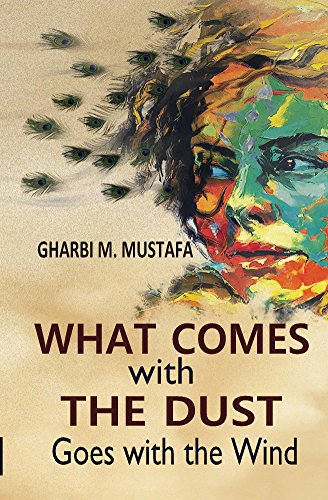

Thus begins What Comes with the Dust: Goes with the Wind, Gharbi Mustafa’s gripping novel about women who survive the abuses of the Islamic State.

I have read Gharbi Mustafa’s first novel, When Mountains Weep, which is the story of a Kurdish boy coming of age when Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein tried to exterminate the Kurds. I knew Mustafa was as excellent novelist, so I was looking forward to this second novel about the suffering of Yazidi Kurds under ISIS. I was totally blown away by this new book. Mustafa’s first book was very good; this book is great.

What Comes with the Dust: Goes with the Wind is a long title, which comes from the Yazidi religious legends that are explained in the book. It is a story about two Yazidi women, Nazo and Soz, and their struggle to survive. Nazo must escape slavery from ISIS to reach her forbidden lover. Soz is a female soldier who fights ISIS but also struggles with a secret love. Their fates are intertwined in a heart-wrenching story taken directly from the events we see on the daily news.

In 2014, the world watched in horror as Kurdish helicopters dropped relief supplies and tried to rescue thousands of Yazidis on Shingal Mountain in Iraqi Kurdistan, trapped there by ISIS. Since then, the United Nations has recognized the Yazidis re the targets of genocide by the Islamic State.

Who are these Yazidis? Why are the Kurds so eager to rescue them? Why is ISIS so eager to destroy them? This novel answers these questions, even though it is a work of fiction. In story form, the novel unravels the mysteries of the Middle East to western readers. Along the way, Mustafa shows us the mysterious religion and culture of the Yazidis, and contrasts these peaceful people with the fanatical cruelty of ISIS. Rich in culture and characters, and jarring in its account of jihadist brutality, it is a story that keeps the reader turning the pages to the end. I simply could not put it down until I finished.

Gharbi Mustafa is uniquely qualified to write this story. A Kurd himself, Mustafa is professor of English at the University of Dohuk in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. He has personally interviewed Yazidi women who escaped ISIS, and knows the culture like few writers in the English language. As a novelist, he writes in a way that is at once deeply moving and enlightening. It is well worth the two hours and 200 pages.