Breaking Barriers: The story of the first Black students at a Mississippi Baptist college

Copyright by Robert C. Rogers

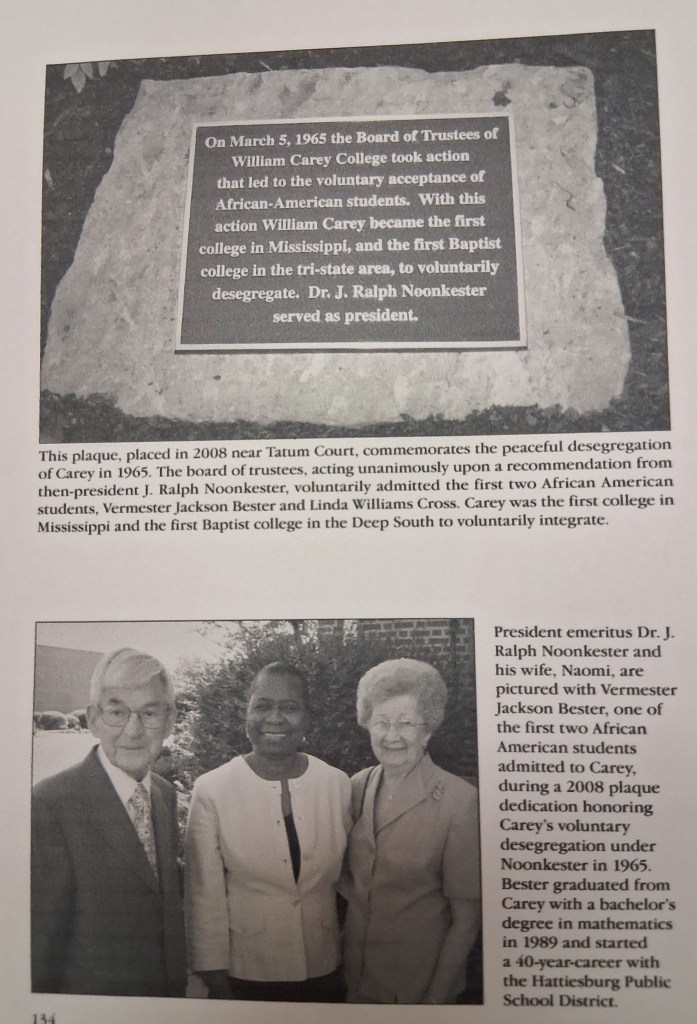

On March 5, 1965, the trustees of William Carey College (now William Carey University) voted to comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, promising not to discriminate based on “race, color, or national origin.” Thus, the Baptist college became the first Southern Baptist institution in Mississippi to racially integrate.

Carey’s president, Dr. J. Ralph Noonkester, contacted the principal of Hattiesburg’s Rowan High School to recruit the first Black students. The principal spoke to the parents of Linda Williams and Vermester Jackson, two honors graduates, and their parents approached each young lady about the possibility of becoming the first Black students at Carey.

Neither Linda nor Vermester had considered the possibility. Although her own grandmother had been a housekeeper at the college for years, it never occurred to Linda that she would be a student there. Linda responded to her parents, “We go where?” She had planned to go to Mississippi Valley State, a historically Black college where she had friends.

Vermester already had a scholarship to Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois, when her parents approached her about going to college at Carey. “My mother said, there are lots of kids who can’t go anywhere with a scholarship like you can,” implying that she could break the color barrier for other students if she went to Carey. “We decided to do it.”

“We had no idea what danger we were in,” said Linda. Unknown to either girl, the night before their first day at school, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on the lawn of President Noonkester. That night, Black residents in their neighborhood slept with shotguns by their beds, something Vermester’s parents only told her later. Linda said, “My Dad was apprehensive; he feared a firebombing of our yard.”

Linda and Vermester lived near the campus, on opposite ends of Royal Street. Linda said, “I lived on the west end, and she lived on the east end of the street, so we met up at Tuscan Avenue and we both walked to school.” Vermester remembered smelling something, but didn’t know about the cross-burning, as it had been cleaned up. As they walked up to Tatum Court on the Carey campus, Linda asked her, “Girl, are you scared?” Right then, they saw a Black maid cleaning the stairs, who said, “We’re watching out for y’all.” The maid was right. In fact, Linda says, “We had five young Christian women [students] who met us on campus and led us around to show us our buildings. It was very comforting to know we didn’t have to do it alone. That made the transition pretty easy.” Vermester added, “That first day, every time I turned around, I could see Dr. Noonkester. He would stop and ask how things were going.”

At the same time, their friend Gwendolyn Elaine Armstrong was one of two Black students integrating Hattiesburg’s other college, Southern Miss. Armstrong and the other Black students at Southern Miss had to have protection from the National Guard, and she told Vermester that students were spitting on them. “But we didn’t have any group that showed hatred or disapproval,” said Linda. “I remember some heckling,” she added, but compared to their high school classmates’ experience at Southern Miss, they would say to each other, “Girl, we’re blessed.”

Vermester was a math and English major, and Linda was a business major, so they only had one or two classes together, including an English composition class. When they walked into that classroom, a young man got up and left. Years later, Linda met the same man when he came to pay his bill at Mississippi Power Company where she was working. Recognizing her, he apologized. Another memory both Linda and Vermester had of that class together was how their teacher pronounced the word “Negro” in a short story she was reading, so it sounded more like the N-word.

Despite having few classes together, both girls studied hard and were encouraged by the faculty to join organizations and get involved. Their greatest encouragement, however, came from their families and the Black community. Their parents made sacrifices for them, such as relieving them of chores, so they could study. Neighbors would ask, “Do you need any help?” The second semester some Black students transferred in from Prentiss Institute and Mississippi Valley State, making at least five Black students on campus. The following year, Black enrollment increased a good bit, and some of their classmates from Rowan High School came.

Their junior year, Linda transferred to Mississippi Valley State “to experience dorm life,” but she decided she wasn’t going to let Vermester walk across the stage at graduation by herself, so she returned to Carey for graduation. By the time they graduated in 1969, there were photographs of 76 Black students in the Carey yearbook. They were from all of Mississippi, but most were from Hattiesburg.

After college, Linda and Vermester went separate ways. Vermester married Mr. Bester and taught math in the Hattiesburg Public Schools, retiring from Hattiesburg High School. She never talked about being one of the first Black students at William Carey University. She said, “For the longest time, it didn’t occur to me what Linda and I had done.” Other people talked about it, though. “I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘If it hadn’t been for you and Linda, I wouldn’t have been able to go to school.’ It warms my heart.” She is proud to say that her grandson, Cory Bester, graduated from Carey.

Linda eventually moved out of state, living many years in Minnesota before retiring in Pensacola, Florida, where she resides today. “I’ve had men and women tell us, if you had not done this, we would not have gotten our degrees. I had a young lady I babysat, who later got her doctorate there. I have a niece and a nephew who went to Carey,” says Linda. Two scholarships to William Carey University have been established in their names, one a partial scholarship and the other a full scholarship.

However, Linda did not receive her own diploma. A mix-up over her transfer to Valley State and back to Carey somehow caused her to miss 3 hours credit that she thought she had when she walked across the graduation stage in 1969. Back then, they would mail the real diploma after graduation, but she never received it. In 2024, she and her son were on the Carey campus and met the current president, Dr. Ben Burnett. When they explained what happened, he said, “We’re going to fix that.” On May 10, 2024, Linda Williams was the last person to walk across the stage of the graduation ceremony at William Carey University, and she received her diploma at last. “They gave me two standing ovations. It was like I was graduating all over again! It was so surreal. Dr. Noonkester’s son, Myron, had the honor of giving me the diploma his Dad would have given me,” said Linda. Linda thought of her grandmother, who was a housekeeper at the college when it was known as Mississippi Woman’s College. “She would have loved to have seen that happen to me.”

Vermester says, “What I treasure most is that William Carey College lived up to the Christian spirit. Somehow, they managed to make it happen, in a way that benefitted us and our community.”

SOURCES: Linda Williams, telephone interview by author, February 7, 2026; Vermester Jackson Bester, in-person interview by author, February 4, 2026; Robert C. Rogers, Mississippi Baptists: A History of Southern Baptists in the Magnolia State (Mississippi Baptist Convention Board, 2025), 224-225.

Discover more from Bob Rogers

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Posted on February 10, 2026, in Christian Living, history, Mississippi, Southern Baptists and tagged civil rights, faith, Hattiesburg, history, integration, J. Ralph Noonkester, Linda Williams, Mississippi, Mississippi Baptist Convention, racism, segregation, Southern Baptists, Vermester Jackson, Vermester Jackson Bester, William Carey College, William Carey University. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0